Books: A Brief History of Japan

September 11, 2017 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

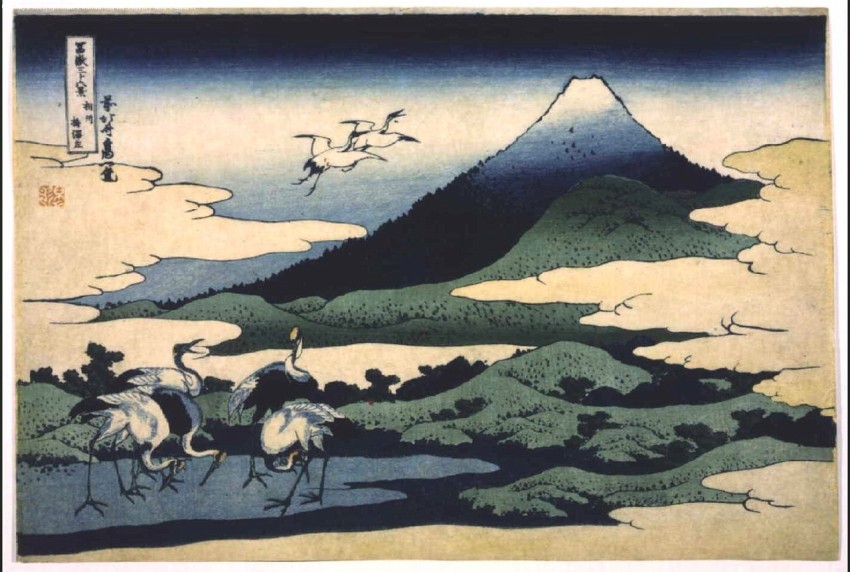

The most common symbols of Japan in the outside world include Mount Fuji, cherry blossom and the film star Toshiro Mifune (of Seven Samurai). In his new book A Brief History of Japan, author Jonathan Clements suggests a less obvious metaphor for the country – the game shogi, Japan’s version of chess. (Shogi has had a resurgence recently, both because of the popular manga March Comes in Like a Lion, and because of a real-life teenage shogi prodigy, Sota Fuji.)

The most common symbols of Japan in the outside world include Mount Fuji, cherry blossom and the film star Toshiro Mifune (of Seven Samurai). In his new book A Brief History of Japan, author Jonathan Clements suggests a less obvious metaphor for the country – the game shogi, Japan’s version of chess. (Shogi has had a resurgence recently, both because of the popular manga March Comes in Like a Lion, and because of a real-life teenage shogi prodigy, Sota Fuji.)

Shogi developed in Japan’s “Warring States” or sengoku period in the 15th and 16th centuries, typified by “reversals, betrayals and flip-flops”. That’s reflected in how shogi’s rules mutated away from chess. Clements writes that the game “transformed, as did so many imports, into something uniquely Japanese. Whereas pieces in traditional chess are considered dead once removed, in shogi they are merely captured and can be restored to the game on the side of their new master.”

Shogi may have reflected the circumstances of medieval Japan, but it seems to predict Japan’s more recent history. What game would be more fitting for a country that sealed itself off from foreign powers from the 17th to mid-19th centuries; then desperately modernised to become one of those powers, ultimately copying the most racist and fascist role-models; then ravaged its Asian neigbours and was pulverised and rebuilt by America; and is now America’s most secure (and secured) ally in East Asia, dotted with US army bases?

But Clements’ book delves back much further than modern Japan and sengoku Japan, into the mists of antiquity. As Clements explains, the surviving records are extremely limited. Japan’s first written histories are both less than 1500 years old, the Kojiki and the Nihongi from the 8th century. Archaeological research is restricted for political reasons, or as Clements puts it, because of a “reality gap between a national mythology that claims the Emperors are all descended from the Sun Goddess and archaeology that suggests they are descended from Korean aristocrats.”

But Clements’ book delves back much further than modern Japan and sengoku Japan, into the mists of antiquity. As Clements explains, the surviving records are extremely limited. Japan’s first written histories are both less than 1500 years old, the Kojiki and the Nihongi from the 8th century. Archaeological research is restricted for political reasons, or as Clements puts it, because of a “reality gap between a national mythology that claims the Emperors are all descended from the Sun Goddess and archaeology that suggests they are descended from Korean aristocrats.”

While China unearthed the Terracotta Army, and Britain has Sutton Hoo, Japan’s Imperial Household “has long been obstructive regarding the excavation of grave mounds that are likely to contain the ancestors of the current Emperor”. For this reason, “there is still no means of accurately examining the (Japanese) period before 700 CE… Japan’s ancient history remains, at least in part, a matter of religious belief that brooks no tampering.”

The first pages of Clements’ book deal with the Japan of mythology. The Kojiki has creation stories, involving the incestuous sibling gods Izanagi (the brother) and Izanami (the sister). The sun goddess Amaterasu is also part of this story cycle, although Clements notes it may be less a cycle than a hodgepodge of tribal stories. The Japanese word for “god”, kami, is close to an Ainu word, kamuy, which refers to tribal totems.

Amaterasu and her delinquent rival Susano’o are both born from the male deity Izanagi, who asexually “sheds gods like dandruff.” The stories of Amaterasu and Susano’o invoke a sacred jewel, mirror and sword. These are Japan’s three Sacred Treasures, still supposedly part of the Emperor’s regalia, though never publicly displayed. The sacred sword has a name that anime fans know – Kusanagi.

The early, perhaps mythical Japanese monarchs did not have to be male, unlike today. The Empress Jingu, who supposedly lived around the third century BCE, is portrayed by the Kojiki as a conquering warrior-queen who triumphed in Korea. The mysterious queen “Himiko” is mentioned in Chinese documents – she reportedly sent emissaries to China – but seems absent from the Japanese records. But she may be the inspiration of the goddess Amaterasu, or Jingu herself.

What is clear is that Japan and the Japanese were transformed by an influx of Korean migrants who crossed into Japan in the early centuries BCE. As they advanced through Japan, so they brought in Chinese writing, “used inexpertly and inaccurately in early attempts to transcribe the words and concepts of the Japanese islands.” They also upheld Confucian values that downgraded women.

These newcomers gradually assimilated the Jomon, Japan’s indigenous people, whom their foes named the “Emishi” (shrimp barbarians). “Talk of the Emishi disappears almost entirely from the historical record by the time Japan becomes more recognisable to the reader, even though they are integral to the country’s formation,” Clements writes. Miyazaki’s fantasy Princess Mononoke imagines that hidden Jomon tribes, and the primal gods at the roots of Japanese animism, survive into the Japan of the 15th or 16th centuries, overlaying different eras of history.

These newcomers gradually assimilated the Jomon, Japan’s indigenous people, whom their foes named the “Emishi” (shrimp barbarians). “Talk of the Emishi disappears almost entirely from the historical record by the time Japan becomes more recognisable to the reader, even though they are integral to the country’s formation,” Clements writes. Miyazaki’s fantasy Princess Mononoke imagines that hidden Jomon tribes, and the primal gods at the roots of Japanese animism, survive into the Japan of the 15th or 16th centuries, overlaying different eras of history.

Historically, animism was overlaid with Buddhism. The religion was imported from China via Korea (specifically the Korean kingdom of Baekje). The main figure associated with integrating Buddhism into Japan was Prince Shotoku at the turn of the 7th century. Shotoku is a historically-grounded figure, an icon of Japan, and a semi-legendary character: “his real-world achievements are difficult to pin down.” He’s the figurehead of not just the establishment of Japanese Buddhism but also “new inventions, sophisticated luxuries and the beginnings of literature.”

Shotoku is credited with organising Japan into a recognisable country. “It was under his tenure that the archipelago stopped being an inefficient, haphazard federation of occasionally hostile states and was transformed into a single unified polity with a reigning sovereign”. Rulers began to be referred to as tenno, “heavenly sovereign”, more often translated as “Emperor”. There was a non-hereditary court and a seventeen-point constitution. Shotoku achieved all this despite never being Emperor himself; rather, he was a Prince Regent, the proverbial power behind the throne.

The country continued to draw heavily on Chinese culture, now through contacts with the ascendant Tang dynasty. The modern Japanese language is often close to Tang-era Mandarin; Japanese temples resemble Tang-era buildings; Japanese people sit on the floor like Tang-era Chinese. “If you want to know how a Tang dynasty princess dressed, look no further than the silks and elaborate coiffure of the Japanese geisha, who emulate the height of Tang fashions.”

From 794, there was a new site for Japan’s capital, modelled on the Chinese city of Chang’an (now Xi’an). Today, the city is no longer Japan’s capital, but it’s called Kyoto, meaning “capital city”. A millennium earlier, it was called Heian, and gave its name to the Heian Period (794-1185), when Japanese literature first flourished. This in turn depended on Japanese writing.

“Heian women – writing for private publication and hence untroubled by the use of abbreviations and slang – wrote their diaries in a cursive, truncated script that threw away the Chinese characters and replaced them with symbols that represented the actual sounds of the Japanese language,” Clements writes. This system became known as hiragana, offering a new way to conjugate Chinese symbols, called kanji in Japan. Meanwhile, katakana, a third writing system, was developed by Japanese monks, originally to explain pronunciations in Buddhist sutras, but today to transcribe foreign words.

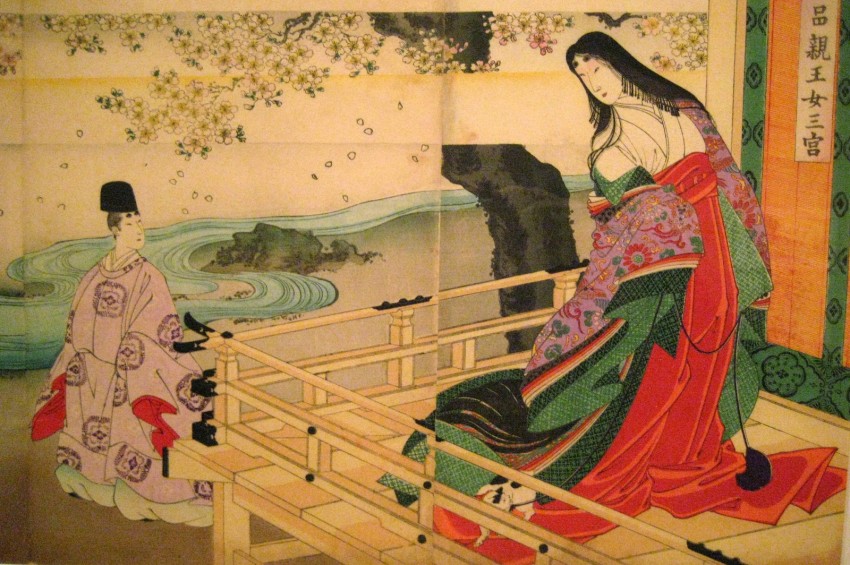

The best-known Heian writing is The Tale of Genji, Japan’s first novel, by the court lady Murasaki Shikibu. However, Clements also highlights her contemporary and frenemy Sei Shonagon. Clements sees both thousand year-old women in contemporary terms. “Shonagon is the hot, flirty one with a ready comeback; Shikibu is the wallflower who thinks of something cleverer, but only on the way home.”

The best-known Heian writing is The Tale of Genji, Japan’s first novel, by the court lady Murasaki Shikibu. However, Clements also highlights her contemporary and frenemy Sei Shonagon. Clements sees both thousand year-old women in contemporary terms. “Shonagon is the hot, flirty one with a ready comeback; Shikibu is the wallflower who thinks of something cleverer, but only on the way home.”

But, Clements adds, “While the diarists wrote of cherry blossoms and snowflakes, in the 700s alone, the Heian court was subject to one enforced mass suicide, two armed rebellions and a conspiracy uncovered in the nick of time.” Feuding families fought, with a ferocity to sate fans of Game of Thrones, which Clements uses as a title for one chapter. Now the powers behind the throne were often retired Emperors, as wily and ruthless as the Livia of I, Claudius.

Unwanted relatives were often banished from the court to fight holdout Emishi tribes. In the field of combat, Chinese tactics were unsuited to Japan mountain terrain. Instead of chariots and metal armour, “the Japanese began to adopt a lighter, more flexible, protection that used interlocking pieces of hardened leather and lacquer, with boxy shoulder guards.”

Exiled from the capital, unwanted imperial relations adopted a name “that played upon both their wish to be seen as loyal retainers of the central court and on the court’s desire to regard them as mere hirelings. They called themselves ‘those who serve’ – the samurai.”

These samurai would fight through many of the insurrections and uprisings of the next centuries. In 1156, there was a battle in Kyoto itself, between samurai supporters of an incumbent emperor and supporters of a retired emperor. Three decades later, the child Emperor Antoku was drowned in the sea by his grandmother as a rival family branch took control. The “original” sword Kusanagi was lost with him. The victorious family members then turned on each other.

By the end of the 12th century, the real power had shifted away from the Emperors to a military governor, the shogun. Officially meant as a temporary antidote for Japan’s turbulence, such men ruled for the next seven centuries. One emperor tried to resist them; the shogunal forces occupied Kyoto and forced him and his family into exile. In the 14th century, another Emperor (Go-Daigo) tried his luck, but only split the Imperial court for a few decades, while the shogun stayed on top.

The 14th century saw the development of Noh theatre as a national art form, bound up with a story out of shonen ai (or shotacon) when a teenage shogun fell in love with a twelve year-old actor. The next century saw another shogun establish the tea ceremony. Clements offers a devil’s advocate argument that “it might reflect the very particular interests of a 15th century bigwig with whom no-one dared argue, like some fearsome, witless despot who decides that the pinnacle of human cuisine is the hot dog.”

The 14th century saw the development of Noh theatre as a national art form, bound up with a story out of shonen ai (or shotacon) when a teenage shogun fell in love with a twelve year-old actor. The next century saw another shogun establish the tea ceremony. Clements offers a devil’s advocate argument that “it might reflect the very particular interests of a 15th century bigwig with whom no-one dared argue, like some fearsome, witless despot who decides that the pinnacle of human cuisine is the hot dog.”

But the same century saw the often-turbulent country plunge into full civil war, the Sengoku period mentioned above. The shoguns’ power seemed to decline as the Emperors’ had before them. Parts of the country become “independent states outside the authority of emperor and shogun, ruled by councils of commoners” (called ikko ikki, “leagues of one mind”.)

The nemesis of the ikko ikki was Japan’s most infamous tyrant, Oda Nobunaga, familiar to anime fans. (Last year’s TV series Drifters presented him as a sympathetic monster voiced by veteran actor Naoya Uchida.) The bloody Nobunaga began a new unification of Japan, followed by two other generals, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu. Ieyasu would be proclaimed a new shogun in 1603, the first of the so-called Tokugawa line.

One of this new shogunate’s first tests was a peasants’ rebellion, reportedly led by a Christian guru. (Clements focused on this rebellion in his previous book Christ’s Samurai, covered here.) “Effusive in its comments about the end of the world and the establishment of a new order, the peasants’ own propaganda sounded all too much like the manifesto for some Christian version of ikko ikki.”

The rebellion was crushed, as part of a campaign to purge Christian influences and foreign influences generally. By the mid-17th century, Japan was a “locked country” (sakoku) where no-one could enter or leave, with very few exceptions. Any citizen with two or more foreign grandparents was exiled from the country. “For two centuries, Japan enjoyed a relative boom time, locked in a time warp that pretended it was the 1630s while the world outside experienced the industrial revolution.”

Clements emphasises that sakoku-era Japan was not simply backward. “The forests were well-managed, the fisheries were abundant, and the farmers benefited from a double-bladed plough and a spike-wheeled potato planter. The cities were thriving, literacy was high, and popular culture was a vibrant whirl.” Kyoto was still the capital, but the cultural centre was the city of Edo where “opinion-formers from every domain served their time.” Edo was also famed for “Edo-mae-zushi,” rice bites seasoned with vinegar, also known as sushi.

Other art-forms developed. Woodblock prints reproduced Hokusai’s art into a wholesale industry; Matsuo Basho stripped poetry down into the 17-beat haiku. In theatre, a scandalous new theatre developed, given a name punning on the words for eccentric, song, dance and prostitute – kabuki. It was a vehicle for topical satire: “Kabuki actors would re-enact the day’s news in skits and adaptations written overnight.” Clements mourns what it would become today, a time-locked antique, “as hidebound and outmoded as the Noh theatre it once supplanted.”

Other art-forms developed. Woodblock prints reproduced Hokusai’s art into a wholesale industry; Matsuo Basho stripped poetry down into the 17-beat haiku. In theatre, a scandalous new theatre developed, given a name punning on the words for eccentric, song, dance and prostitute – kabuki. It was a vehicle for topical satire: “Kabuki actors would re-enact the day’s news in skits and adaptations written overnight.” Clements mourns what it would become today, a time-locked antique, “as hidebound and outmoded as the Noh theatre it once supplanted.”

The last hundred pages of Clements’ book covers Japan’s “modern” history, starting when Matthew Perry’s black ships arrived in 1853 to end sakoku Japan. They triggered a revolution, the Meiji Restoration. By 1869, the shogunate was toppled; the Emperor (or perhaps more accurately, his supporters) was restored to power; and Edo was renamed Tokyo (“East Capital”) and became the official centre of the country.

While many readers will know the narrative of modern Japan, many of the individual episodes will be surprises. Take the visit of the Russian Crown Prince “Nicky”, the future Tsar Nicholas II, to Japan in 1890. During the royal visit, he gained a dragon tattoo in Nagasaki, went wenching in Gion, and fell in love with the country, until he was nearly beheaded by a Japanese assassin.

Fourteen years later, the Tsar would be newly enraged when the Japanese launched a surprise naval attack on Russian ships at China’s Port Arthur. The London Times newspaper hailed Japan’s subterfuge as “an act of daring” – not a description it would apply to the Pearl Harbor attack in the 1940s.

Japan’s catastrophic defeat in 1945 and its occupation by America were depicted in the recent film In This Corner of the World. The Occupation also saw the US authorities forced to rely on war-era Japanese bureacrats. Kishi Nobusuke had been a business tsar in Japan-occupied Manchuria; he’d also conscripted Chinese and Korean slave labour. The Americans injected Nobusuke, who’d been awaiting trial as a Class A war criminal, “back into public life as an antidote to the rising left.” He would form Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party and was briefly the country’s Prime Minister, as is his grandson today – Shinzo Abe.

Japan’s catastrophic defeat in 1945 and its occupation by America were depicted in the recent film In This Corner of the World. The Occupation also saw the US authorities forced to rely on war-era Japanese bureacrats. Kishi Nobusuke had been a business tsar in Japan-occupied Manchuria; he’d also conscripted Chinese and Korean slave labour. The Americans injected Nobusuke, who’d been awaiting trial as a Class A war criminal, “back into public life as an antidote to the rising left.” He would form Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party and was briefly the country’s Prime Minister, as is his grandson today – Shinzo Abe.

The final pages usher in the newest symbols of Japan – manga, otaku and robot toys, along with bullet trains, salarymen and Yukio Mishima (whose farcically botched suicide is described in eye-watering detail). The last chapter opens with a terrifying description of the 2011 tsunami, before depicting other kinds of floods – ghost towns depopulated by falling birth rates and departing youngsters, a situation hinted in the early scenes of the film Your Name.

The last pages also include another of those ironic reverses that might have been expressed on a shogi board. Whereas the 17th-century sakoku edicts banned anyone with two or more foreign grandparents from Japan, today any South American citizen with a single Japanese grandparent is offered incentives to come to the country.

“Japan’s future hence relies upon a great rethinking of attitudes toward foreigners, toward women, and toward families,” Clements concludes. “Straightforward realities in demographics may prove to be as revolutionary and transformative as the Occupation, the Meiji Restoration or the coming of the Black Ships.”

A Brief History of Japan, by Jonathan Clements, is out now from Tuttle.

Leave a Reply