Books: Eavesdropping on the Emperor

April 17, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

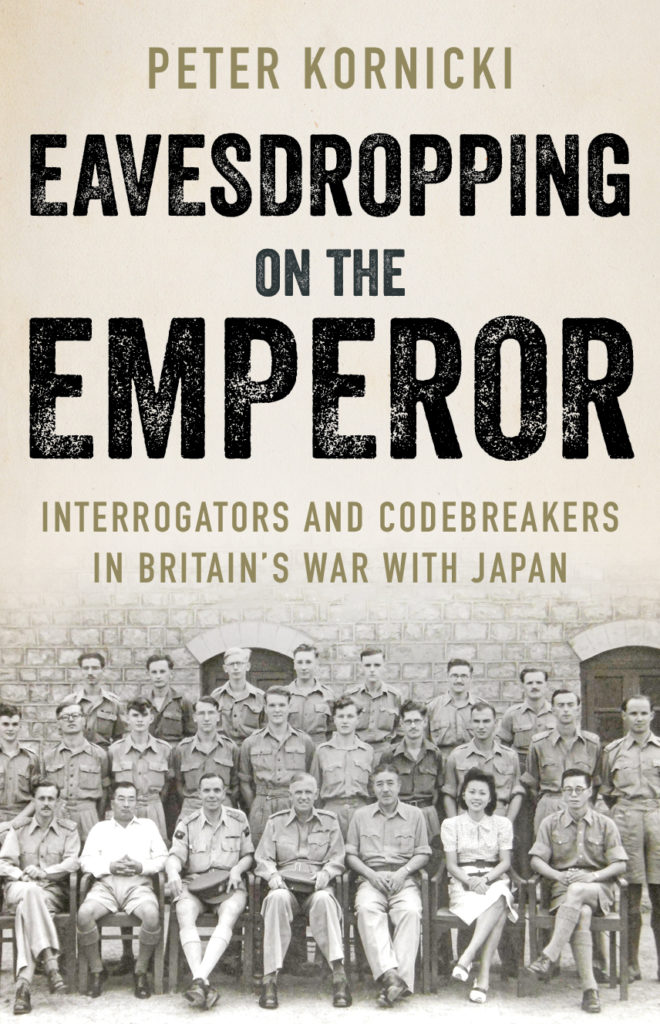

In 1939, Japanese embassy personnel in London were ordered to destroy stacks of compromising documents, and made the mistake of hiring a local company called Tottenham Dust Destroyers. Explicitly told to burn crates full of books and papers and not to tell the police, the Dust Destroyers immediately did so, alerting MI5 to the possibility that the Japanese might be Up to Something. This tale of Tottenham trash collectors is but one of the charming asides in Peter Kornicki’s book Eavesdropping on the Emperor: Interrogators and Codebreakers in Britain’s War with Japan, which details the fall-out from the declaration of a war against a country with a language that almost nobody in Britain spoke.

In the first 23 years of its operation, the institution then known as the London School of Oriental Studies (today’s SOAS) only produced two graduates in Japanese. This was despite repeated pressure from policy wonks like one Colonel Grimsdale, begging the establishment to have a ready supply of linguists to hand in case of any trouble in the East. The problem was, Grimsdale noted, “a number of chaps just can’t take these languages, and either take to drink or go a bit potty.” It is not the last time that Kornicki wryly recounts the sheer disbelief of the authorities when it came to the difficulties of finding anyone crazy enough to want to learn Japanese.

Many of the programmes that hot-housed these linguists were classified until the 1990s, and as Kornicki gleefully discovers, some of them still are, with archivists refusing to let him see certain papers until a 2029 cut-off point. He tracks down some of the last survivors of the secret programmes, and uses their memoirs and sometimes even memorabilia to fill in gaps and work out who was where and when. It’s not the first time that Kornicki has written in a somewhat more populist mode than his academic work, and here he takes evident pleasure in retelling the life stories of the many nutters, eccentrics and, yes, future professors, who ended cramming a language under wartime conditions so they could eavesdrop on radio transmissions, crack codes, and make it possible for both sides to talk to one another in war and peace.

Despite a few pre-emptive language schemes, it was not until the aftermath of Pearl Harbor that Allied authorities tardily started casting around for officers who can listen to Japanese radio transmissions, translate Japan’s unique form of Morse Code, and assist in interrogation and administration. Kornicki’s lively account deals with the relentless drilling of unsuspecting recruits, subjected to ruthlessly regimented secret classes from which a weekly grade below 80% meant instant expulsion. “After the first two weeks,” he writes of one US Navy language school, “all their conversations over lunch had to be in Japanese, and one of their teachers was at the table with them to make sure the rule was obeyed.” And yes, the international nature of the Allies means that this initially British tale does wash up in far-flung corners of the world, with students dispatched to the United States and Australia, where one Melbourne landlady found books of strange squiggles in her lodger’s room, and reported him to the police, until she was assured that he was learning Japanese out of patriotism, not treachery.

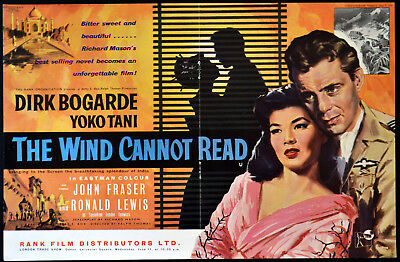

Richard Mason, who would find greater fame later in life with The World of Suzie Wong, wrote an earlier novel about a romance between a language officer and the Japanese woman who is supposed to be training him, thought to be inspired by his own training as an interpreter-interrogator. In The Wind Cannot Read, later adapted into a film starring Dirk Bogarde, his protagonist is told: “Only the best brains can learn Japanese. It requires a reorientation of the mind. You think backwards and write upside-down.”

Recruitment for the British languages programme led to a number of prospective candidates being rounded up and dragged off for a bizarre interview in which they were quizzed on their interests in chess, the speed with which they could complete a Times crossword and, bafflingly, their taste in music. Sadly, Kornicki does not reveal what the preferred answer might be to this last one. He does, however, uncover the long and bitter spats between the military and academia, as officers demand that professors knock up a language course to teach Japanese to an advanced level in an impossibly short time, compressing a timescale of up to seven years into mere months.

The military found a way through, concentrating on an extremely limited vocabulary purely of the sort of terms liable to crop up in radio transmissions, compressing the necessary time to just eleven weeks… although as the director of one such experimental course at what is now GCHQ confessed, after five weeks, a number of the students were “carried away screaming.”

Kornicki presents an ever-changing carnival of characters on both sides, including the Japanese boffins who try to fox eavesdroppers by employing code-talkers speaking in the unintelligible Kagoshima dialect, and the conveniently chatty Japanese attaché in Berlin, one General Oshima, whose communiqués back to Tokyo presented the British with a treasure trove of handy intelligence. One wonders why some enterprising film producer hasn’t already latched onto the tale of two American-born Japanese, who even attended the same school in Kumamoto, one of whom remained in Japan, the other of whom enlisted in the US Army, both of whom found themselves on opposite sides of the surrender negotiations in 1945.

And as one of Kornicki’s characters gratefully discovers on Mindanao in the Philippines, a hefty Kenkyusha Japanese dictionary is also thick enough to stop a bullet.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Japan at War in the Pacific. Eavesdropping on the Emperor, by Peter Kornicki, is published by Hurst.

Leave a Reply