Jo Shishido (1933-2020)

January 21, 2020 · 0 comments

Jo Shishido, who died yesterday in Tokyo, will be remembered as the charismatic moon-faced star of many a Nikkatsu Action film from the 1960s. He is best-known in the West for his iconic turn as the cold-hearted contract killer of Seijun Suzuki’s cult classic Branded to Kill (1967).

Shishido’s lead role as the neatly turned out Hanada, who gets turned on by the scent of boiling rice as he fights for number one position in the hierarchy of hired hitmen in the Tokyo underworld saw him firmly identified as the face of the legendary director, who passed away just two years before him.

With his trademark cheeks, bolstered by collagen implants to enhance his onscreen presence, his deep booming voice and the subtle suggestion of an awareness of the ludicrousness of many of the films he appeared in always playing upon his lips, Shishido provided the perfect foil for the eccentric pop art excesses created by Suzuki at Nikkatsu. Neverthless, his roles for the director were surprisingly few. Despite supporting parts in the early Suzuki works The Naked Woman and the Gun (1957) and The Boy Who Came Back (1958), playing the young punk who attempts to drive the film’s star Akira Kobayashi back off the rails as he tries to go straight after his release from reform school, Shishido’s first significant appearance for Suzuki was in the gleefully titled Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! (1963), a flamboyant crime caper adapted from a series of pulp novels by Haruhiko Oyabu.

With his trademark cheeks, bolstered by collagen implants to enhance his onscreen presence, his deep booming voice and the subtle suggestion of an awareness of the ludicrousness of many of the films he appeared in always playing upon his lips, Shishido provided the perfect foil for the eccentric pop art excesses created by Suzuki at Nikkatsu. Neverthless, his roles for the director were surprisingly few. Despite supporting parts in the early Suzuki works The Naked Woman and the Gun (1957) and The Boy Who Came Back (1958), playing the young punk who attempts to drive the film’s star Akira Kobayashi back off the rails as he tries to go straight after his release from reform school, Shishido’s first significant appearance for Suzuki was in the gleefully titled Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards! (1963), a flamboyant crime caper adapted from a series of pulp novels by Haruhiko Oyabu.

He was back with Suzuki but a few months later in Youth of the Beast (1963), a work equally colourful but much more darker in tone, playing the renegade ex-cop who goes undercover amongst two rival yakuza gangs to investigate the murder of a colleague. It was the film that put Suzuki on the map as far as the local critical establishment were concerned. Shishido’s brand of boorish, bull-headed (and faintly ridiculous) exaggerated machismo and boyish petulance provided the very essence of toxic masculinity in his role as the black marketeer on the run from the Occupation forces after murdering a G.I. in Gate of Flesh (1964), whose presence threatens to disrupt the fragile solidarity of the group of four prostitutes sheltering him, who have found their own strategy of coping in the shattered ruins of post-war Tokyo.

Shishido’s third major role for Suzuki in a period of little over a year was to be his last for the director until Branded to Kill, although one assumes diktats from the powers-that-be at Nikkatsu played some part in keeping the pair apart. The familiarity of Shishido’s moon-face with Western fans of Japanese cinema must largely be attributed to the elevated profile of Suzuki abroad compared with other directors at the studio, because even around the time of this brief run of collaborations, the shine had long gone off this particular member of the select ‘Diamond Guy’ leading men promoted by the studio.

Born in Osaka in 1933, Shishido entered Nikkatsu after passing its first New Faces audition in 1954, making his debut that same year, albeit far down the cast list, in Police Diary (1955), directed by Seiji Hisamatsu. And far down the cast list he remained for his first few years too, usually playing hoods and heavies, until plastic surgery on his cheeks in 1957 changed his fortunes and a unique and characteristic screen presence came to the fore.

Coarse, boorish, explosively unpredictable but with mischievous self-awareness that almost crosses the line into pure ham, Shishido came to specialise in lovable rogues. He was initially pitted as onscreen rival to his fellow contracted star, Akira Kobayashi, in a string of titles including the first instalments of the long-running Rambling Guitarist (1959-62) series. These films typified the ‘mukoseki action’, or ‘Borderless Action’ brand that Nikkatsu studios began pushing at this point, with star-driven entertainment films hybridised from internationally-popular cinematic genres like Westerns, comedies and detective movies with no particularly tangible Japanese aspects to them. It was in such works that Shishido assumed his first onscreen persona of “Hitman Joe”. He was literally branded to kill.

Another piece of studio branding in 1961 came with the creation of the Nikkatsu’s Diamond Guys line of leading men, with the company’s conveyor-belt levels of production resulting in a string of higher-profile works constructed and marketed around the personalities of contracted stars like Yujirô Ishihara, Akira Kobayashi and Hideaki Nitani. Shishido was paired up with the latter for Dirty Work (1961), a comic buddy movie in which his rakish cocksure screen persona was tempered by that of Nitani’s altogether more velvety charm.

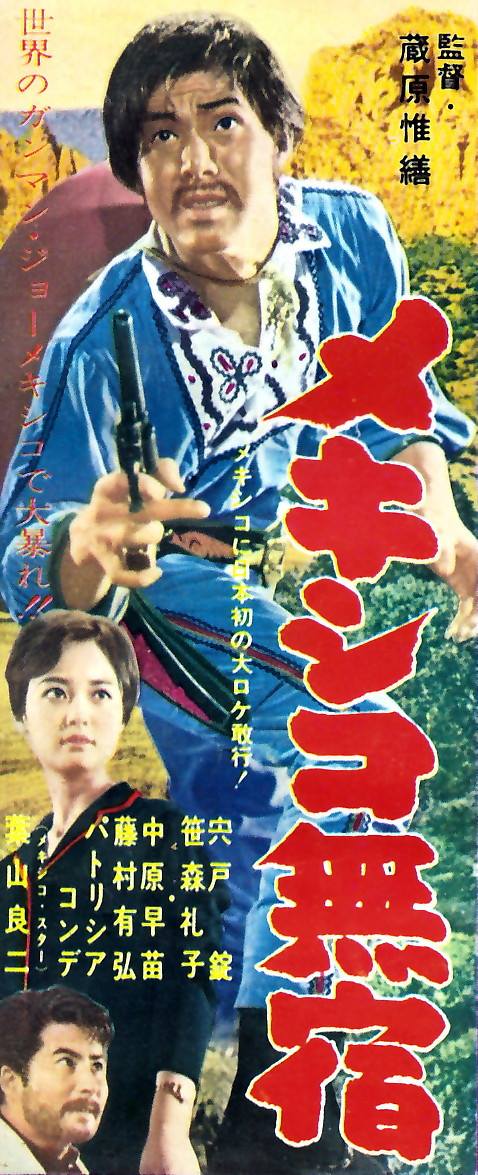

That peculiar genre of the Sukiyaki Western saw Shishido’s transformation from “Hitman Joe” to “Joe the Ace”, in such bizarre confections as Takash Nomura’s Fast-Draw Guy (1961), Akinori Matsuo’s Gun of the Northern Railroad (1961) and Koreyoshi Kurahara’s Mexico Wanderer (Mekishiko mushuku, 1962), one of Nikkatsu’s first productions shot on location overseas, while later taking his battles with Nitani across the seas in the Tan Iida swashbuckler Pirate Ship: Tiger of the Sea (1964). The “Joe the Ace” moniker fit well with Shishido’s louche appeal, with his characters often seen lolling around shady bars and nightclubs in their downtime, cradling a whiskey in one hand and a deck of cards in the other.

That peculiar genre of the Sukiyaki Western saw Shishido’s transformation from “Hitman Joe” to “Joe the Ace”, in such bizarre confections as Takash Nomura’s Fast-Draw Guy (1961), Akinori Matsuo’s Gun of the Northern Railroad (1961) and Koreyoshi Kurahara’s Mexico Wanderer (Mekishiko mushuku, 1962), one of Nikkatsu’s first productions shot on location overseas, while later taking his battles with Nitani across the seas in the Tan Iida swashbuckler Pirate Ship: Tiger of the Sea (1964). The “Joe the Ace” moniker fit well with Shishido’s louche appeal, with his characters often seen lolling around shady bars and nightclubs in their downtime, cradling a whiskey in one hand and a deck of cards in the other.

Alas, as the Japanese film industry’s fortunes began to falter in the mid-1960s, it was not long before Nikkatsu began refocussing its attention elsewhere, and Shishido, along with fellow Diamond Guys Nitani and Kobayashi, found themselves side-lined. It was back to bad guy roles, playing against ‘new face’ Tetsuya Watari in Toshio Masuda’s Velvet Hustler (1967), or lower-budgeted potboilers like Nomura Takashi’s astonishing hard-boiled ‘Nikkatsu Noir’ A Colt Is My Passport (1967), in which Shishido was one of a pair of hitmen on the run lying low in Yokohama while waiting for their ship to come in to take them to safety.

Shishido left shortly after Suzuki’s studio swansong with Branded to Kill saw him fired, but not before his parting shot in Yasuharu Hasebe’s brutal portent of gangster films to come with Retaliation (1968), in which the actor stood alongside a number of his fellow former screen idols from Nikkatsu in a depiction of a destructive internecine war between rival yakuza gangs that might be viewed as reflecting the internal turmoil between the creative talent and the management of the studio itself. Neither was Shishido alone amongst other stars of the sixties popping up in the new landscape of the jitsuroku “documentary-style” yakuza film of the next decade, putting in a sterling performance as the aged gang boss fiercely protective of the gangland code of honour in the final part of Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles with Honour and Humanity in 1974.

Shishido also came back in Suzuki’s failed comeback attempt, A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness (1977) and he did a turn as Osamu Tezuka’s manga hero Black Jack in Nobuhiko Obayashi’s The Visitor in the Eye (1977). However, like most of his generation of movie stars, he spent much of the decade on television, appearing to a new generation in Tsuburaya Productions sci-fi series Star Wolf (1978) as Captain Joe (episodes of which were edited into a standalone feature for American TV as Fugitive Alien in 1988). In foreign movie-dubbing, he would provide the voices of Burt Reynolds, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland.

He returned to the big screen on a number of occasions, including guest appearances in all three of Kaizo Hayashi’s ‘Yokohama Mike’ trilogy of film noir homages that began with The Most Terrible Time in My Life (1993), and in Takashi Ishii’s glossy erotic thriller Flower & Snake II (2006), about which the actor joked of adding “Dirty Joe” to his evolving list of screen personas.

Shishido’s wife Yuko Shishido passed away in April 2010, aged 77, while the actor hit the headlines in 2013 when his house was destroyed in a fire. Fortunately he was not at home at the time, although many of his possession and memorabilia accumulated across sixty years on screen and stage were lost. He leaves behind a body of work consisting of well over 250 film appearances.

Leave a Reply