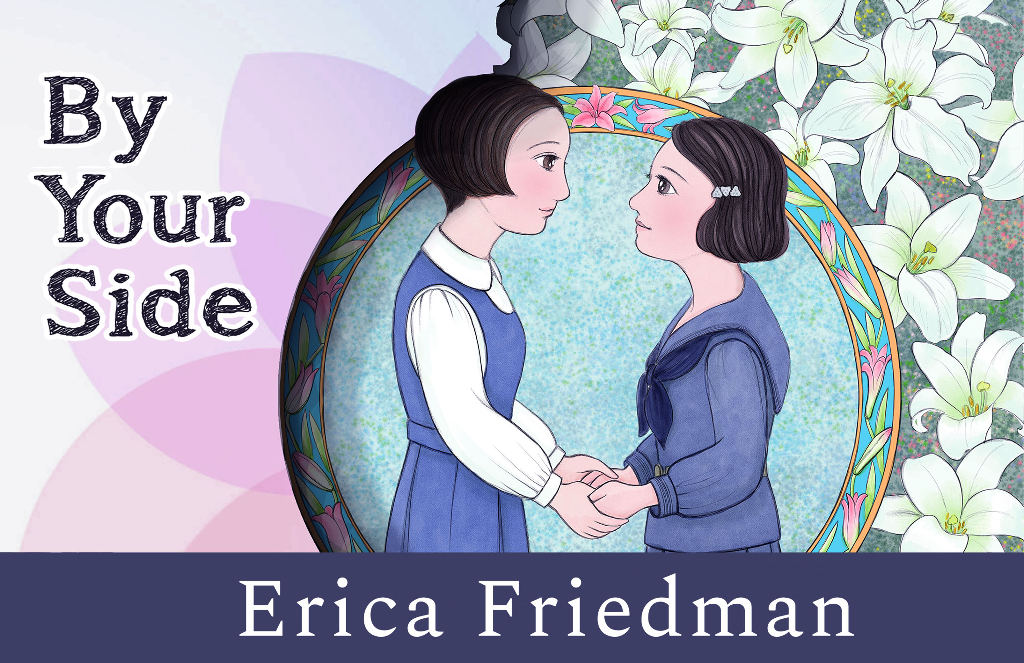

Books: By Your Side

June 22, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

The inauguration of Barazoku (“Rose Tribe”), a magazine for gay men in 1971, brought with it a sop to the ladies, in the form of a page for lesbians, for which author Ito Bungaku coined the term yuri-zoku, the “Lily Tribe.” Ever since, lesbian media have officially been a thing in Japan, although as Erica Friedman points out in her new book By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and Manga, they were around long, long before then, and did not truly flourish until a generation afterwards.

Friedman has spent the last twenty years writing a blog on yuri, from which the chapters of this book have been drawn. She preserves some of the variations in tone and editing as a mark of changing attitudes, or so she claims – one suspects that a more mainstream publisher might have pushed her to write a more cohesive single narrative than a collection of long articles that occasionally repeat themselves, but then again, a mainstream publisher probably wouldn’t have published this book at all. Fortunately, the origin of this book as disparate essays and speeches does not detract from its overall usefulness, and Friedman’s opening comments to the chapters help frame them in their original context – this one mounted a specific argument at Anime Feminist; that one was designed to introduce LGBT subjects to a crowd of manga fans at a convention; this one was the opening of yuri strands at a Mechademia conference etc.

A significant part of her narrative is taken up with a prehistory of yuri, which is to say those decades in which lesbian content was either discreetly obscured or the product of readers’ and audience’s subversive wish-fulfilment – as well as titles like Girl Revolution Utena, Maria-sama is Watching, and, believe it or not, Bodacious Space Pirates that could be seen as lesbian if you squinted at them a certain way. But as Friedman persuasively argues, unlike many other manga genres, yuri “is not dependent on the target audience for definition…. The girl prince, the wide-eyed little sister, the hyper-competent older sister, the motorcycle-riding predatory lesbian, schoolgirls in love, office ladies confused by their feelings for a co-worker, lesbians left behind by their lover who went off to be married, women making a life together – all have an equal place…” And it’s true, although the far right may clutch their pearls in horror at the possibility of all that gay-agenda propaganda, the stories in, say, Yurihime magazine are wonderfully inclusive and wide-ranging.

She starts off with the first stirrings of media for homosexual readers, including the “S” themes of early twentieth century – a love that dare not speak its name, so much so that nobody can agree what “S” stands for. It might be “sisters” or “Sapphic” or even something else. Refreshingly, she does not treat manga in a vacuum, acknowledging that the first crucial influences in the genre came from prose novels like Nobuko Yoshiya’s Two Virgins in the Attic (1919), in which the simple quest even for “a room of one’s own” becomes a political, revolutionary gesture for women of the era. She also notes the long-term influence of Maid of the Harbour (1938), once credited to Yasunari Kawabata, but increasingly regarded as the work of his “assistant” Tsuneko Nakazato, which is either a light-hearted tale of high-school crushes, or a sordid allegory of forbidden love, depending on whom you ask.

It’s only in her eighth chapter that the genre breaks out of small-press lesbian magazines or nudge-nudge asides in the mainstream, and becomes a demonstrable market sector of its own. Even then, there is soon a split, with even Yurihime dividing into its original format, in which girls continued to be in love with girls, and the spin-off Yurihime S, in which lesbian affairs were presented specifically for the titillation of male readers. This soon leads to the bizarre situation in which, in the words of Sarah Frederick, critics are advised to watch out for the minefield of assuming an author is lesbian (or not), that her characters are lesbian (or not), or that the story in which they appear is lesbian (or not) – “the irony of not acknowledging a lesbian’s lesbian work as lesbian.”

There is an additional issue as well, which Friedman politely does not mention, so I will go ahead here – the works of two of the most influential female manga creators in Japanese comics history are riddled with same-sex themes and discussions, progressive dialogues and situations. Their biographies even hint at the possibility that they were once in a relationship with each other, which would make them, in a sense, the most influential power-couple in manga history, outclassing even the husband-and-wife celebrity of Kenshi Hirokane and Fumi Saimon, or Hideaki and Moyoco Anno. However, they have never, to my knowledge, openly proclaimed their sexuality, nor are they under any obligation to do so. So, even though their media profiles are loaded with hints, the community of manga critics is obliged to say nothing until the moment that the creators choose to out themselves. On the day that they do, the ability of the LGBT lobby to claim them as their own will be so game-changing that it may rewrite the entire history of Japanese comics. Until then, it’s nobody’s business but theirs, which must be fist-gnawingly annoying for the yuri manga lobby!

Friedman is keen to stress that it is perfectly feasible for yuri to embrace platonic friendships without sexual content. Or to put it in terms that have dogged Doctor Who for the last decade, the “gay agenda” doesn’t need to be super-gay. Who’s once and future showrunner, Russell T. Davies, in fact, introduced me to a useful term in modern criticism – the “heterosexuality” of mainstream drama, in which is it assumed that if a woman and a man are onscreen together, there needs to be some acknowledgement of chemistry (or lack of it) between them. In other words, it’s Chekhov’s Gonads, and if people have got them, popular tradition demands that they must be used. Adrienne Rich, whose 1980 comments on “compulsory heterosexuality” seem to be the origin of much of this, also talks of a “lesbian continuum”, and although she is unmentioned here, Friedman’s book forms an argument that yuri can occur at any point along it.

And so, much as one anonymous producer once badgered Aaron Sorkin that there was “no point” to Demi Moore being a woman in A Few Good Men if she wasn’t going to bang Tom Cruise, just because two women are good friends, or love each other, or live together, and just because their story is drawn by a woman who might like women herself, Friedman points out that calling it a “lesbian” manga brings a whole bunch of political or narrative assumptions that are not necessarily productive or illustrative.

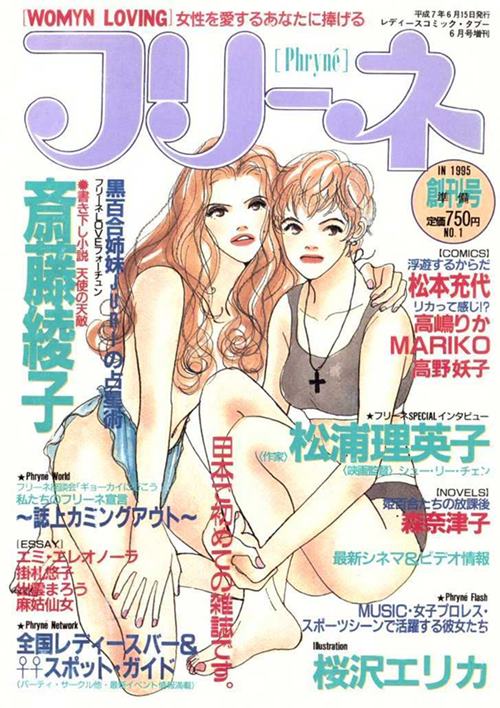

Perhaps deliberately covering different ground to Deborah Shamoon’s Passionate Friendship, Friedman, takes us through the early “S” allusions in mainstream manga, such as Ryouko Yamagishi’s Our White Room in 1971, and the short-lived Phryné, a fascinating-looking magazine that lasted for just two influential issues in 1995. She examines the stereotypes of lesbian manga, its girl princes and closeted-heteros, scoffing at the interminable “Story A” that has been the basic template for decades: “There is a girl; she likes another girl. The other girl likes her. They like each other. The end.” She devotes a particular screed to what, in her mind, is the worst of all tropes, the mentally-unhinged lesbian, not the least because until 1995, when homosexuality ceased to be described as a mental illness in Japan, it was a legal tautology. Another chapter deals with the power politics in lesbian relationships as depicted in manga, contrasting them with the older-younger, dark-light divisions of manga for gays.

Friedman closes with a series of thematic chapters, discussing some of the classics of yuri story-telling, but also associated issues like a timeline of yuri fandom in the United States – a phenomenon in which she has been instrumental. She examines new trends arising in yuri in the 21st century, including “alternative families” and the degree to which “living happily ever after” is a possibility in the real world, or just a thing we read about in fairy tales.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Erica Friedman’s By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and Manga is published by Journey Press.

Leave a Reply