Mad Max and Anime

October 4, 2015 · 0 comments

By Hugh David.

If there are two live-action English-language movies of the early 1980s that had an enduring effect on Japanese animation beyond all others, they would be Blade Runner (1982) and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981). Of course, Blade Runner was already influenced by the look of Tokyo of the period, but Mad Max 2 was a true original, coming out of Australia like a rocket and blowing the minds of those who saw it the world over (especially if they had not seen Mad Max, which as a small-scale Australian independent film saw less of a wide release than its follow-up). As such, when one sees its influence somewhere, it stands out as tapping George Miller and Byron Kennedy’s screen visions.

If there are two live-action English-language movies of the early 1980s that had an enduring effect on Japanese animation beyond all others, they would be Blade Runner (1982) and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981). Of course, Blade Runner was already influenced by the look of Tokyo of the period, but Mad Max 2 was a true original, coming out of Australia like a rocket and blowing the minds of those who saw it the world over (especially if they had not seen Mad Max, which as a small-scale Australian independent film saw less of a wide release than its follow-up). As such, when one sees its influence somewhere, it stands out as tapping George Miller and Byron Kennedy’s screen visions.

The most obvious one of all is legendary manga and anime franchise Fist of the North Star. Arguably one of the greatest of post-apocalyptic stories, the manga series debuted in the pages of Shonen Jump magazine in 1983, two years after Mad Max 2, and ran until 1988. Creator Buronson (aka Yoshiyuki Okamura, drawing his nom de plume from legendary Hollywood tough guy Charles Bronson) has stated the importance of that film to his now equally established creation. The deserted wasteland, populated by roaming motorised gangs dressed in punk and New Wave-influenced styles, is arguably what stands out most as being drawn from the imagined future of George Miller and Byron Kennedy. Later iterations in animation make it clearer still, and the live-action English language version of it (from Hellraiser II director Tony Maylam) is the ultimate statement in that regard, often feeling more like a studio-bound post-Italian-rip-off homage to the film than an adaptation of the anime.

The most obvious one of all is legendary manga and anime franchise Fist of the North Star. Arguably one of the greatest of post-apocalyptic stories, the manga series debuted in the pages of Shonen Jump magazine in 1983, two years after Mad Max 2, and ran until 1988. Creator Buronson (aka Yoshiyuki Okamura, drawing his nom de plume from legendary Hollywood tough guy Charles Bronson) has stated the importance of that film to his now equally established creation. The deserted wasteland, populated by roaming motorised gangs dressed in punk and New Wave-influenced styles, is arguably what stands out most as being drawn from the imagined future of George Miller and Byron Kennedy. Later iterations in animation make it clearer still, and the live-action English language version of it (from Hellraiser II director Tony Maylam) is the ultimate statement in that regard, often feeling more like a studio-bound post-Italian-rip-off homage to the film than an adaptation of the anime.

Less well known to modern fans, but still considered something of an SF classic by older cognoscenti, the 1985 manga Grey and its subsequent anime Grey: Digital Target (1987) features militarised, motorised action in the kind of desolate badlands of a future earth becoming familiar at this point from Mad Max 2 and by now Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome. That said, creator Yoshihisa Tagami has professed a love of westerns, something Miller and Kennedy have also acknowledged in their vision of Max and his world, and there are other SF influences in the stew, but those handful of action scenes indeed echo Miller & Kennedy’s blocking and editing.

No dispute over Battle Angel Alita, which is another one that bears the clear signs. Running from 1990 to 1995, fans of the 1992 anime may not see those signs, adapting as it does just the first two volumes of the manga. No, it’s the fifth arc, aka Angel of Death, which sees our heroic cyborg Alita (Gally in the original) in a future western scenario that’s pure Mad Max 2: she’s the bodyguard of a train that gets attacked by wasteland bandits in souped-up vehicles, leading to a cross-desert chase to hunt them down. Despite being only halfway through the epic saga, this is arguably the single tightest, best-conceived arc of it, much of which can be attributed, like Mad Max 2, to the story and character “heavy lifting” done by previous arcs, allowing the characters to just get on with their adventure, justifying our combat-trained protagonist’s lonely roles in the bigger plot.

Desert Punk may be more of a late-cycle spaghetti western (comedic stylings and juvenile sexual humour included) updated for the post-apocalyptic setting, and certainly doesn’t have as much vehicular warfare, but the zany characters and their designs nod in the direction of Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome. The same can be said for sci-fi western Trigun, far more a pure western than Mad Max piece, yet also borrowing clearly from Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome in character designs and related elements. 2010’s space race feature Redline makes up for these last two with its frenetic racing carnage on a planet that resembles enough the Earthbound settings of future Australia, certainly capable of filling a hole in Mad Max fans’ hearts in the long wait for Fury Road.

Desert Punk may be more of a late-cycle spaghetti western (comedic stylings and juvenile sexual humour included) updated for the post-apocalyptic setting, and certainly doesn’t have as much vehicular warfare, but the zany characters and their designs nod in the direction of Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome. The same can be said for sci-fi western Trigun, far more a pure western than Mad Max piece, yet also borrowing clearly from Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome in character designs and related elements. 2010’s space race feature Redline makes up for these last two with its frenetic racing carnage on a planet that resembles enough the Earthbound settings of future Australia, certainly capable of filling a hole in Mad Max fans’ hearts in the long wait for Fury Road.

Across the thirty years since the original trilogy ended, anime has clearly kept images and ideas from it alive, absorbing them and spitting them back out fresh. However, in the eleven years it has taken to develop Mad Max: Fury Road, the new vision has clearly returned the favour. While most western critics have locked on to the obvious influences, especially Buster Keaton’s The General, many have failed to unpack the comic book and anime elements. Fury Road originated not with a script, but with a complete storyboard by 2000AD comic book artist Brendan McCarthy, already known for artwork with a punk/post-punk feel to it. His kineticism has not only survived other production artists and the physical realities of making the film, but director Miller, working without a co-director for the first time in the series, has done things the way anime often does. Charlize Theron’s one-armed warrior seems to have walked out of an anime, while the moment when she uses Max’s shoulder as support for a long-range rifle shot is practically a direct lift from the Battle Angel Alita story mentioned above. The plot point of the rock archway and its use to block vehicles was already used in episode 3 of Desert Punk. The point-of-view shots, particularly for Max in the middle of the first major chase, will feel familiar to fans of anime in the same way that the work from the Wachowskis and Neil Blomkamp often does, given their propensity to stage, shoot and edit live-action the way anime builds sequences on screen.

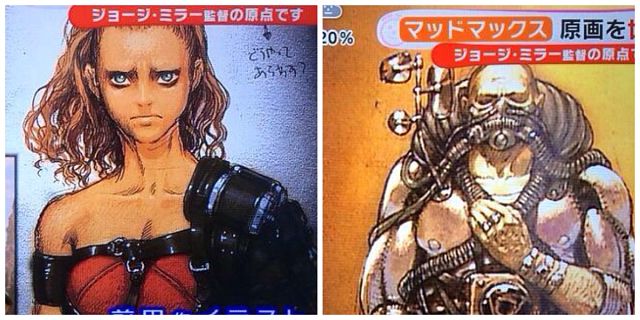

However, most intriguing of all is that, given Warner’s success worldwide with The Animatrix and Universal’s subsequent pursuit of tie-in videos for genre properties (including Riddick: Dark Fury and Van Helsing: the London Assignment), plans for a Fury Road tie-in anime a la Batman – Gotham Knight fell through despite being mentioned in the run-up to the film’s release. Thankfully the Internet has come to the rescue of international fans, allowing us to see the Japanese TV report that reveals the script was co-written by Miller with Nico Lathouris and designs were by anime legend Mahiro Maeda, focusing on Furiosa’s back-story. It’s safe to say that this is probably the same script used as the basis of DC Comics/Vertigo’s newly-released Mad Max: Fury Road – Furiosa #1, as Miller & Lathouris are officially co-credited as writers on it (even though it’s been made quite clear that writer Mark Sexton did the comic adaptation of that) but Tristan Jones’ art does not seem to be working from Maeda’s work. Sadly, we’ll have to chalk this up as another great lost opportunity in the world of international co-production.

However, most intriguing of all is that, given Warner’s success worldwide with The Animatrix and Universal’s subsequent pursuit of tie-in videos for genre properties (including Riddick: Dark Fury and Van Helsing: the London Assignment), plans for a Fury Road tie-in anime a la Batman – Gotham Knight fell through despite being mentioned in the run-up to the film’s release. Thankfully the Internet has come to the rescue of international fans, allowing us to see the Japanese TV report that reveals the script was co-written by Miller with Nico Lathouris and designs were by anime legend Mahiro Maeda, focusing on Furiosa’s back-story. It’s safe to say that this is probably the same script used as the basis of DC Comics/Vertigo’s newly-released Mad Max: Fury Road – Furiosa #1, as Miller & Lathouris are officially co-credited as writers on it (even though it’s been made quite clear that writer Mark Sexton did the comic adaptation of that) but Tristan Jones’ art does not seem to be working from Maeda’s work. Sadly, we’ll have to chalk this up as another great lost opportunity in the world of international co-production.

Mad Max: Fury Road, is out today on UK Blu-ray.

anime, Australia, Battle Angel Alita, fist of the north star, influences, Japan, Mad Max, manga, movies, The Road Warrior

Leave a Reply