Anime: A Critical Introduction

October 25, 2015 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Rayna Denison chooses her title with robust caution: her new book, Anime: A Critical Introduction, is an introduction for and occasionally about critics, examining the arguments and materials with which readers can approach Japanese animation. Her new book is part of Bloomsbury’s “Film Genres” series, although she swiftly establishes cast-iron criteria for discussing anime within this context – anime is a medium that contains many genres and brands, and Denison offers insight into a selection of these, with plenty of jumping-off points for other researchers.

Rayna Denison chooses her title with robust caution: her new book, Anime: A Critical Introduction, is an introduction for and occasionally about critics, examining the arguments and materials with which readers can approach Japanese animation. Her new book is part of Bloomsbury’s “Film Genres” series, although she swiftly establishes cast-iron criteria for discussing anime within this context – anime is a medium that contains many genres and brands, and Denison offers insight into a selection of these, with plenty of jumping-off points for other researchers.

Recent anime critics like Hu, Condry and Steinberg are richly cited, and grounded within a seven-point statement of intent. This is more important than it seems – as I have noted elsewhere, far too many accounts of anime devolve into what some fans I met think about some films they have seen, but this book is a shining example of how to do it right.

Recent anime critics like Hu, Condry and Steinberg are richly cited, and grounded within a seven-point statement of intent. This is more important than it seems – as I have noted elsewhere, far too many accounts of anime devolve into what some fans I met think about some films they have seen, but this book is a shining example of how to do it right.

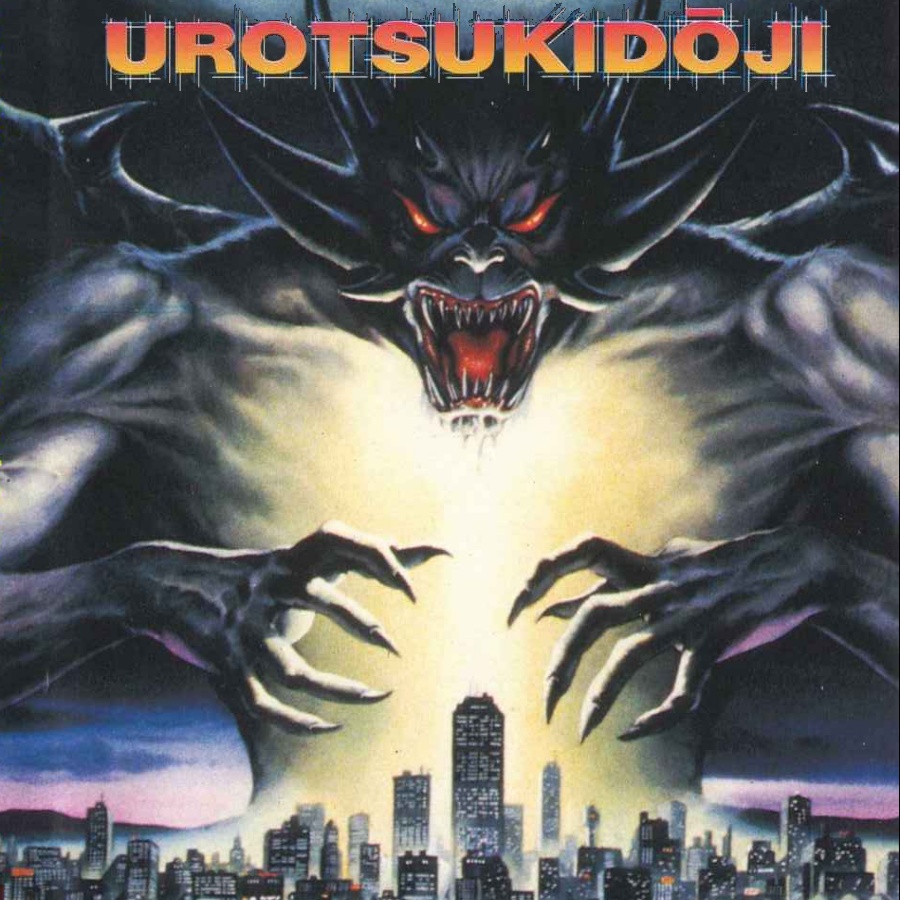

A section on the notorious video-nasty Urotsukidoji playfully bills itself as a “legend of a controversy,” delving into the archives to read the 1990s newspaper articles that have long been derided by anime apologists. Denison warns against the temptation to quote others’ quotations, suggesting that even the most fulminating anti-anime screeds offered balance and dissent in their less quoted passages, now forgotten by critical memory.

It is heartening, as well, to see her poking around in the stacks, giving Antonia Levi’s ground-breaking (but infuriating) Samurai From Outer Space its due, as well as quotes from the likes of Fred Patten, Frederik L. Schodt, and McCarthy & Clements (remember them?). Her bibliography is admirably loaded with overlooked ephemera and YouTube videos alongside the usual suspects. One section even examines the vocabulary of a couple of early Anime UK magazines – leaving this reader wanting more. Using Denison’s methods, someone should investigate the entire span from 1991-2000, as seen through the overlapping runs of Anime UK/FX and Manga Mania/Max and the changing sense among the writers  and editors of their vocation. I particularly enjoy her concentration on the terms that writers used, and what they thought they meant at the time, because I spent much of the 1990s trying to stop them putting their feet in it. She chides me for being “devastatingly dismissive” of certain shibboleths, but that’s because it was once my job to stop anime journalists from throwing around Japanese jargon that neither they nor their readers understood. It drove me to write the Manga Max style guide in 1998, which tried to prevent some of the solecisms she identifies. “If you don’t listen to me,” I should have warned them, “in 20 years’ time Rayna Denison will subject you to a sharp-eyed and close reading, and then you’ll be sorry!”

and editors of their vocation. I particularly enjoy her concentration on the terms that writers used, and what they thought they meant at the time, because I spent much of the 1990s trying to stop them putting their feet in it. She chides me for being “devastatingly dismissive” of certain shibboleths, but that’s because it was once my job to stop anime journalists from throwing around Japanese jargon that neither they nor their readers understood. It drove me to write the Manga Max style guide in 1998, which tried to prevent some of the solecisms she identifies. “If you don’t listen to me,” I should have warned them, “in 20 years’ time Rayna Denison will subject you to a sharp-eyed and close reading, and then you’ll be sorry!”

The latter part of the book shows Denison at her best, offering exemplary chapters on the way that anime is sold at trade fairs (an interesting exercise at the under-examined level of distribution), and the discourse of a single genre, anime horror, as debated by certain critics. My favourite chapter, on Ghibli, is the opening argument for what, one hopes, will someday become an entire book on the studio. It concentrates not on the blockbusting feature output, but on the company’s many shadowy activities: sub-branches, commercial work and below-the-line contracts, and revealing there is far more to it than all those world-beating, award-winning features that get all the attention. Making welcome use of Japanese-language materials, Denison tackles the producer Toshio Suzuki, once simply overlooked as “the other guy” in publicity photographs, but increasingly recognised (partly through his own media manipulations) as a driving force with equal weight to that of the hallowed Miyazaki and Takahata. Revisiting arguments from her own doctorate, Denison investigates the way that Ghibli has been sold, mounting the opening stages of what is sure to be a revealing investigation into the company’s internal conflicts and external presentations.

Reflecting her background and specialty, Denison often prefers the post-modern tail-chasing of discourse, in which reality can degrade to a fuzzy, indistinct quantum, the fact of an occurrence fading while people argue about it. While such deconstruction can be fun, illuminating and productive, it also risks privileging any form of disagreement, no matter how ill-founded, in pursuit of some kind of “balance.” This is catnip for cultural theorists, but a frustration for historians like me, who are expected to decree some sources more equal than others.

Reflecting her background and specialty, Denison often prefers the post-modern tail-chasing of discourse, in which reality can degrade to a fuzzy, indistinct quantum, the fact of an occurrence fading while people argue about it. While such deconstruction can be fun, illuminating and productive, it also risks privileging any form of disagreement, no matter how ill-founded, in pursuit of some kind of “balance.” This is catnip for cultural theorists, but a frustration for historians like me, who are expected to decree some sources more equal than others.

Occasionally, and only occasionally, Denison is too busy polishing her shiny arguments to see what is actually being said. She discusses, for example, two accounts of Osamu Tezuka’s involvement in Alakazam the Great, seemingly without noticing that neither story contradicts the other. Simply because Tezuka denied he was the director, it doesn’t mean that he didn’t spend weeks drawing storyboards in his office. There is a world of difference, in aims and execution, between my Mechademia paper on Tezuka and Fred Patten’s earlier magazine anecdote about the time Tezuka dismissed a poorly-worded question on a convention panel, but the latter is presented as some sort of anachronistic rebuttal to the former. In fact, I see no reason why Patten and I would not entirely approve of each other’s statements. But if the facts are in agreement, and we are in agreement, then it is only the critic on the sidelines who needs to shape up. There are plenty of debates to be had about Tezuka’s anime career, but frankly this is not one of them.

Similarly, while it’s true in the aforementioned Urotsukidoji discussion that newspaper articles often contained half-hearted attempts to represent minority views, a closing soundbite from a passing fanboy hardly counters a headline screaming CARTOON CULT WITH AN INCREASING APPETITE FOR SEX AND VIOLENCE. In a phenomenological sense, turning such scholarly hand-wringing on the scholars themselves, I question whether anyone in 1993 was giving newspaper articles the consideration that Denison herself wields with 20/20 hindsight. Far more people read (and remembered) the headlines than the final paragraphs; these sources, too, have their contexts and misprisions, their performances and subversions. Denison makes this point, too, although she does not always apply it.

Similarly, while it’s true in the aforementioned Urotsukidoji discussion that newspaper articles often contained half-hearted attempts to represent minority views, a closing soundbite from a passing fanboy hardly counters a headline screaming CARTOON CULT WITH AN INCREASING APPETITE FOR SEX AND VIOLENCE. In a phenomenological sense, turning such scholarly hand-wringing on the scholars themselves, I question whether anyone in 1993 was giving newspaper articles the consideration that Denison herself wields with 20/20 hindsight. Far more people read (and remembered) the headlines than the final paragraphs; these sources, too, have their contexts and misprisions, their performances and subversions. Denison makes this point, too, although she does not always apply it.

There are also a few sources I wish she had at least cited so that her readers would know they are even there – Tony Rayns’ early coverage of Akira in Monthly Film Bulletin, for example, or Kim Newman’s incisive review of Ghost in the Shell in Sight & Sound, both of which I regard as immensely influential on the shaping of contemporary opinions, particularly among the film studies community that Denison now represents. The 1.1 million-word Anime Encyclopedia, several entries from which could have provided handy material for her, is also notable by its omission. I’ve grown used to academia’s aversion to this project on methodological grounds, but even if you’re going to write it off as a “fan” source, then surely it’s a pretty big fan source?

But Denison’s book will undoubtedly form a welcome core text of anime appreciation among film scholars. She repeatedly points her readers at the radical differences that can arise between “anime” at home and abroad, but also at different times and among different audiences. Hopefully it will prevent a new generation of writers about anime from making at least some of the mistakes of their predecessors, and create new materials for the readers of the future… hello anime researchers of the year 2035… if you are reading this, then there is still hope.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

anime, books, criticism, film, history, Japan, Jonathan Clements, Rayna Denison, reviews, Studio Ghibli, Urotsukidoji

Leave a Reply