Gundam: The Exhibition

September 1, 2015 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond. Pictures by Carlos Nakajima.

The towering Roppongi Hills complex in Tokyo is the kind of structure that you could imagine being blasted into orbit to become a space habitat for some wide-eyed anime space opera. Not yet, alas, but until September 27 it’s playing host to “The Art of Gundam,” an extensive tribute to the original TV series, and an excellent overture to the upcoming Blu-ray.

It’s notable that this huge exhibition is very specifically about the first Gundam. At the end, it acknowledges the many Gundams that have come since, with some character art from the current Gundam – The Origin and a funky projected montage of the whole franchise. But the exhibition suggests that the first 1977 series sank far deeper into the Japanese psyche, into the pop-culture mainstream, than any of its successors. In that way, you could compare the first Gundam to the 1960s Star Trek with Kirk, Spock and McCoy. Perhaps that’s because of Gundam’s epic space-opera vision (far less cheery than Star Trek, yet still with room for thrills and heroes); or its provocative notion of the next human evolution, the Newtypes; or perhaps it’s all down to the endless duelling between Char Aznable and Amuro Ray.

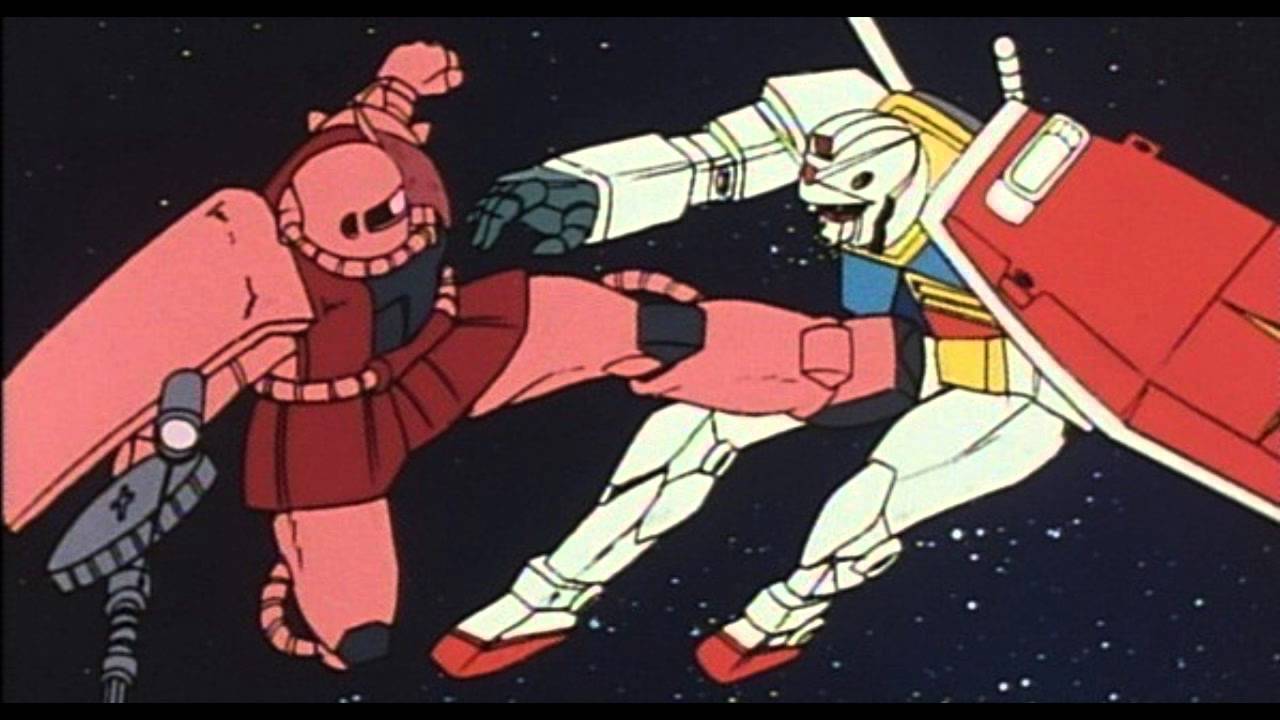

Located at the top of Roppongi Hills’ tower, the exhibition has some very useful text in English, but much of it is Japanese-only, including audio guides delivered by Gundam voice-actors. Still, it’s easy to follow what’s going on, particularly if you have some familiarity with the Gundam story. It starts in theme-park mode, with visitors entering the exhibit through a theatre mock-up of the White Base spaceship. Here you can watch – what else? – a desperate mecha battle between Char and Amuro as we hurtle into Earth’s atmosphere (it’s a high-tech recreation of part five of the series).

Located at the top of Roppongi Hills’ tower, the exhibition has some very useful text in English, but much of it is Japanese-only, including audio guides delivered by Gundam voice-actors. Still, it’s easy to follow what’s going on, particularly if you have some familiarity with the Gundam story. It starts in theme-park mode, with visitors entering the exhibit through a theatre mock-up of the White Base spaceship. Here you can watch – what else? – a desperate mecha battle between Char and Amuro as we hurtle into Earth’s atmosphere (it’s a high-tech recreation of part five of the series).

The exhibit proper starts with the early development of the series. One of the first ideas was to adapt an existing adventure novel, Jules Verne’s Deux Ans de Vacances, a.ka. Adrift in the Pacific, about a bunch of children marooned without adult help. Another iteration was envisaged as a fight between 26 men on a battleship and a hundred thousand-strong army of “Gunboy” soldiers (it’s what the Spartans of 300 would call good odds). The exhibit text mentions that in this version, the enemies wouldn’t have been from Earth, though it’s unclear if they would have still originated on Earth (as in Gundam) or if they would have been aliens.

It’s also mentioned that in the early development there were no robots in the story until the sponsors insisted on them. The sponsors wanted ‘good-looking’ robots for the Earth Federation characters, but gave the artists a freer hand in inventing the Zeon mecha. And at first they weren’t big robots; the idea was to make them only 2.5 metres tall, closer to the robot suits in Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers than anime ‘super robots’ like Mazinger Z. It was only later that they grew to the building-sized Gundams that are so iconic today.

One idea that seems constant through development, though, is the “story of a group of boys thrown into extreme conditions of war” (the actual Gundam added some women, too). The exhibition includes planning documents from a time was Gundam was still called Gunboy. The main characters are already there: 15 year-old hero Amuro, the captain Bright Noa, female crewmember Mirai and their scarlet enemy Char. The early drawings, though, have some interesting divergences. One picture shows Bright with yellow, perhaps ‘blond’ hair, and there’s a drawing of another woman, Hachijo Shima, who didn’t make the final show. (Interestingly, a character of the same name apparently appeared in For the Barrel, an obscure Gundam story published in Newtype magazine.) We also see early drawings of the White Base warship before it found its final shape, and mecha designs that didn’t make the cut.

The exhibition moves through a torrent of Gundam visuals from all stages of production. There’s a mock-up of Tomino’s desk, storyboards on display; there are original drawings and layouts; there are paintings created for box covers and cinema posters (the 1977 series was compiled into three movies). There are some model dioramas behind glass, ingeniously magnified. There are also original animation cels on display, though the exhibit notes that these need to be switched once a fortnight, to stop their colours fading.

The exhibition moves through a torrent of Gundam visuals from all stages of production. There’s a mock-up of Tomino’s desk, storyboards on display; there are original drawings and layouts; there are paintings created for box covers and cinema posters (the 1977 series was compiled into three movies). There are some model dioramas behind glass, ingeniously magnified. There are also original animation cels on display, though the exhibit notes that these need to be switched once a fortnight, to stop their colours fading.

Three Gundam artists who worked with Tomino are highlighted by the exhibition. The best known is Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, Gundam’s animator and character designer; he’s also the author of the epic Gundam – The Origin manga and chief director of its anime adaptation. The other artists are Mitsuki Nakamura, Gundam’s Art Director, and Kunio Okawara, the Mecha Designer. In a time when we’re used to artists fighting over who “really” created a beloved property – like the row over Space Battleship Yamato – it’s refreshing to find an exhibit that celebrates the collaboration of talents. The text notes, for instance, how Yasuhiko used Okawara’s already brilliant designs to give vitality to anime battles.

At least in the exhibition, it’s the showcases of Nakamura’s and Yasuhiko’s art that are most revelatory. Nakamura dominates a section called “In the View of the Future,” with the text explaining how Gundam’s universe of space colonies was shaped by the 1970s awareness of an exploding population and environmental crises. Gundam was also directly inspired by an American physicist, Gerard K. O’Neill, who wrote a 1976 book proposing the kind of cylindrical space colonies depicted in the show.

There are a huge number of pencil design sketches, while the beautiful paintings of space colonies and craft, some blown up to large-scale, reignite the sense of wonder that we used to get in children’s space books of yesteryear. However, these hopeful dreams of interstellar technology are counterbalanced by the terrors of Armageddon. One of the blown-up paintings, taken from Gundam’s opening sequence, shows a gargantuan space colony crashing down to Earth to annihilate a city. It makes Avengers: Age of Ultron look like small beer.

But even that is surpassed by the section on Yasuhiko’s character drawings. These are immensely dynamic and expressive, with faces that are desperate, furious, leering or stricken. Roughly shaded in felt-tip, they look timeless today in a way that the 1970s TV animation does not, highlighted by videos of key Gundam scenes that let you compare the art side by side. Even more than the opening CG battle, these rooms truly give the feeling that you’re standing inside Gundam’s act of creation.

The Art of Gundam exhibition plays until September 27 at the Mori Arts Center Gallery in Roppongi Hills. It is open seven days a week from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., with the last admission at 7 p.m. The closest station is Roppongi station on the Hibiya and Oedo subway lines; take exit 1C from Hibiya or exit 3 from Oedo. Tickets are 2,000 yen for adults, 1,500 yen for high school students, and 800 yen for elementary schoolers.

Leave a Reply