Inu-Oh

August 3, 2023 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

With his film Inu-Oh, Masaki Yuasa turns anime into a concept album which gives the illusion of a live performance in real time, one where we’re slack-jawed witnesses to a new Jimmy Hendrix or Freddie Mercury. Or an old one, as the film takes place in a fantasy historical Japan only a timeline or two away from Samurai Champloo. Modern music reverberates back through the centuries, making dusty scrolls and antique paintings throb to this boombox time machine.

It’s 14th-century Japan, whose self-styled authorities are still melding the island into a nation under their rule. That rule is disturbed by two boys. One is Tomona, a blind musician who plays the lute-like biwa; the other is Inu-Oh (“king of dogs”), who’s cursed by a monstrous body with limbs of all sizes, and a ghastly face under a twisted mask. But they’re really rock gods like Hendrix or Mercury or Jagger, bursting on Japan fully formed.

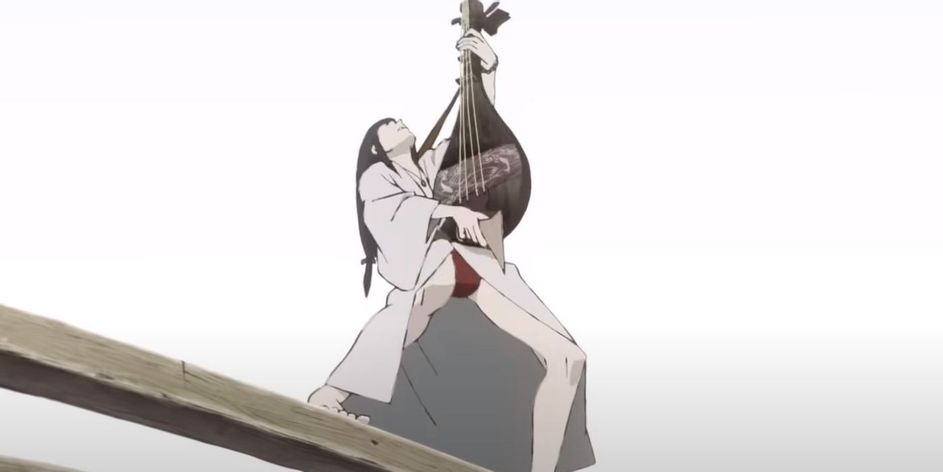

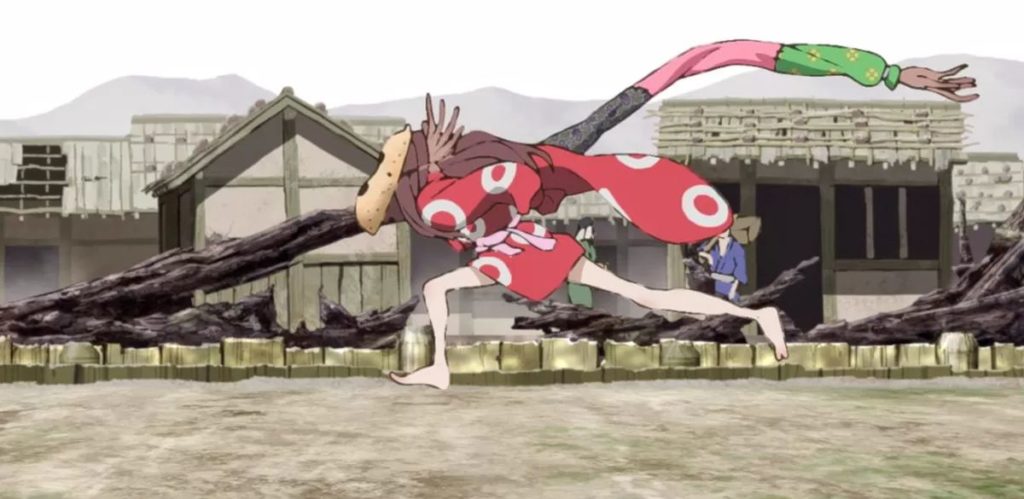

The “real-time” concert scenes take up much of the film; they’re what you go out remembering. It’s often one act after another, alternating Tomona and Inu-Oh (they don’t have what feels like a true duet), with Science Saru’s florid animation and the funk of musician Yoshihide Otomo. Tomona plays his biwa behind his head Hendrix-style, but his Jagger mouth makes him, pouting and grimacing in lip-synched close-up. With the masked Inu-Oh, it’s his splaying limbs, making him a carny contortionist in an age before carnivals. His first song is a gruesome story of dismemberment as he “drops” hands and head for the crowd. You see little boys, the kind who’d often jeer the disabled, gleefully copying Inu-Oh, though he’ll change in ways Bowie would envy.

Both Tomona and Inu-Oh are built up well in the first act, which gives Tomona an elaborate backstory involving relics from an even older history. The key historical reference is the Battle of Dan-no-ura, which Japanese viewers would have studied at school (think Hastings). It happened in 1185, centuries before the film’s main events. This was a sea battle, in the strait between Japan’s mainland and the south island Kyushu, and it culminated in the drowning of a child Emperor, glimpsed in the film, and the start of the shogun regime. Supposedly, a sacred magic sword was lost with the Emperor. It’s sometimes called Kusanagi, the name chosen by the heroine of Ghost in the Shell.

The film’s overture has its own vivid moments, such as the intrepid boy Tomona swimming down into a seabed to probe the secrets in its muck, primal and beautiful. Of course he finds the sacred sword, but the cost for him will be heavy. Meanwhile, Inu-Oh is built up as a self-identified “monster” who’s accepted his cruel label with sly, giggling glee. The first act shows Inu-Oh’s world through his mask’s peepholes; meanwhile, the now blind Tomona perceives the world as a soundscape, with a glorious scene of rain torrenting off a wooden roof.

Later, there’s a revelation about Inu-Oh’s origins which pushes the visuals into horror-psychedelia, as someone explodes like a blood-bag while 2001 is spoofed with a horribly mutating Star Child. In a film forever reminding you of music legends, it makes some sense that Inu-Oh’s story draws heavily on a strip by the manga legend, Osamu Tezuka’s Dororo.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Inu-oh is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply