Black Mirror to Anime

January 2, 2019 · 2 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

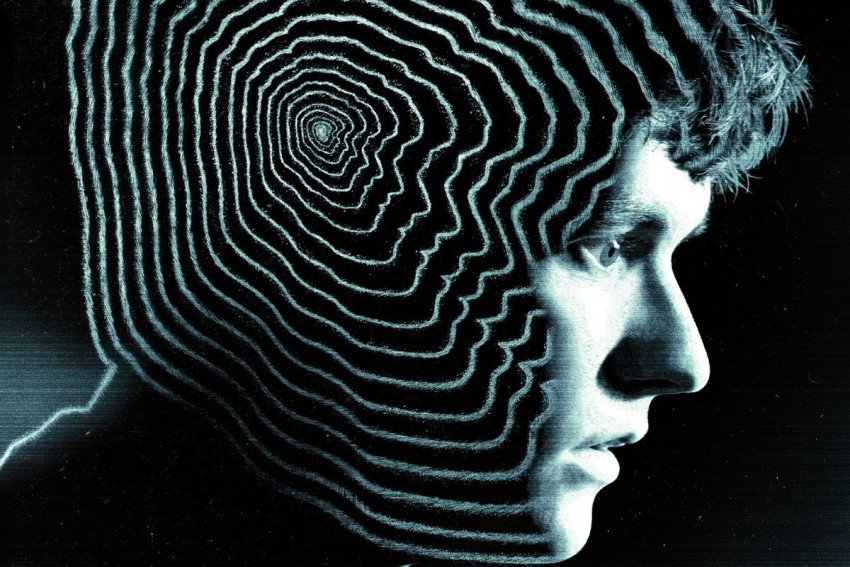

One of the surprise media talking-points over this Christmas was the new episode of the acclaimed anthology series Black Mirror. Called “Bandersnatch,” it was released on Netflix on 28th December, written by series creator Charlie Brooker. It’s a story about multi-choice, branching narratives. The twist is that it’s a multi-choice, branching story itself. At frequent points in the action, two choices pop up at the bottom of the screen, and you have a few seconds to pick one with your remote or mouse… and the drama continues smoothly down whichever branch you pick. Sugar Puffs or Frosties? It’s your call. Bury a body, or chop it up? Likewise.

One of the surprise media talking-points over this Christmas was the new episode of the acclaimed anthology series Black Mirror. Called “Bandersnatch,” it was released on Netflix on 28th December, written by series creator Charlie Brooker. It’s a story about multi-choice, branching narratives. The twist is that it’s a multi-choice, branching story itself. At frequent points in the action, two choices pop up at the bottom of the screen, and you have a few seconds to pick one with your remote or mouse… and the drama continues smoothly down whichever branch you pick. Sugar Puffs or Frosties? It’s your call. Bury a body, or chop it up? Likewise.

You may wonder why we’re talking about “Bandersnatch” on AllTheAnime. The reason is it has some fascinating potential for Japanese media. Ironically, “Bandersnatch” has only one Japanese reference in it, and it’s a bit of a howler. In one of the branching scenes, we visit the home of a successful games programmer called Colin, who’s a major character in the story. Prominent in his room is a giant reproduction of an apocalyptic image from the Akira manga by Katsuhiro Otomo – this one here, from the middle of the strip. It looks dead cool. The problem is “Bandersnatch” is emphatically set in 1984, when Otomo almost certainly hadn’t reached that part of the manga, and only a miniscule number of British people had even heard of manga. (The manga’s English translation started in 1988; the film reached Britain in 1991.)

Otherwise, “Bandersnatch”s obvious hat-tips are to the “multi-choice” media that were popular with British kids and teens in 1984. The story involves a 19-year-old programmer, Stefan, who’s trying to create an innovative adventure game. There’s a dialogue reference to the fondly-remembered 1982 Hobbit game which embedded certain phrases into a generation’s subconscious, like “Thorin sits down and starts singing about gold.” But in “Bandersnatch,” Stefan’s game is adapted from a (fictional) interactive book, clearly modeled on such kid-lit as 1979’s The Cave of Time from America and 1982’s The Warlock of Firetop Mountain from Britain. Both spawned massive franchises that ran well into the 1990s.

But today, the “multi-choice” story is most popular and influential in Japan. Many readers will know why; the “Visual Novel” game industry, where games choose their way through a continually-branching story, typically told through on-screen prose, anime-style pictures and sometimes anime-style voice-acting. For readers unfamiliar with Visual Novels, they’re often cutesy affairs like this – sometimes interspersed with X-rated shenanigans. But they can also be dramatic affairs like this, the original version of Steins;Gate.

Of course, there are analogous games still being made in the West – for example, the acclaimed Walking Dead interactive games by Telltale Games. Countless other Western games offer players huge amounts of choice in what to do – Red Dead Redemption 2 is an extreme case. Indeed, it’s he huge amount of choice given players, including the ability to do all kind of bad things, that helped throw the Grand Theft Auto games into controversy.

Of course, there are analogous games still being made in the West – for example, the acclaimed Walking Dead interactive games by Telltale Games. Countless other Western games offer players huge amounts of choice in what to do – Red Dead Redemption 2 is an extreme case. Indeed, it’s he huge amount of choice given players, including the ability to do all kind of bad things, that helped throw the Grand Theft Auto games into controversy.

But an experience of that kind would be plainly impossible to recreate with either live-actors or “pre-determined” animation. The most you can do is punctuate a game with special cutscenes, often done in mocap but occasionally created in anime, as with Ghibli’s contributions to Japan’s Ni no Kuni. Its trailer illustrates the hybrid nature of such games very well.

Visual novels have always been linked with anime. In his book Anime: A History, Jonathan Clements says that Visual Novels “might be regarded as the apotheosis of limited animation, in which only a few hundred still images appear in the course of a story that lasts for several hours.” In the twenty-first century, Visual Novels have been successfully adapted as anime, with landmarks including the romantic drama Clannad, the science-fiction Steins;Gate and the fantasy epic Fate/stay night. And even the anime versions often highlight the branching nature of their source material.

The gigantic Fate/stay night game, for example, has been adapted umpteen times by two different studios. The original game has a fundamental three-way “split” early on, with each alternative story bringing a different heroine to the fore beside the hero Shiro, and highlighting different themes. The different anime versions tend to follow one of these alternate storylines, perhaps patching elements from the others; the alternate pathways are tagged Fate, Unlimited Blade Works and Heaven’s Feel. Any anime fan who’s followed the franchise is familiar with diverging plotlines, even if they’ve never played the source game.

In contrast, Steins;Gate was only adapted as a single anime series in 2011, though the characters in it cross and double-back through a maze of different timelines. But then there was a remarkable twist. In 2015, the anime was repeated on television, but with the last episode (24) dropped, and the end of part 23 switched for an entirely different one. It took the story to a radically different conclusion… which was the launching pad for the 2018 series Steins;Gate 0, based on a follow-up game. It’s hard to imagine any Western TV show being that twisty.

This context suggests that anime creators might be the readiest to follow up the potential of “Bandersnatch.” A many-path production is only possible on a platform like Netflix, which is capable of “cache-ing” multiple possible viewing routes that can be streamed smoothly at the touch of a button. Happily, Netflix is already an established platform for new anime, barely a year after the company’s first big investments in that area. And a multi-choice anime needn’t be anything as technically complex as “Bandersnatch”…

Imagine, for example, a 26-part anime series released in one go on Netflix, all episodes available. Now, let’s imagine it plays a very simple trick. At the end of part 1, the viewer is given two choices about how the story continues. For one route, go to part 2; for the other route, go to part 3. Each of those episodes could offer choices in turn. Of course, each alternate story could only be four or five episodes long; many more choices, and you’d be looking at a show longer than One Piece! But even such a simple format would offer huge potential for gifted creators.

Imagine, for example, a 26-part anime series released in one go on Netflix, all episodes available. Now, let’s imagine it plays a very simple trick. At the end of part 1, the viewer is given two choices about how the story continues. For one route, go to part 2; for the other route, go to part 3. Each of those episodes could offer choices in turn. Of course, each alternate story could only be four or five episodes long; many more choices, and you’d be looking at a show longer than One Piece! But even such a simple format would offer huge potential for gifted creators.

Anime series can already change massively in tone, from slapstick to tragedy to all-out madness, in a way that few other screen works dare. Shows like Tatami Galaxy, Re:Zero and even parts of Evangelion already feel like they’re branching, diverging and exploring multiple choices. It’s no coincidence that at least two of those shows involve time-loops and time-travel, which have become an increasing fixture of twenty-first century anime. So has the “protagonist in another world” scenario, from Sword Art Online to That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime. It’s almost absurdly easy to imagine how that kind of story could work in interactive form – Firetop Mountain plus cute girls.

Before Netflix, the closest thing we had to diverging storylines in films and TV were the “alternate endings” to famous movies that occasionally turned up as DVD extras. One of the best-known is the original end to the 1987 film Fatal Attraction, which makes the whole story radically different from the boiled-bunny version we saw in the West. Perhaps it’s fitting that the original, Madame Butterfly-themed ending, was shown in cinemas… when the film was released in Japan.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Bandersnatch is screening on Netflix.

Andrew Osmond, anime, Bandersnatch, Black Mirror, Charlie Brooker, Japan, Virtual Novels

Alistair

January 9, 2019 8:55 pm

It's interesting you mention the idea of a branching TV anime on Netflix in your articles conclusion as there is a strange hybrid coming to the market shortly. The TV footage from Steins gate has been reinserted with additional sequences into the game instead of the static images as Steins Gate Elite in February. It will be an interesting hybrid on a videogame format but you could recut this with very similar tech to bandersnatch on a streaming format....

andrew osmond

January 11, 2019 11:04 am

Very interesting, thanks for letting me know!