Books: Behind the Kaiju Curtain

November 21, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

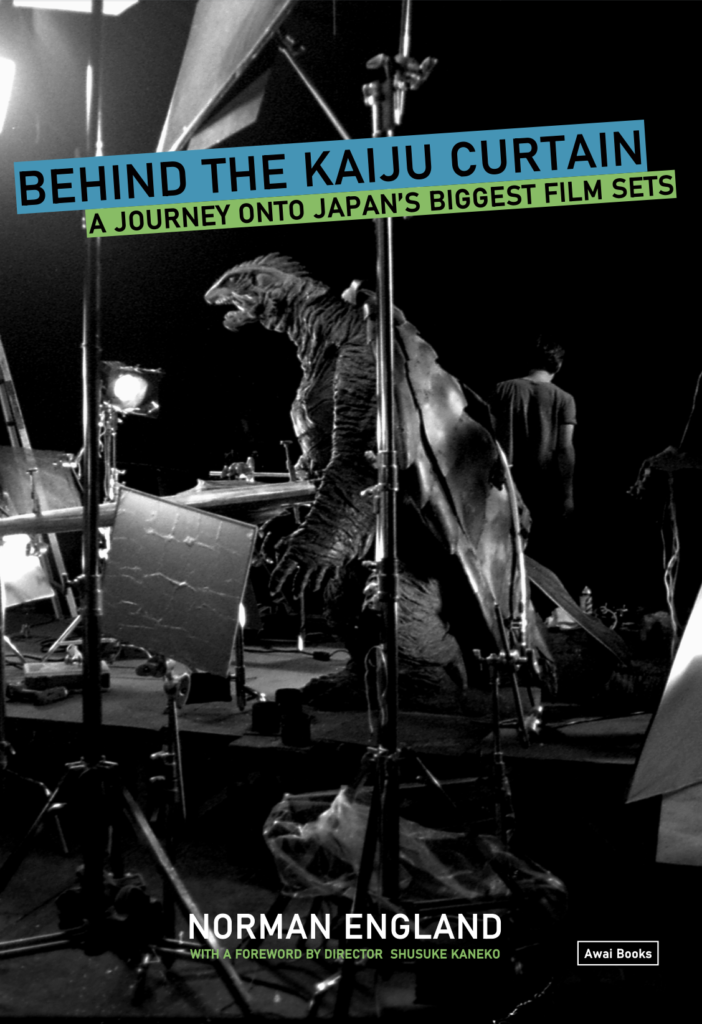

Despite the title, which immediately and perhaps unjustly evokes Jasper Sharp’s magisterial Behind the Pink Curtain, Norman England’s Behind the Kaiju Curtain: A Journey onto Japan’s Biggest Film Sets is not an exhaustive account of an entire genre. Instead, it is a very personal snapshot of one man’s interaction with the Japanese monster-movie world at the turn of the century, in which he found himself briefly part of what might be best described as a Japanese director’s entourage. The author begins as little more than a movie nerd among the hordes of English teachers in late twentieth-century Japan, suddenly catapulted into film production when someone at CAPCOM reads his liner notes for a zombie movie, and decides he’s the ideal guy to ride shotgun on George Romero, in Japan to shoot a commercial for the second Resident Evil game.

Yes, a commercial. God bless CAPCOM, who handed Romero a $1.5 million dollar budget for 30 seconds, which he himself describes as “the most money I’ve had on a second-by-second basis.” But it’s also a game-changer for England, whose presence as the director’s right-hand man in Japan leads to him being tapped on the shoulder by Fangoria to be their Japan correspondent.

England is touchingly forthright regarding his own initial ineptitude, actively wondering, as the director Shusuke Kaneko delivers a series of bland, rote replies to his questions, if he is really cut out to be a journalist. But England is already ticking the right boxes, zooming in not to whatever guff Kaneko is talking about on the PR trail for some monster movie, but about the ramshackle appearance of the Nikkatsu staff canteen, where “deeply wrinkled women, their heads topped with white bonnets, dish out dark brown curry from industrial-sized aluminium pots to a line of tired-looking men.” The misfiring interview with Kaneko, meanwhile, turns out to be a double bluff. Learning on the fly, England discovers what it is that really animates his interviewee, pivoting mid-interview to questions that allow Kaneko to reach into his toolkit as a former teacher and educate the foreign listener about the Japanese film industry. It is a touching and all-too-real insider’s view, not of Japanese movie-making, but of the interviewer’s art. Twenty years on, Kaneko provides the introduction for this book, and still fondly recalls that on their first meeting “I also taught him about Japanese history.”

I’m spending so much time on these early scenes because of the way they evoke England’s particular style, in which he often comes across less as a gimlet-eyed newshound with a notebook, and more like an affable man in a pub, buttonholing an audience of fanboys with a pint of Real Ale in front of him. England never quite leaves his nerdy days behind him, and even as he upgrades to The Japan Times, he sometimes seems to drift off in little reveries of his own, the words of an actress fading into comedy static while he admires her boots, or her coat, or her hair. But this a man who can instead describe the haptic sensation of climbing into a Godzilla suit – the tightness of the legs, the awkardness of the feet, the positioning of the chin-guard. He grills sweet potatoes with Kenpachi Satsuma, the rumble-voiced Godzilla actor, and is fantastically obtuse with the actress Ayako Fujitani, turning off his tape recorder and warning her that unless she comes up with some better answers, he will have to throw away his interview. I mean: much respect for standing up to a reticent Japanese thespian, but do you really want to get into a fight with Steven Seagal’s daughter? Fortunately, she seems to forgive him soon enough, and before long, they are hobnobbing with the Japanese cast after-hours.

All the while, England provides valuable testimony of what it was like to be in the Japanese movie world of 1997-2001. On being handed an Access All Areas pass to the set of Gamera 3, he quips “I’M WITH THE BAND!” to an unsmiling Daiei PR man… it is a moment of Alan Partridge cringe-worthiness, from a writer determined to chronicle his own shortcomings with humility and good humour. The same flunky soon returns with hand-waving anger, shouting across the set because England has picked up a packed lunch reserved for the crew, leading the director to intervene and England to acquire a new nemesis. But while metadata tagging might inevitably associate this book with making-ofs and movie histories, that would be doing it a disservice. It belongs much more firmly among gaijin memoirs like Ian Buruma’s A Tokyo Romance, undoubtedly revealing much about Japan, but also dwelling on the narrator’s personal journey and development. England’s diary entry for 20th April 2001, for example, is not about the costume fitting for the new Godzilla suit, but the fact that he can’t actually be there, because he has to put in extra hours at the English school. He makes up for it the following day with an in-depth account, but it is important to understand that England himself is just as important a character in these memoirs as the rubber monsters that will bring in most of the curious readers.

The main chapters of the book deal with England’s observations during the filming of Gamera 3: Revenge of Iris, Godzilla 2000 and Godzilla vs Megaguirus. Some of them previously appeared as studio-sanctioned making-ofs or Fangoria articles, and they are topped here by a 150-page epic taking Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack from pre-production, shooting, post-production (England incisively distinguishes between “SFX” shot in-camera on set, and “VFX” which are added in post), and release. In other words, much as Steve Alpert’s much-praised Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man comes to a halt in the early noughties, England’s diary of Japanese movie-making finishes with a Godzilla press call on 15th December 2001.

Although England stayed in the Japanese film world thereafter, and hints at experiences as-yet untold in the noughties and beyond, he bows out in 2001, glossing over his further adventures in a swift epilogue. England the bumptious gaijin transforms into a living culture clash, not only chronicling an excruciating catalogue of faux pas, but also the oddities of Japanese PR through foreign eyes – he is, for example, comically aghast at what passes for a “special event” in Japan, where fans are expected to shell out £100 for a “sneak preview” and a jigsaw. In a world where Japanese production executives are notoriously thin-skinned about absolutely everything, I almost spat out my coffee imagining how one of them might react to the revelation that the bento boxes supplied by Toho apparently all “suck ass,” even if England does put such a review in the mouth of an unidentifiable crewmember.

Behind the Kaiju Curtain lacks an index (at least in the PDF I was sent for review) – a shame because it is riddled with titbits of data that other writers on Japanese cinema are sure to mine for their own works. England’s observations on film-making argot (people say “good morning” to each other, even at night), on the hierarchies and customs of a live set, of the camaraderie and dramas of cast and crew, even down to the jocular trash-talk that arises as the Godzilla and Ghidorah performers get into their suits, has a value belied by his clownish, self-deprecating humour. He doesn’t merely begin the book by clambering inside a Gozilla suit; nearly two hundred pages later, he reveals that he has actually got stuck inside it – a fittingly hapless situation for England’s cheerful memoir of a particular period in Japanese movie-making.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Behind the Kaiju Curtain, by Norman England, is released by Awai Books.

Leave a Reply