Books: Branding Japanese Food

May 24, 2021 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

In 2013, the Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe took the remarkable step of appearing on YouTube to talk about Japanese food. He was addressing the nation, and the world, about Japan’s unique culinary tradition, or washoku, as part of an effort to get it rated as one of UNESCO’s treasures of intangible cultural heritage. But as authors Katarzyna Cwiertka and Miho Yasuhara point out in their book Branding Japanese Food, Abe was spinning a ridiculous yarn. Japan had been prompted, somewhat belatedly, into bigging up its classier cuisine after French food had received a UNESCO nod.

Here’s the thing: washoku cuisine is about as “traditional” as a fish finger. The word doesn’t even turn up in Japanese media until the modern era, and even then, initially only as some vague “local” cuisine, as distinguished from all the foreign food that came pouring in after the Meiji Restoration. Draped in the Japanese flag, with koto music plinky-plonking in the background, Abe’s plea came only weeks after his own culture ministry had recognised washoku as an intangible treasure. Far from being an ancient and noble tradition, the authors write, it was “…a mythical phenomenon that had not really existed prior to the twentieth century.” Abe waxed lyrical about ancient traditions and balanced dining, pointing to the soup-and-three-sides of an ancient Japanese meal, but neglected to mention that hardly anyone among the ancient Japanese would have recognised it.

There are all sorts of politics in play here, and the authors tell an intriguing tale about the scramble for UNESCO attention. Abe might have been more persuasive if he had talked referred to it as kaiseki cuisine, but his policy wonks had advised him that kaiseki carried with it too many upper-class associations. Across the Tsushima Strait, Korean courtly food had just been knocked back from its UNESCO application for that very reason, so Abe needed to pretend that washoku was a thing, and had always been a thing, and would be recognised by the man in the street, not merely a medieval prince.

When even the Japanese government can’t be trusted to define what Japanese food actually is, Cwiertka and Yasuhara have oodles of fun investigating some of its forgotten byways. They are particularly interested in another kind of Japanese food, the meibutsu or “local delicacies” that cropped up all along the old access roads to and from the Shogun’s city of Edo. Many embassies from samurai domains were obliged to march up and down the country for periodic audiences with the Shogun. This soon led to the setting up of “tea towns” – roadside food outlets clamouring for the passing trade, usually with a spurious claim for some sort of unique local product. Come and try our Kamakura Lobster! You haven’t lived until you’ve tasted a Tama Trout! You can’t come to Enoshima without trying the abalone! Entirely at odds with what the locals were actually eating, these wheeler-dealers helped create much of the supposed heritage of modern Japanese foods, particularly after the end of the samurai era and the rise of the train network caused many of them to relocate to station concourses.

Nagasaki got sponge-cake because the Portuguese brought in sugar-cane from the South China Seas. Candies in general only became widespread in the days of empire, when Japan’s acquisition of Taiwan brought access to sugar-cane plantations. Until then, sugar cost five times as much as rice, and was hence used only sparingly. And as for rice, until the twentieth century, it was only eaten on special occasions, being much more useful in the samurai era as a form of currency, since it’s what samurai retainers were paid in.

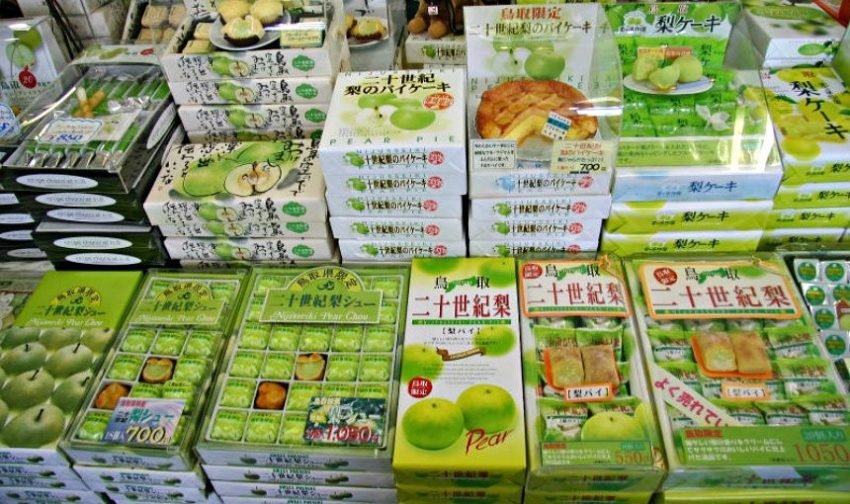

Go anywhere in modern Japan, and there will be some kind of local product that the dutiful traveller feels obliged to pick up. I was in Nagasaki so I got you this sponge cake. I was in Nagoya so I got you this biscuit. You can tell I’ve been to Aomori because I’ve got a bag of apples. Showily packaged, and priced at discrete levels of how-much-you-care-about-your-aunt, they are perfectly judged units of obligation, a little memento for someone you need to impress or your envious work colleagues, handily consumable and hence not cluttering up anyone’s mantlepiece for the next ten years.

Cwiertka and Yasuhara relate much of this to the Discover Japan campaign, an incredibly influential series of marketing initiatives designed to get Japanese people making more use of their rail network after the initial flurry of Tokyo Olympics and Osaka Expo travellers died down in the early 1970s. Discover Japan earnestly tried to find something unique and visitable about every corner of the country, and over time this led to the concoction of a bunch of ersatz specialities, including an omelette named for the Dark-Age witch-queen Himiko, and cream cookies with a picture of ptarmigan on them, from a place where you can see a ptarmigan sometimes. Many of these delicacies in our own era reflect an assumption that the most likely tourist is female – with off-duty office ladies and covens of empty-nest housewives roaming Japan in packs, searching for cocktails, sundaes and noodle dishes they can brag about on Instagram.

Foods and local dishes can be a welcome window into history, attached to folklore or some sort of interesting bit of trivia. Staying at an old-fashioned inn in Shimabara, I was once served guzoni, a local dish said to replicate the grim, spartan broth that Christians under siege at Hara Castle scraped together from seaweed and shellfish. Outside the navy base at Yokosuka, I was nearly defeated by a military-grade curry, introduced, it was said, by the Royal Navy. Many such oddities, however, are more like “invented traditions”, recent initiatives designed to give local hawkers something to sell to tourists. The authors note, for example, that Atsumori Noodles might be named for a famous samurai killed at the battle of Ichinotani, but actually have sod-all to do with him, having been dreamt up by a couple of café owners near the battle site.

The authors take the fads and trends right up to the present-day, with a new emphasis on local foods not for their historical connection, but for points-scoring in sustainability and seasonality. I went to Matsushima so I got their spring seaweed. I went to Hokkaido, so I had to try tamago kake gohan… no, wait, that’s not a Hokkaido delicacy, that’s just something someone eats in the anime Silver Spoon. Anime itself, of course, has created a series of food-tourism dishes all of its own, from the furikake rice in Food Wars, to the ham noodles of Ponyo. There are even places where you can order Calcifer’s Breakfast from Howl’s Moving Castle, even though that’s basically just eggs and bacon.

Jonathan Clements is the author of The Emperor’s Feast: A History of China in Twelve Meals. Branding Japanese Food by Katarzyna Cwiertka and Miho Yasuhara is published by the University of Hawaii Press.

Leave a Reply