Books: Chinese Animation… Again

December 16, 2017 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

As its subtitle suggests, Wu Weihua’s book Chinese Animation: Creative Industries and Digital Culture delves into two specific elements of cartoons in China – the effects of disruptive transitions on a struggling business, and the massive transformations wrought by computers. Both these areas are under-represented in previous studies of the medium, and Wu draws upon his own 2006 doctoral dissertation for a concise and thought-provoking examination, rich in citation and commentary.

As its subtitle suggests, Wu Weihua’s book Chinese Animation: Creative Industries and Digital Culture delves into two specific elements of cartoons in China – the effects of disruptive transitions on a struggling business, and the massive transformations wrought by computers. Both these areas are under-represented in previous studies of the medium, and Wu draws upon his own 2006 doctoral dissertation for a concise and thought-provoking examination, rich in citation and commentary.

An early concentration on theory opens up some interesting areas. Just as Mao-era literati tried to concoct a theory of what science fiction should be, Eileen Chang’s 1993 “Regarding the Future of Cartoons” pushed for the consideration of animation as “a major representative form of Chinese film.” Animation scholars proclaiming it’s not just for kids any more is nothing new, but Chang pointed out that it never was “just for kids”, and predicted, rather hopefully, that Chinese audiences would soon tire of Disney propaganda and embrace more local cultural products. But Wu is entertainingly scathing about the form that subsequent criticism took, dismissing the books written on Chinese animation in China as “discursively similar expressions of one-dimensional cultural memory”, and berating a recent history of Chinese film for failing to regard animation as worthy of inclusion.

An early concentration on theory opens up some interesting areas. Just as Mao-era literati tried to concoct a theory of what science fiction should be, Eileen Chang’s 1993 “Regarding the Future of Cartoons” pushed for the consideration of animation as “a major representative form of Chinese film.” Animation scholars proclaiming it’s not just for kids any more is nothing new, but Chang pointed out that it never was “just for kids”, and predicted, rather hopefully, that Chinese audiences would soon tire of Disney propaganda and embrace more local cultural products. But Wu is entertainingly scathing about the form that subsequent criticism took, dismissing the books written on Chinese animation in China as “discursively similar expressions of one-dimensional cultural memory”, and berating a recent history of Chinese film for failing to regard animation as worthy of inclusion.

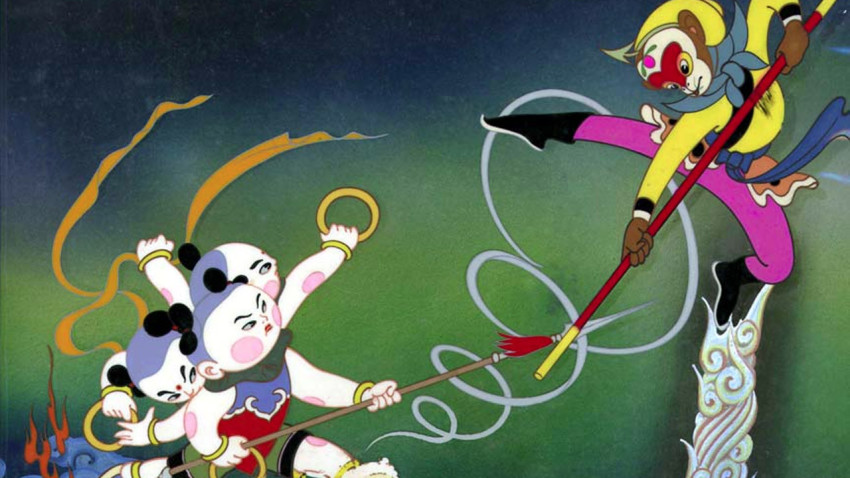

Wu is keen on minzu animation, which he qualifies with a bunch of political criteria, but which amounts to a style deriving from folk arts. Certainly, anyone with a passing acquaintance with Chinese animation will immediately recall many examples – cartoons alluding to watercolour brushwork, or that evoke shadow puppetry, or even the powerful influence of Beijing opera on The Conceited General and Havoc in Heaven. He maintains his focus on such a “Chinese School”, because it is sure to be a harbinger of the anti-Disney movement that Eileen Chang was hoping to see. Later on, Wu points out the inherent contradiction in the likes of The Lotus Lantern, which is undeniably a Chinese cultural product, but also very clearly inspired by Disney features. He relates this to the author Lu Xun’s concept of “grabbism”, as developing societies snatch what they can from the markets they are trying to supplant.

Characterising “Chinese animation” as animation that looks Chinese and comes from China, however, ignores the work that is conducted below the line on foreign productions. Wu himself acknowledges this, and his response would surely be that there is little cultural value or artistic argument to be had over the colouring in Ghost in the Shell or the graphics on Kung Fu Panda 3. Or, if there is, it is something to be discussed at an industrial or financial level, a world away from culture wars and political propaganda.

Wu dedicates an entire chapter to the cultural impact of imported animation, beginning with the relatively obscure anime feature Taro the Dragon Boy in 1979 (pictured), and followed swiftly by Astro Boy on television in 1982 (I presume that this was the 1980 colour remake, not Tezuka’s 1963 original), and a flood of both Japanese and American cartoons. Astro Boy, in particular, rode the spirit of the times, encapsulating the pro-science message of the Deng Xiaoping era, when Chinese science fiction experienced a brief boom in futurist speculation. Again, to split hairs from an industrial perspective, I would point out that from 1979 onwards, many of the “foreign” cartoons coming into China were also partly made there, although as before, this does not necessarily detract from the critical arguments that Wu is repeating.

Wu dedicates an entire chapter to the cultural impact of imported animation, beginning with the relatively obscure anime feature Taro the Dragon Boy in 1979 (pictured), and followed swiftly by Astro Boy on television in 1982 (I presume that this was the 1980 colour remake, not Tezuka’s 1963 original), and a flood of both Japanese and American cartoons. Astro Boy, in particular, rode the spirit of the times, encapsulating the pro-science message of the Deng Xiaoping era, when Chinese science fiction experienced a brief boom in futurist speculation. Again, to split hairs from an industrial perspective, I would point out that from 1979 onwards, many of the “foreign” cartoons coming into China were also partly made there, although as before, this does not necessarily detract from the critical arguments that Wu is repeating.

Foreign rivals were in it to win it. Wu recounts the arrival of Hasbro in the early 1980s, which baffled the Chinese by handing the complete run of its Transformers cartoon series to broadcasters in Beijing and Shanghai. At first, it seemed insane, simply dumping a cartoon for free… until the toy stores started to fill up with robots. The pay-off from that era is highly visible today, not only in the blockbuster Chinese success of the Transformers movie franchise, but in Decepticon decals on half the boy-racer cars I see in Chinese cities. Back then, however, Chinese animators had to deal with a local quota system, whereby politically-sound, government-approved works from the Shanghai Animation Studio had a captive State-sponsored market at 8000 yuan a minute, whereas anyone lacking such patronage might have to sell their works for as little as 8 yuan – even in today’s money, that’s just a single UK pound.

The free market had the last laugh in 1989, when Shanghai’s animators defected en masse to commercial enterprises in the south. Wu’s book delineates several further key dates in Chinese animation – starting with 1990, the year that Dison Computer Graphics rolled out an animation system that now dominates the Chinese market (80%!) much as Celsys does in Japan. Then there’s 1995, the year that the market was supposedly “freed” – a hundred flowers didn’t bloom for long. Similar social engineering can be found in the government’s Five-Year Plans, which have recently treated the growth of animation like car-making or widget-manufacture, optimistically demanding an “output” of 30 animated features a year by 2015.

The free market had the last laugh in 1989, when Shanghai’s animators defected en masse to commercial enterprises in the south. Wu’s book delineates several further key dates in Chinese animation – starting with 1990, the year that Dison Computer Graphics rolled out an animation system that now dominates the Chinese market (80%!) much as Celsys does in Japan. Then there’s 1995, the year that the market was supposedly “freed” – a hundred flowers didn’t bloom for long. Similar social engineering can be found in the government’s Five-Year Plans, which have recently treated the growth of animation like car-making or widget-manufacture, optimistically demanding an “output” of 30 animated features a year by 2015.

Perhaps limited by a publisher determined to charge 50p a page (for which see below), Wu seemingly lacks the space to cover everything I would like to see. A fuller account of animation in China, I would suggest, should also include the aforementioned grunt-work below the line, not only for foreign companies, but for locals. Wu himself drops tantalising details of some of animation’s uses outside the aesthetically obvious features and TV market, such as Shanghai Animation’s digital water and ink effects in a 1995 commercial for Wuliangye booze, and the use of computer animation to recreate backdrops of the First Emperor’s palace in Zhou Xiaowen’s live-action The Emperor’s Shadow. There is, to be sure, an entire book’s worth of material about such elements, but they are outside Wu’s main focus – hopefully he will return to them another day. He also lacks the space for any treatment of the protectionism that haunts the Chinese market, such as the 21st-century putsch against Japanese cartoons that has contributed to much of the last decade’s local “successes”. It’s not much of a free market if the most popular competitors are excluded.

The concept of a “Chinese School”, which is not Wu’s own, but one he certainly embraces, has real resonances in the present day. You can hear much of it in the rhetoric of the directors of Big Fish and Begonia (pictured), as they proclaim the uniquely Chinese traits of their Ghibli pastiche. You can divine it, somewhere in the minutes of every studio meeting where a bunch of producers have gone with starry-eyed notions of originality and innovation, and come out announcing that they are going to back yet another remake of Monkey. Wu carries it through to his later chapters on independent animation and the rise of Flash, a software eminently suited to the cheap returns and small screens of Chinese viewership. Ever one to push a buzzword, he parses these as minjian – “made by the people”, which forms a neat symmetry with his earlier minzu – he calls for an “interdisciplinary cultural mechanism for studying animation”, but even his introduction throws in terms and assumptions that will only be intelligible to a Sinologist.

The concept of a “Chinese School”, which is not Wu’s own, but one he certainly embraces, has real resonances in the present day. You can hear much of it in the rhetoric of the directors of Big Fish and Begonia (pictured), as they proclaim the uniquely Chinese traits of their Ghibli pastiche. You can divine it, somewhere in the minutes of every studio meeting where a bunch of producers have gone with starry-eyed notions of originality and innovation, and come out announcing that they are going to back yet another remake of Monkey. Wu carries it through to his later chapters on independent animation and the rise of Flash, a software eminently suited to the cheap returns and small screens of Chinese viewership. Ever one to push a buzzword, he parses these as minjian – “made by the people”, which forms a neat symmetry with his earlier minzu – he calls for an “interdisciplinary cultural mechanism for studying animation”, but even his introduction throws in terms and assumptions that will only be intelligible to a Sinologist.

Wu’s book is a fine addition to the canon of books on China’s animation industry, in particular for its examination of the way that cartoons have been discussed at a governmental or political level, and for its impressively granular narrative of the last decade of independent animation, in everything from pop videos to student shorts. I wonder, though, if he is being justly served by his publishers, Routledge, who have priced his work so highly that it seems unlikely to be found anywhere outside a handful of specialist libraries. I have taken Routledge to task before for their pricing decisions, but here we go again. At 206 pages, this book is £115 in hardback and £109.50 on the Kindle. Is it a magic f***ing book? Do I get a free motorcycle with it? Is it going to be served in Jesus’s shoe? There’s a comments section right under this article, Routledge – feel free to defend yourselves with the numbers. Before you do, though, I would also like to point out that I just paid more than £100 for a book that twice fails to correctly spell the word “soldier”.

This is not a 1.1 million word encyclopaedia encapsulating an entire medium. It is not the only work of its kind in the English language on a forgotten medieval kingdom. It is not an analysis of a frightfully obscure war with a limited readership. I am no stranger to paying three-figure sums for books – I do it a dozen times a year, and many of those purchases are published by Routledge and worth every penny. But there comes a point where a cash-strapped librarian stacking shelves is sure to think: We can live without a Chinese animation section. All the books look like pamphlets and charge like Rolexes. There will undoubtedly be some who are obliged to rob Peter to pay Paul, forced to choose between Wu’s book or Sean MacDonald’s earlier Animation in China, thereby forcing Routledge authors to compete with each other. And despite the flaws of Rolf Giesen’s Chinese Animation from McFarland, there are many libraries for which I would have to concede that his more generalist book is a better bet than both of these. I’d prefer to have all three on the shelf, of course, but that would cost the same as a plane ticket to China.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History.

Leave a Reply