Books: African Samurai

May 20, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

The temple is on fire. The warlord Nobunaga makes his last stand against the henchmen of a traitorous underling. Hearing someone kicking open a side-door, three attacking samurai rush in to execute an escapee, only to face a terrifying, ash-smeared demon.

The temple is on fire. The warlord Nobunaga makes his last stand against the henchmen of a traitorous underling. Hearing someone kicking open a side-door, three attacking samurai rush in to execute an escapee, only to face a terrifying, ash-smeared demon.

“In person they had never seen before a shadow so tall, a man so dark. Nobunaga’s bodyguard stood over them like an adult over children, their helmets barely reaching his chest… [He] clutched a samurai’s sword, its blade already lacquered in blood.”

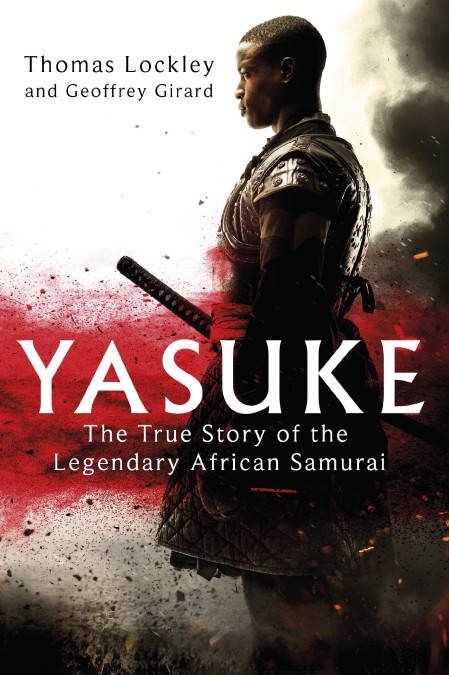

This is Yasuke, the African samurai, introduced in a new book by Thomas Lockley and Geoffrey Girard, ahead of a mooted movie adaptation starring Black Panther’s Chadwick Boseman (pictured). [Time Travel Footnote: this article was written in May 2019, fifteen months before Boseman’s death.]

There is no doubt Yasuke existed – that a black man arrived in Japan in 1579 in the entourage of the Jesuit missionary Alessandro Valignano, and later joined the retinue of the samurai general Oda Nobunaga. However, what we actually know about him could be written on the back of a beer mat. Despite being one of the most prolific correspondents of his era, Valignano never mentioned Yasuke, but he is described in several contemporary accounts by others.

Popular historians live for such moments of intersectionality. Poke around Asian history for long enough, and you will find flashes of striking diversity – the Italian girl buried in a medieval grave in Yangzhou, or the Persian camel drivers celebrated in Tang dynasty porcelain. Reading the 14th-century Travels of ibn Battuta, we find him dropping in on a fellow Muslim in a Chinese harbour town, admiring his “fifty white slaves and as many slave-girls.” You can bet there’s a story, there. An Englishman in samurai Japan, like Will Adams is an entry point for foreign readers, a chance to ground an alien world in a familiar observer.

Popular historians live for such moments of intersectionality. Poke around Asian history for long enough, and you will find flashes of striking diversity – the Italian girl buried in a medieval grave in Yangzhou, or the Persian camel drivers celebrated in Tang dynasty porcelain. Reading the 14th-century Travels of ibn Battuta, we find him dropping in on a fellow Muslim in a Chinese harbour town, admiring his “fifty white slaves and as many slave-girls.” You can bet there’s a story, there. An Englishman in samurai Japan, like Will Adams is an entry point for foreign readers, a chance to ground an alien world in a familiar observer.

The historical Yasuke enjoyed a ringside view of two of the most exciting elements of 16th century Japan. He was there to witness the fanatical height of the “Christian Century”, as southern Japanese warlords converted to the new religion in order to gain access to European artillery, and the inevitable game of thrones that broke out as a result. Passed on, or possibly even sold on to a new master after Valignano’s departure, Yasuke got to witness the rise and fall of Oda Nobunaga, the samurai general brought down in back-stabbing intrigue.

The book’s origin is itself an interesting exercise in historiography. Lockley, solo, wrote an article for a special issue of the Nihon University College of Law journal, detailing what he’d dug up about Yasuke over the years. Within months, this had been parleyed into a contract for a 2017 Japanese-language book, again credited solely to Lockley. It’s only then that Girard arrives, shoved onto the ticket by Lockley’s overseas agents to pep up his narrative, presumably with an eye on the sale of movie rights.

It’s worth noting that Sphere has blessed Yasuke with an awesome, eye-catching cover, an excellent use of resources when one considers the paucity of illustrations. Even though Lockley brags that he and Girard “travelled several thousand miles [sic] together across Japan” to conduct their research, neither of them appears to have packed a camera, and the internal illustrations are often anachronisms two centuries removed from events.

All authors on historical subjects have to pick a point where they are happy to take a little licence. Yasuke is still two steps removed from the blatant fabrication of James Clavell’s Shogun, which has confused generations of Japan scholars by changing everybody’s names (recasting Nobunaga as “Toranaga”, for example), but it still leans on conjecture to a point that strains history to its limit. This is a reasonable decision for a certain kind of book and, I would argue, the perfect register for telling the story of a man whose historical footprint amounts to little more than a listicle. Lockley and Girard have the barest scraps of information about their subject, but rich and textured material about the world around him. This allows them to describe many events at which his presence was likely, and then to drop him in like a samurai variant on Where’s Wally.

So we know, in detail, that the Jesuits in Japan would put on mystery plays at Christmas, and indeed we have a glorious eye-witness account of a Japanese crowd’s reaction to the story of Adam and Eve. The authors extrapolate that it is very likely that at some point there was also a Nativity play, and if there were, someone would need to play Balthasar, the black member of the Three Wise Men, and that if they needed someone to play him, then wouldn’t Yasuke have been a good choice? This is gold-standard reasoning for a historical novelist, and I urge the reader to approach Yasuke in that frame of mind, as a work of fiction grounded in superb research. Yasuke remains a cipher in the book that bears his name, but he is a wonderful means of viewing a fascinating, vibrant period in Japanese history.

From this perspective, Yasuke is a marvel, and catnip for a canny film producer. As a popular account of Japan’s Christian Century it is certainly going to create a lot of new interest, although as a work of actual history, it is riddled with speculative brinkmanship.

“You are my black warrior,” Nobunaga said, reaching up to grip Yasuke’s shoulder. “The demon who will ride beside me into battle, the dark angel who protects me and my family up in my home.”

This is not the “true story” proclaimed on the cover. Amazon, possibly following the publisher’s own metadata, is filing this book as History, but it is what TV people call “recon” – historical reconstruction, a dramatisation of possible events, and not necessarily drawing on the most modern or accurate scholarship.

An account of stories the Jesuits might have heard about ninja, for example, is rooted not in the historical record, but in the claims of a bunch of twentieth century fabulists, which the authors have accepted at face-value. I wouldn’t mind – I might have done much the same thing if writing a fictional account of the 16th century – but their own references include Stephen Turnbull’s Ninja: Unmasking the Myth, which cites chapter and verse on what the ninja most definitely weren’t.

An account of stories the Jesuits might have heard about ninja, for example, is rooted not in the historical record, but in the claims of a bunch of twentieth century fabulists, which the authors have accepted at face-value. I wouldn’t mind – I might have done much the same thing if writing a fictional account of the 16th century – but their own references include Stephen Turnbull’s Ninja: Unmasking the Myth, which cites chapter and verse on what the ninja most definitely weren’t.

The authors can sometimes be a little too ready to proclaim cases closed and mysteries solved with glib assurance – fine for novelists, frustrating for historians. Although the Japanese edition of Lockley’s book offered four possible places of origin for Yasuke, the English version, with no new evidence, gives him a birthplace and a backstory, loaded with many a probably and a might-have-been.

The book ends in a veritable pillow fight of padding. Yasuke is not mentioned again after the battle of Okitanawate (itself an amazing story), so he might have died there. Or he might not have. And if he didn’t, then maybe he was one of the other black men mentioned elsewhere in the historical record? Lockley and Girard suggest, for example, that he might have ended up in something like the Black Guard, the division of Moorish and African soldiers who served the Chinese pirate-smuggler Zheng Zhilong. Except, as they concede themselves, Zheng wasn’t born until 1604, by which time Yasuke ought to have already been in his fifties.

That alone ought to be enough to discount it, but since the authors go on for four pages about it on my Kindle, I’ll offer some facts of my own. The authors claim that the Black Guard died defending Zheng against the Manchus, whereas in fact a sizeable number of them remained in the service of his famous son, Coxinga. In fact, they remained a fixture for a whole generation – a “Captain Moor Ongkun” was one of Coxinga’s men, exchanged as a hostage during parleys with the Dutch in 1661, and when Coxinga’s widow ordered the murder of his grandson on Taiwan in 1681, the unfortunate boy was “by the black slaves barbarously strangled.” I’m not saying that a centenarian Yasuke was present at this incident – just that the further we travel from the tight focus of this movie-compatible outline, the more the history fogs up.

None of the above should detract in any way from the authors’ broader achievement, of telling a story that gives this jaded historian the same sort of thrill he got as a ten-year-old boy seeing Shogun for the first time. It took me a long time to stop referring to the victor as “Toranaga” instead of Nobunaga, but it didn’t do me any harm in the long-term. This is a true story. But a lot of it isn’t true.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Christ’s Samurai: The True Story of the Shimabara Rebellion. Yasuke: The True Story of the Legendary African Samurai, is published in the UK by Sphere.

Leave a Reply