Books: Animated Encounters

March 7, 2019 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

In her new book, Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation 1940s-1970s, Daisy Yan Du argues against the way that Chinese animation wants to see itself, so often presented as an entirely local, inwardly focussed realm that pays no heed to foreign markets. Particularly in the period under study, you might be forgiven for thinking that Chinese animation was limited largely to curiosities at a few Eastern bloc film festivals, as well as dour propaganda cartoons. But Du swiftly wins the reader over with her presentation of a rich field for collaboration between artists from multiple countries, along with surprising accounts of foreign investment and influence.

In her new book, Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation 1940s-1970s, Daisy Yan Du argues against the way that Chinese animation wants to see itself, so often presented as an entirely local, inwardly focussed realm that pays no heed to foreign markets. Particularly in the period under study, you might be forgiven for thinking that Chinese animation was limited largely to curiosities at a few Eastern bloc film festivals, as well as dour propaganda cartoons. But Du swiftly wins the reader over with her presentation of a rich field for collaboration between artists from multiple countries, along with surprising accounts of foreign investment and influence.

In the case of Japan’s Momotaro, Sacred Sailors, for example, Du points out that this notorious wartime feature not only produced the seed-bed of the 1950s animation business in Japan, but had far-ranging effects elsewhere. Among its animators, Tadahito Mochinaga fled for China, where he kick-started the Chinese animation industry, while Kim Yong-hwan returned to his own native country and was similarly influential in the post-war animation industry of South Korea.

Du recounts a cringe-worthy moment at the Venice International Film Festival in 1956, when a win for the “first Chinese colour animated film”, Why is the Crow Black?, was compromised by the jury’s assumption that the cartoon was a Soviet production. It’s this embarrassment, threatening to destroy Chinese animation’s marketing capital as a Chinese artefact, that supposedly propelled the industry into ever more desperate attempts to produce undeniably Chinese-looking works – fighting the “stateless” appearance of American (and, she argues, Japanese) films with a relentless concentration on Chinese subjects, Chinese styles and Chinese stories… whatever that might mean. Du points out that, in transnational terms, that often meant “essentializing” Chinese culture, over-simplifying it in an attempt to let foreign audiences think that they have had an authentic Chinese experience. This debate is common to film industries in search of an audience overseas, but in China it must face the additional hurdle of appeasing the authorities, whose definition of what “Chinese” is cannot be guaranteed.

Du recounts a cringe-worthy moment at the Venice International Film Festival in 1956, when a win for the “first Chinese colour animated film”, Why is the Crow Black?, was compromised by the jury’s assumption that the cartoon was a Soviet production. It’s this embarrassment, threatening to destroy Chinese animation’s marketing capital as a Chinese artefact, that supposedly propelled the industry into ever more desperate attempts to produce undeniably Chinese-looking works – fighting the “stateless” appearance of American (and, she argues, Japanese) films with a relentless concentration on Chinese subjects, Chinese styles and Chinese stories… whatever that might mean. Du points out that, in transnational terms, that often meant “essentializing” Chinese culture, over-simplifying it in an attempt to let foreign audiences think that they have had an authentic Chinese experience. This debate is common to film industries in search of an audience overseas, but in China it must face the additional hurdle of appeasing the authorities, whose definition of what “Chinese” is cannot be guaranteed.

This helps explain why the thinkers and plotters of the Chinese animation world so often make big promises about originality, only to crank out yet another remake of Monkey. At a deeper level, it unpacks into considerations of what a “Chinese” subject actually might be. It might be an excuse to, say, celebrate the diversity of China’s 55 ethnic minorities, but going into production on anything beyond the most anodyne of subjects is a political minefield. Du argues that such a concentration on traditional appearances has even compromised scholarship on Chinese film, encouraging academics and film festival programmers to focus on stuff like Big Fish and Begonia, that looks appropriately ethnic, rather than the more contemporary feel of something like Flavors of Youth, heavily influenced by contemporary anime, and set in modern, urban spaces. In her words, “Chinese animation thus remains stubbornly and overly national,” a problem she traces back to the post-war era, when production was largely in the hands of a single studio, funded by government stipends that did not consider market forces.

Du’s concentration on Chinese animation in an international context is a rewarding account not only of films released, but of unexpected influences and projects that never happened. She regards China’s first animated feature, the Wan brothers’ Monkey King fable Princess Iron Fan (1941), for example, as “far more influential in wartime Japan than in wartime China,” but also reports that when Japanese animators came to Shanghai in 1988 looking for subcontractors on the Saiyuki TV anime, the Shanghai Animation Studio refused to work on it, because the Japanese version of the legend of the Monkey King deviated too far from acceptable norms. Buried in her footnotes is an equally interesting allegation: that Fuwa (2007), a series about the adventures of the Beijing Olympic mascots, was subject to accusations of plagiarism from the anime Sergeant Frog, but such discussion was swiftly suppressed. Meanwhile, Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, a ubiquitous cartoon series, running in China for the last fourteen years, “was regarded as unsuitable for export because it was not Chinese enough.”

I would quibble with a few of these assertions, not the least because there are numerous incidents of Chinese animation companies happily working on productions that are so “non-Chinese” that they were later banned in China as dangerous foreign imports. And in the case of Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, I am not all that sure that the Chinese could even give it away, let alone sell it abroad. But Du’s citations are rock-solid – if someone is being economical with the truth, it is not her, but the sources she is diligently quoting.

Du repeatedly and successfully makes the point that Chinese animation does not exist in a Chinese-only environment, even if it often pretends that it does. She rolls this idea right back to the very beginning, pointing out that the very first Chinese cartoon, Uproar in an Art Studio (1926) was made for a production company founded in New York by a Chinese-American, Mei Xuechou, himself trained by the Fleischer brothers. She traces the impetus for the production of Princess Iron Fan directly to the release of Disney’s Snow White in Shanghai in 1938, and notes that Princess Iron Fan itself would have been impossible without “financial capital and film stock from Japan.”

Du begins with the vibrant ferment of occupied Shanghai, where the Japanese put one of their own, Nagamasa Kawakita, in charge of local film production, into which he invested substantial amounts of his own money. He threw himself into making innocuous costume dramas designed to walk a middle ground between China and Japan, although his plans were thwarted at a screening of the live-action Mulan Joins the Army (1939), when protesters denounced the film as propaganda, trashed the cinema and burned the print. Du dives deep into the work of the Wan brothers, not merely in terms of their animation output, but in terms of their animated contributions to films filed as “live-action”, including special-effects work in early wuxia, and bouncing-ball subtitles for singalong scenes.

Du begins with the vibrant ferment of occupied Shanghai, where the Japanese put one of their own, Nagamasa Kawakita, in charge of local film production, into which he invested substantial amounts of his own money. He threw himself into making innocuous costume dramas designed to walk a middle ground between China and Japan, although his plans were thwarted at a screening of the live-action Mulan Joins the Army (1939), when protesters denounced the film as propaganda, trashed the cinema and burned the print. Du dives deep into the work of the Wan brothers, not merely in terms of their animation output, but in terms of their animated contributions to films filed as “live-action”, including special-effects work in early wuxia, and bouncing-ball subtitles for singalong scenes.

Princess Iron Fan, in turn, inspired the Japanese Navy to fund Momotaro’s Sea Eagles (1943), released in Shanghai under the title The Flying Prince Bombs Pearl Harbor. Contrary to Japanese sources, which imply the film was an international hit, Du calls it a box-office bomb in Shanghai, but regardless, without Princess Iron Fan, there would have been no Sea Eagles, and without Sea Eagles, there would have been no Sacred Sailors. And depending on which version of Osamu Tezuka’s story you believe, either Princess Iron Fan or Sacred Sailors made him want to become an animator, which changed Japanese animation forever.

Du points to to the constant returns to Princess Iron Fan and the Monkey King in Tezuka’s own later work. She also quotes extensively from Tezuka’s own claims to have been inspired by Princess Iron Fan. In fact, she has him bragging to an audience of Chinese animators that Princess Iron Fan changed his life, as late as 1981, just two years before the rediscovery of Sacred Sailors prompted him to claim otherwise, and doing so again in 1989… all of which suggests that his claims for the importance of Sacred Sailors in his work were a brief and convenient publicity stunt.

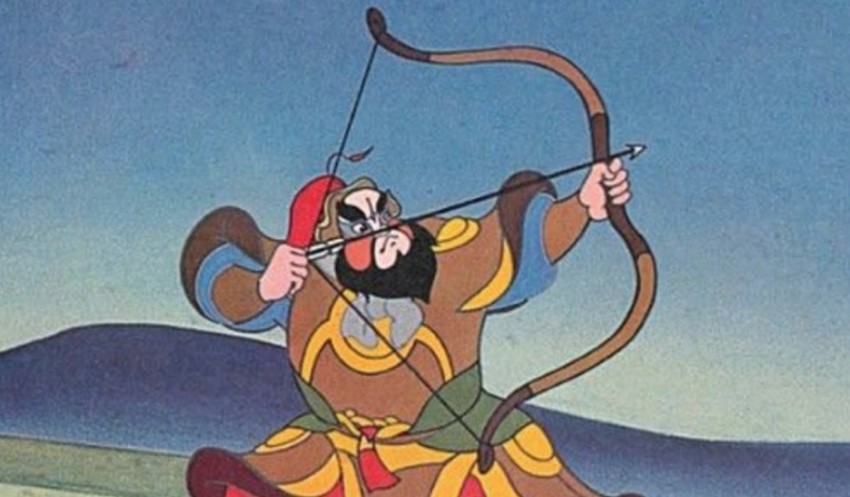

The most obvious figure in the history of Sino-Japanese animation, of course, is Tadahito Mochinaga, the Japanese artist who ran for Manchuria after the production of Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (pictured), and became instrumental in the world of Chinese animation, before returning to Japan, struggling to make a living in stop-motion, and eventually supplying Rankin-Bass with their TV movies like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. He’s not quite as “ignored or downplayed” in China as Du suggests – every visitor to the film museum in Changchun is confronted with his story and his propaganda film Turtle in the Jar, which runs on a constant loop as the first exhibit inside the door – but in Du’s text he is notable not only for bringing animation technology to China, but for returning to Japan with technical know-how from Chinese puppet animation. She devotes an entire chapter to his work in both China and Japan, generating the most comprehensive account yet available in the English language. Du’s story is thick with detail, outlining not only the plots and themes of Mochinaga’s films, but also magical moments from his life. In one telling incident, he realises that the animation gear has been left off the Communist Party truck relocating the film personnel from Changchun. Mochinaga plaintively asks if he is not going, only to be told that nobody knows how to dismantle the rostrum camera, and that everybody is waiting for him to do it.

The most obvious figure in the history of Sino-Japanese animation, of course, is Tadahito Mochinaga, the Japanese artist who ran for Manchuria after the production of Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (pictured), and became instrumental in the world of Chinese animation, before returning to Japan, struggling to make a living in stop-motion, and eventually supplying Rankin-Bass with their TV movies like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. He’s not quite as “ignored or downplayed” in China as Du suggests – every visitor to the film museum in Changchun is confronted with his story and his propaganda film Turtle in the Jar, which runs on a constant loop as the first exhibit inside the door – but in Du’s text he is notable not only for bringing animation technology to China, but for returning to Japan with technical know-how from Chinese puppet animation. She devotes an entire chapter to his work in both China and Japan, generating the most comprehensive account yet available in the English language. Du’s story is thick with detail, outlining not only the plots and themes of Mochinaga’s films, but also magical moments from his life. In one telling incident, he realises that the animation gear has been left off the Communist Party truck relocating the film personnel from Changchun. Mochinaga plaintively asks if he is not going, only to be told that nobody knows how to dismantle the rostrum camera, and that everybody is waiting for him to do it.

Du’s narrative is just as exciting in the post-war period, none more so when she gets forensic with Why is the Crow Black? In fact, she points out, contrary to the story repeated by many accounts (including earlier in this very review), it didn’t actually win anything in Venice, and even if it had done, it competed in 1956, when the more “traditional” film, The Conceited General, was already nearing completion. In other words, The Conceited General can’t possibly have gone into production as a result of the reception of Why is the Crow Black?, which ruins much of the narrative of the traditionalist lobby.

Unlike earlier books on Chinese animation, which often treat the period with a merely descriptive focus, Du drills down to who-did-what. She dismisses both the film-studies habit of attributing ownership of a film to its director, and also the Mao-era penchant for pretending that everything was a collective effort, in favour of an exactitude sure to delight any sakuga fan. In the case of the iconic Little Tadpoles in Search of Mama, for example, she has done enough legwork in phone calls and interviews to be able to say: “the chickens were drawn by Tang Cheng and Pu Jiaxiang, the golden shrimp by Wu Qiang and Dai Tielang, and the tadpoles by Lin Wenxiao.”

Du’s book comes to an end in the 1970s, shortly before a new flowering of Chinese animation, and the opening up of the country to foreign money and exports. You might think that this was a bit of an easy grade, scrambling for the finish just before she has to grapple with the lack of transnational influences in a more open era. But she applies her methods just as readily and persuasively to the new era, chronicling a massive brain-drain of Chinese animators (maybe 50% of the working population) leaving for better opportunities abroad, and thereby contributing to the success of “foreign” cartoons, as well as a large group of Chinese animators who disappear into subcontracting for the Japanese. She details the true impact of 1980s Chinese broadcasts of Astro Boy, thereby revealing a hidden set of influences on “Chinese” animation from Japanese sources. “Rather than a closure or destination,” she writes, “this book is an opening, a point of departure for many academic journeys ahead.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History and Sacred Sailors: The Life and Work of Seo Mitsuyo. Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation 1940s-1970s is out now from Hawaii University Press.

Leave a Reply