Her Blue Sky

October 18, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Akane (Riho Yoshioka) is a small-town lady in rural Chichibu, surrogate parent to her teenage sister Aoi (Shion Wakayama), and an enthusiastic part of the local community. And somehow she’s been drafted into a local publicity initiative to bring in a big lounge-singer star to jump-start the local tourist business. But this is not her story, at least not all the time. This is the story of other people in Akane’s life – the former schoolmates who went their separate ways after graduation; the sister who doesn’t see what Akane has done for her, and the boyfriend she ditched because of her family obligations. All are converging on Chichibu for a grand event that is fated to be a high-school reunion… and one of them is a living ghost.

The frog at the bottom of a well, so goes the Japanese proverb, doesn’t know the vastness of the ocean, but does know the blueness of the sky. In other words, and in a very Japanese sense of compromise, sometimes we have to make the best of where we find ourselves, even if our location, or situation, or companions were not what we first had in mind. It’s this sensibility that informs the original Japanese title of this film: To Those Who Know the Blueness of the Sky.

On the surface, Her Blue Sky initially looks like just another garage-band narrative, a bunch of kids coming together to ‘do the show right here.’ But from its opening scenes it is suffused with religious imagery, from the true-to-life glimpses of Buddhist iconography in Japanese architecture and daily life, to tiny touches like the image on the back of Aoi’s hoodie. Such acknowledgements even extend to the music, which swiftly shows its hand with a pop song inextricably linked in the Japanese mind to Buddhist history.

The band’s first performance is sure to put goose-bumps on the skin of Japanese (and British) viewers of a certain age. For old-timers like me, and anyone else who saw the NHK TV show Monkey on BBC re-runs or Blu-ray in the years since, the opening bars of Godiego’s “Gandhara” are unmistakeable, along with its doleful yearning for an unattainable utopia, tying it directly to the concerns of the film.

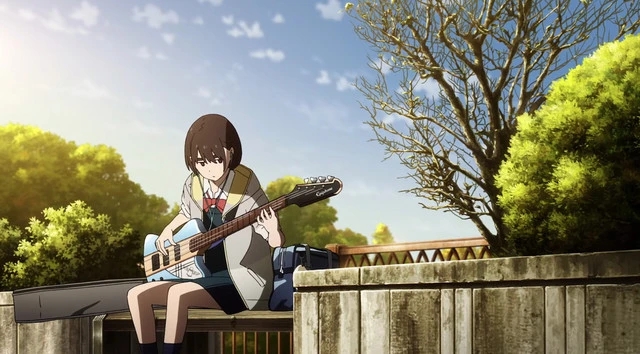

Understandably, part of the film’s presentation concentrates on sound, or its absence, as shown in an opening sequence when the teenage Aoi shuts out the outside world to practice with her bass on a bridge. Although she is in public, her headphones dispel the everyday bustle around her, much as personal stereos have done since the first pioneering days of the Walkman in 1979. When Akane and Aoi are suddenly orphaned, much of the dialogue in the funeral parlour is so muted that one needs to be watching with the subtitles on to know what is happening.

Fan-favourite scriptwriter Mari Okada returns, once again, to the setting of her home town of Chichibu, the subject of previous anime storylines in Anohana and Anthem of the Heart. She also returns to a common theme in her work – the compromises that people are forced to make by changes in their circumstances. Here, it’s the shattering of Akane’s teenage hopes to move to Tokyo in the vague hope of becoming a musician – instead, she gives up on her dreams, stays in her hometown, and tries to raise Aoi after their parents’ deaths. Fast-forward thirteen years, and Akane has a drab job at the town hall, Aoi is a resentful teen, and the small town is abuzz with the prospect of an A-list celebrity coming to perform in a local concert.

But it’s here that Okada introduces a real twist, riffing on her recurring consideration of the difficult decisions that people make in their lives. What if someone were haunted by their own past selves – an idea that dates back to the medieval Tale of Genji? What if, instead of accepting the situation that fate and their own life-choices throw at them, someone were split into the person they once were, and the person they have become? With an insight similar to that in her earlier Maquia: Where the Promised Flower Blooms, Okada offers a vision in which women are resilient, enduring towers of strength, and men are often broken by the pressures of the world. Nowhere is this more obvious than the scene in which a hysterical Aoi rails at Shinno, Akane’s high-school sweetheart. Akane has already gently informed Shinno that she will not be accompanying him to Tokyo, but Aoi reiterates this in an angry, screaming rant, while Akane cradles her impassively. Both of them are hurting, but Akane is refusing to show it.

As a grown-up a generation later, Akane remains brightly positive, effervescently popular with the townsfolk, telling Aoi that she shouldn’t worry about the long walk to school, because she can admire the autumn colours on the mountains. In a call-back to her own teenage years, Okada has the sullen Aoi proclaim that she “hates mountains” – a reference to the time when, asked to write an essay in praise of a local mountain, Okada wrote a polemic decrying it as an eyesore. Aoi thoughtlessly brags of how she is ready to quit her horrible hometown, unheeding of how much Akane has given up to stay there – again recalling Okada’s own account of her youthful antagonism towards her own mother, a subject dealt with at length in her memoirs.

Okada has fun with stereotypes and expectations. Aoi announces that she is going to Tokyo to become famous as a pop star, although she doesn’t actually have a band yet. It is presented as a daft, naïve decision, but then her classmate Ohtaki announces that she is going to get married, although she doesn’t yet know to whom. Both are ticked off as “employment decided” by a long-suffering careers officer. Meanwhile, Okada’s scenes juxtapose the concerns of grown-ups in today’s Chichibu with their more idealistic days as teenagers – it is much easier to feel for Masamichi, the portly, divorced civil servant who carries a torch for Akane, when we have already witnessed his hopeful, youthful heyday as a drummer in a rock band.

The plot revolves around that common theme in 2020s anime, “holy land tourism”, as town hall policy wonks bicker over the best way to attract tourists to their town. Potato-infused miso soup isn’t going to do it – they need a concert and a reason for people to drive over. Such deliberations would have been commonplace when the film was released in 2019, but today take on a new, more melancholy resonance, since Japan’s tourist industry remains dangerously deflated after two years of pandemic provisions. In fact, Okada’ storyline deftly marries many of the structural concerns of modern anime – tourist connections, music tie-ins, an aging audience – into a storyline as robustly suited to them as Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Gundam plots once pushed model kits.

Okada’s script is beautifully nuanced, poking gently at the anxieties and disappointments of rural life, as well as the ludicrously overblown enka poetics of visiting songsmith Dankichi Nitobe (voiced by drama star Ken Matsudaira, merrily sending himself up). But plaudits are also well-deserved for Okada’s sometime collaborators, director Takayuki Nagai and character designer/lead animator Masayoshi Tanaka. Between them, they craft an image of small-town Japan that beautifully captures its pin-sharp cleanliness, bathed in autumnal light, without ignoring the gunge on the school steps or the cracks on the screen of Aoi’s smartphone. The characters, too, are deceptively simple; viewers might like to look out for some of the swiftly-drawn lines – the sheer spangliness of Dankichi’s costumes, and the grim, taut lips of the grown-up Shinno, less a homecoming hero than a subdued session-musician.

But even Shinno gets to shine in a scene in which actor Ryo Yoshizawa (that’s Kamen Rider Meteor to you) gets to improvise a song with an unplugged electric guitar, at first in his own voice, and then in a pastiche of Dankichi. And when a mishap gives our local heroes a chance to show what they are made of, listen out for Aoi’s punkish rendition of Godiego’s “Gandhara”, transforming it from a gentle elegy into an angry song of protest.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Her Blue Sky is screening at this year’s Scotland Loves Anime.

Leave a Reply