Aya Suzuki: In Her Own Words

July 30, 2016 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The guests at this year’s London Anime and Gaming Con included animator Aya Suzuki, who has worked on a remarkable list of productions. Following a four year stint on Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist, she worked on Satoshi Kon’s unfinished last film The Dream Machine, Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, Fuminori Kizaki’s Bayonetta: Bloody Fate and Masaaki Yuasa’s Ping Pong. She’s also consulted studios such as WIT and Trigger on how to upgrade their paper-based practices for the digital age.

The guests at this year’s London Anime and Gaming Con included animator Aya Suzuki, who has worked on a remarkable list of productions. Following a four year stint on Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist, she worked on Satoshi Kon’s unfinished last film The Dream Machine, Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, Fuminori Kizaki’s Bayonetta: Bloody Fate and Masaaki Yuasa’s Ping Pong. She’s also consulted studios such as WIT and Trigger on how to upgrade their paper-based practices for the digital age.

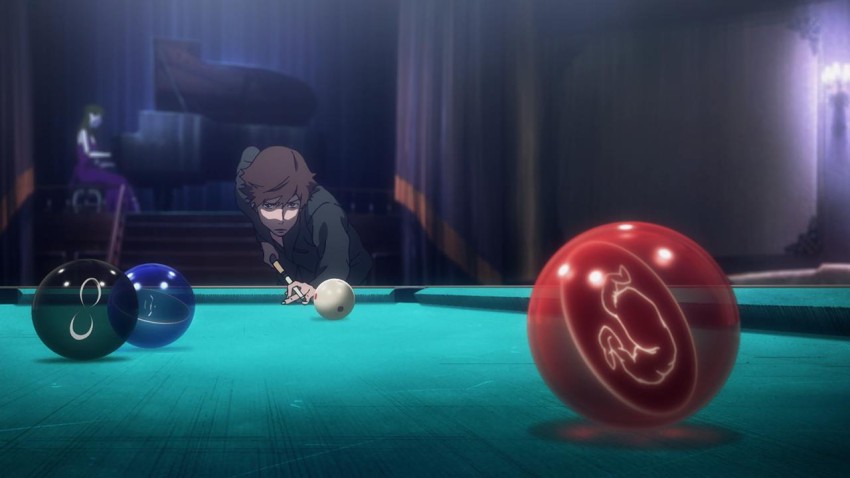

Here she talks about them all, plus her stint on the Madhouse film Death Billiards, the basis for the series Death Parade.

On working on Wolf Children.

“When I had my first meeting with Hosoda about the scenes of the baby wolf children, I asked him what I should use for reference, because the storyboards weren’t that detailed. He gave me a DVD, and it was all videos of his dog (laughs). I asked, ‘Do you want the children to be humans or dogs?’ He said, he just gave me the video because he thought it was cute! I also watched Japanese documentaries with lots of footage of children growing up, their daily lives, but those videos mostly only show the nice side of children. It was a struggle to find children doing really horrible things!

“Hosoda didn’t have children at that time, he had his son after the movie was made. I asked him: Wouldn’t it be better to make the film after he had children? He said, no, because it would be a totally different film. The reason why he made that project is that it was based out of his fantasy of having children, and once that fantasy was broken, the film wouldn’t be the same. I think the hardship of parenthood in Wolf Children isn’t realistically portrayed; everything is kind of all right. Hosoda was saying that if he made the film after having children, then it would be a darker story. Being a single mum isn’t easy, but he made it a bit lighter; I think that’s because it was based on a pure fantasy of parenthood.”

On working on Ping Pong.

“The production assistant for [Ping Pong director] Masaaki Yuasa had previously been the production assistant at Studio Chizu, and I knew her from Wolf Children. She was collecting animators for Ping Pong and contacted me. At that point, my schedule was jam-packed, but I said yes because I wanted to work on a Yuasa project. [Suzuki contributed around ten shots to episode 2.]

“The production assistant for [Ping Pong director] Masaaki Yuasa had previously been the production assistant at Studio Chizu, and I knew her from Wolf Children. She was collecting animators for Ping Pong and contacted me. At that point, my schedule was jam-packed, but I said yes because I wanted to work on a Yuasa project. [Suzuki contributed around ten shots to episode 2.]

“I worked from home in London, doing everything by email and skype. There was no rejection of digital animation, unlike most anime studios. [In contrast to American and European studios, anime studios still largely work on paper.] Although the production was at Tatsunoko, Yuasa was setting up his studio, Science Saru, and I believe they did the in-betweens clean-up there. But I think Yuasa still checks by paper, so they were printing out my animation and checking it by pencil, scanning it back in and sending it back to me to finish my work.

“Everything worked smoothly; the only thing was that I struggled to find the time. I remember doing it over Christmas and New Year. It wasn’t particularly the difficulty of the shots, but the drawing style. I was told to be true and honest to the original manga by Taiyo Matsumoto. I read the sequence I was working on and finally just blew it up and traced it; I couldn’t draw that style freehand. But this doesn’t always work in animation, because the frame may not be the right size, so I still had to draw it again; but I traced the images initially to capture the feeling of the drawings.”

On how Yuasa’s style can be made within the anime industry.

“I don’t think what Ping Pong did is so crazy. Yuasa’s style is unique, but he’s done that over and over again with anime like Kaiba and Kemonozume. The style is actually possible to manufacture; the animation director controls the drawings, and an assistant director controls the clean-ups. If you can train the main staff well – and Yuasa usually has the same team – then it’s fine. Yuasa always manages to come up with something visually quirky, yet smartly maintain it within the existing anime production pipeline. Remember, he started his directorial career working on commercial projects like Crayon Shin-chan and Chibi Maruko-chan. People say he’s a unique artist, but he also worked on commercially successful family TV series.”

“I don’t think what Ping Pong did is so crazy. Yuasa’s style is unique, but he’s done that over and over again with anime like Kaiba and Kemonozume. The style is actually possible to manufacture; the animation director controls the drawings, and an assistant director controls the clean-ups. If you can train the main staff well – and Yuasa usually has the same team – then it’s fine. Yuasa always manages to come up with something visually quirky, yet smartly maintain it within the existing anime production pipeline. Remember, he started his directorial career working on commercial projects like Crayon Shin-chan and Chibi Maruko-chan. People say he’s a unique artist, but he also worked on commercially successful family TV series.”

Suzuki cites Isao Takahata’s My Neighbours the Yamadas and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya as far more ‘out of the box’ than Ping Pong in terms of their production. Both films had three separately drawn layers in every frame, meaning they required triple the number of drawings as an average animated film.

On comparing Ping Pong and Evangelion fans.

“I cannot talk for all anime fans out there, but I would say the majority audience is probably slightly different. The critics love Yuasa. Somebody who takes film seriously, or who appreciates art would love Ping Pong; but it probably won’t appeal to someone who wants to collect Gundam toys. Yuasa doesn’t always have a female character that is marketable on the shelf next to Nami from One Piece or Asuka from Evangelion. That is a big issue with anime; toy companies are always saying, where’s that pretty girl we can sell as a figurine? Evangelion is full of that: the machines, the characters, and adding more characters.”

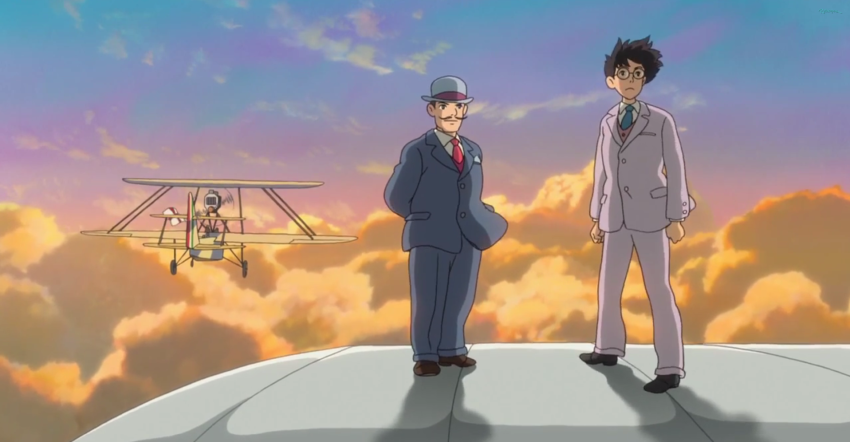

On working at Ghibli.

“The Wind Rises was one of the most difficult projects I worked on. Even though it’s of considered a great honour to work on a Miyazaki film, it’s actually quite a struggle for Miyazaki to find animators because not everybody wants to do it. Very little of your work stays as it is – my work on Death Billiards and Wolf Children was more or less untouched, whereas Miyazaki’s way of working is that he’ll correct each and every frame, drawing all over it. So as an animator you feel a little demoralised…

“The Wind Rises was one of the most difficult projects I worked on. Even though it’s of considered a great honour to work on a Miyazaki film, it’s actually quite a struggle for Miyazaki to find animators because not everybody wants to do it. Very little of your work stays as it is – my work on Death Billiards and Wolf Children was more or less untouched, whereas Miyazaki’s way of working is that he’ll correct each and every frame, drawing all over it. So as an animator you feel a little demoralised…

“Between Japanese animators I know, Ghibli doesn’t have the best reputation, not because it’s a bad studio but it can be quite disheartening for an artist. But having said that, it was a great experience to work on The Wind Rises. Working with Miyazaki was one of my dreams, one of the reasons I became an animator.”

On animation aesthetics.

“I think fans definitely like the big action scenes… but if you go deep among the professionals, they actually rate the people who can do the subtle, minimalistic animation more, I think. I’m comfortable doing subtle animation, because I relate to it more. Death Billiards was my first big fight, and it definitely didn’t come easily. Shinich Kurita, the animation director, helped a lot; he’s a martial arts, kung fu movie geek, and animation director on many of the Bleach projects.

My favourite Japanese animator is probably Takeshi Honda, who gets both ends perfectly – he can do big action scenes and very subtle scenes. His acting is very emotional. I think anime often tends to be a little bit cold, a bit plastic, whereas his acting is so real… I particularly like his animation and animation direction on the old Evangelion episode 2 and on Millennium Actress.”

On male and female animators.

“I do think there is a difference between them. I’m not saying it’s concrete – there are a lot of young female animators, for instance from Gainax, who do action scenes – but in general, women do relate more to subtler animation because we’re slightly more emotional creatures, that’s where our focus is. However, Masashi Ando [a male animator] tends to lean towards more emotional, subtle acting… At the same time, there’s Atsuko Tanaka [a female animator] who did the earthquake in The Wind Rises.”

On the differences between anime studios.

“They all feel different. The interesting thing is that I did quite a few projects at Madhouse, and it feels different depending on the team. The Death Billiards team, for example, was very tame; we were girls in our twenties. For our wrap party, we went strawberry picking (laughs).

“They all feel different. The interesting thing is that I did quite a few projects at Madhouse, and it feels different depending on the team. The Death Billiards team, for example, was very tame; we were girls in our twenties. For our wrap party, we went strawberry picking (laughs).

I remember meeting the Studio Trigger guys in America and they were buying marshmallow guns, and they said they were going to shoot them in the studio. My wildest team was when I was working on Satoshi Kon’s Dream Machine, when he would take us out for a drink. Insane amounts of alcohol were consumed and it wouldn’t be a matter of missing the last train but rather which first train would we take?”

On animators’ working hours.

“Most animators tend to work long hours but that’s not because it’s forced on us; we do it quite voluntarily. Not all quotas set by studios are unreasonable. If the studio says it wants thirty seconds in week, and you want to work normal hours, you drop the quality. However, most animators don’t want to do that, they want to make it good. When animators get stuck in, it becomes our own little baby… At the end of the day, we are all artists.

“You see all those documentaries of Japanese animators working until midnight without sleep – they don’t have to! All they’d have to do is adjust the quality according to the schedule – the producer or director might be pissed off, but it’s not the animator’s fault. Also, a lot of the time the animators are rocking into work late, so they’re actually working quite normal hours, not that different from a normal office person. There are animators who’d work two days straight without sleeping, then take a day off; then two days straight and take a day off… But that’s three days off a week, more than an average person!”

On what anime directors have in common.

“All the directors I’ve worked with, the similarity is they study like mad; they read and research and they’ve been like that since childhood, as far as I know. Miyazaki knows absolutely everything to do with planes. Hosoda reads like crazy. Fuminori Kizaki’s knowledge of anything is just phenomenal. Satoshi Kon wanted to be a comic-book artist and knew comics language.

“Directing was not Kon’s initial goal; he ended up directing because he was asked. So he locked himself in his apartment for a week, watching movies non-stop and reading film books, analysing filmic language. He said people don’t become film directors that way; they love film from since they were little, so Kon thought the only way he could direct was by catching up on that knowledge. Until he died, he was studying.

“These directors are big film geeks and book nerds, very intelligent people. You throw them any kind of subject and they’ll throw it back ten times harder.”

On anime’s paper-based work processes.

“Japan is very much paper-based – they scan it and paint it digitally. I’m now trying to move the industry towards the digital. [Suzuki says she animates much faster digitally than she does on paper, and that if anime moved more to digital, it might improve animators’ salaries without having to increase budgets.] I don’t think the software is decided yet. Ping Pong used Flash, which I think is okay, but it’s definitely not a long-term solution because Flash is not being developed any more. It’s going to have to switch at some point.

“I think the anime industry is waiting for a Japan-developed software, because most software which is currently out there and usable is American or French. The Japanese want something that’s language-friendly, and catered towards the anime industry.”

Aya Suzuki is now working on the CG feature Gnomeo & Juliet: Sherlock Gnomes, directed by John Stevenson, who co-directed the original Kung Fu Panda. For more on Suzuki’s career, see her blog and this interview.

Our grateful thanks to the staff of the London Anime and Gaming Con for making this interview possible.

animation, anime, Aya Suzuki, Death Billiards, Dream Machine, Japan, Mamoru Hosoda, Masaaki Yuasa, Ping Pong, Satoshi Kon, Studio Ghibli, The Illusionist, Wolf Children

Leave a Reply