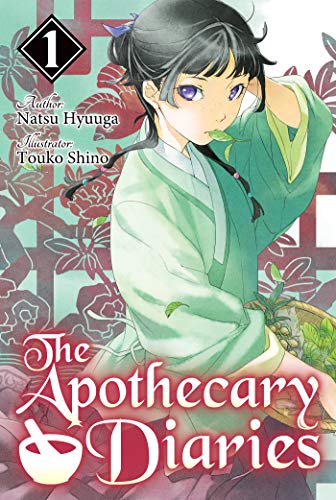

Books: The Apothecary Diaries

March 7, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

It is the ultimate in blood-sports – hundreds of the most beautiful women in the world, locked away in a palace where their sole chance of advancement is to catch the eye and bear the heir of the Emperor. Throw in scheming eunuchs, bitter sister-wife rivalries, and the ever-present danger that years of careful seduction will be ruined by the next young dollymop to sashay across the threshold, and it’s a heady mix of teen drama and intrigue.

Maomao, however, has a hidden talent. Before she was abducted and sold into what we might as well call slavery, she was an apothecary’s daughter. This gives her a rare skill in the ever-paranoid harem – a knowledge of the uses and abuses of herbs and poisons. Amid much skulduggery among the women of the palace, Maomao is appointed poison taster to Consort Gyokuyou. None of the other ladies-in-waiting really appreciate what this means; they regard Maomao as a pathetic and disposable pawn, whose sole duty is to die in her lady’s place if someone slips some arsenic in her porridge. But Maomao has a long history with poisons – her arms are riddled with pockmarks and scars from experimental skin tests and snake-bites, and she has a forensic grasp of how poisoning works. From the moment she suggests that Gyokuyou eats off silver plates, which would be visibly discoloured by certain toxins, she proves her worth to her new mistress.

I first heard about The Apothecary Diaries when a colleague asked me how historically accurate it was. It was hence something of a disappointment to discover that it isn’t “accurate” at all, being set in an unspecified fantasy realm that happens to look a bit Chinese. Asides referring to New World foods, including cacao and the potato, suggest that this is supposed to be the late Ming or early Qing dynasty, but there are no real indicators of time or place. China has had poison tasters since the Bronze Age, and inner-palace intrigues for more than two thousand years. Author Natsu Hyuuga might say this is set in a “fictional realm”, but she could just as easily have called it Yanxi Palace or Empress Wu fan fiction. However, that’s not all that unusual in publishing, where oft-times writers will spare both readers and themselves from the inconvenience of due diligence by setting everything in an imprecise dream-time. The most memorable example of this in Japan was Like a Cloud, Like a Breeze, another tale of harem intrigues that won a literary competition in 1989, the prize for which was to be turned into an anime TV movie. That, too, turned out to be as realistically Chinese as chop suey.

But Imperial China, even if presented with hand-waving vagueness, is an irresistible topic for a novelist. The tense intrigues of heirs and favourites, and the brutal one-upmanship of wives and concubines, takes the idea of high-school frenemies to a whole new level. Maomao is a self-harming teenage wallflower in an institution populated solely by other girls who will literally kill each other over the chance to go to the prom. In that most imperial of Bechdel tests, there is only one man who matters in the whole world, and the women talk about him all the time, but he is literally the master of all he surveys, and anyone who can snare his heart and bear his favourite son and stay alive will be the queen bee.

There’s also a strong element of Cinderella rags-to-riches. A lowly underling in the inner palace, Maomao starts out sleeping in a crowded dorm, and eating gruel in a grim refectory. She yearns, with a passion that will be familiar to anyone trapped in a pandemic lockdown, for simple treats like kebabs from the street market – a freedom denied her since she was walled away from the outside world. There’s little discussion, at least not in this book, of Maomao’s chances for being an imperial concubine herself – she is much more interested in clambering up the ranks of the servants to better quarters and pay, all the better to somehow escape from the palace.

Food is a recurring theme in The Apothecary Diaries. Different dishes can represent nostalgia for the meals of Maomao’s lost home life, or markers for the feasts and celebrations of the palace. Once Maomao’s mastery of herbs and chemicals becomes known, her career path shifts again, as she is approached by nervy girls in search of poultices, tonics and love potions. As in the real China, the line between food and medicine (and drugs, and even dyes) can get very blurred, but it is where Maomao is most at home. The result is an odd recipe for drama, somehow combining an episode of Nigella Bites with a daily game of Russian roulette, in a Big Brother house populated entirely by feuding supermodels.

Jonathan Clements is the author of The Emperor’s Feast: A History of China in Twelve Meals.

The Apothecary Diaries is available from J-Novel Club.

Leave a Reply