Books: Chinese Animation and Socialism

January 13, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Daisy Yan Du’s newly published collection Chinese Animation and Socialism: From Animators’ Perspectives focuses inevitably on the rise and fall of the Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS), which might reliably be described as the beating heart of the Chinese animation community for much of the mid- to late twentieth century. Refreshingly, the approach of much of the book relies on insider stories by the animators themselves, although not all of them are still with us. Tadahito Mochinaga, for example, the Japanese animator on Momotaro’s Sea Eagles who had an entire parallel career in China under the name Fang Ming, is remembered here in a chapter by his daughter Noriko.

Duan Xiaoxuan, the first animation camerawoman in China, reminisces about the early days of the Shanghai studio, and the role of other female workers in creating its works. One such staffer, the animation director Lin Wenxiao, also talks through her career, up to and including her solo directorial debut, The Snow Boy.

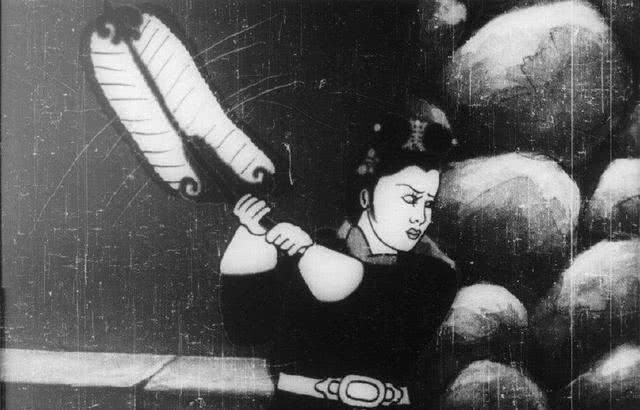

Kosei Ono writes a chapter specifically about the impact of Chinese cartoons in Japan, beginning with the watershed success of Princess Iron Fan, conceived in China as an anti-Japanese parable, but screened in wartime Japan as an innocent children’s cartoon retelling an episode from Journey to the West. Of course, it also spooked the hell out of the Japanese Navy, which threw money into making a rival feature so that Japan could regain the cultural high ground – the result was Momotaro: Sacred Sailors.

The most intriguing part of Ono’s account is his reminiscence about the brief flurry of interest in Chinese animation in Japan in the early 1980s, when the works of SAFS descended en masse as part of a Sino-Japanese cultural exchange, and led to several high-profile touring exhibits. But what’s interesting about it is Ono’s mourning of the passing of the sort of “shopping malls willing to sponsor cultural events.” He writes that “the character of shopping malls has changed and the venues have gone.” Although he does not mention it directly, he is alluding to the largesse of Japan’s Bubble economy, where a brief boomtime windfall left malls trying to outbid each other to stage cultural events as bait to drag in more shoppers.

A particularly original chapter for me comes in the form of Ding Jianhua’s memoir of life as a voice-actress. She recalls not only her labours dubbing Chinese cartoons and foreign films, but an entire shadow-line of distribution known as the “internal reference films.” These were contraband foreign movies, brought in for screening to the Party elite in the 1970s, but kept away from the general population. The mind boggles at the thought of Chairman Mao sitting down to a private screening of a Chinese-language dub of The Railway Children, supposedly to check it for capitalist propaganda, but possibly also just letching after Jenny Agutter.

Yan Dingxian, who designed the iconic Monkey King for Uproar in Heaven, here looks back on a career that took him from the ranks of the animators to the head of the studio in the hectic 1980s. His successor, Chang Guangxi, takes the story into the 1990s, past the moment in 1995 when SAFS lost the “iron rice bowl” of its protected status, and was forced to compete on the open market – the result being Lotus Lantern, an uneasy mix of National Style and blatant Disneyism.

Zhou Keqin writes winningly of his time as the boss of Yilimei, the studio spun off from SAFS to work specifically on outsourced foreign animation. I have often heard Chinese animation historians speak of the “Great Escape” of 1986, as animators ditched Shanghai en masse to work for more lucrative foreign clients. But nothing really puts it in perspective as well as Zhou’s account, in which he turns up at Yilimei to discover “a scene of desolation.” In the wake of a film festival to show off Shanghai’s talent, literally dozens of the self-same talent had jumped ship to work for contacts they had met at the festival, including twenty-seven members of Zhou’s forty-strong staff.

Zhou writes proudly of working on an anime feature that he calls “I Want to be the Fifth”, which can be found in the Anime Encyclopedia as Run, which I presume to have been the title used to flog it in sales sheets. Based on a novel by Etsuko Kishikawa, it was a film about a disabled girl who dreams of coming in next-to-last just once in the school sports meet. In other words, “I Want to Come in Fifth” might have been a better translation of the original title, but as noted elsewhere by Chang Guangxi, Chinese animators tended not to pay much attention to the words in the scripts they worked on, since the bulk of their labour relied solely on the visual cues from storyboards.

There are many parallels between the rise of the SAFS and the similar issues faced by its contemporary a world away, Toei Animation in Japan. In such a vein, Yan Shanchun, director of Storm in a Desert, discusses his origins as a complete novice, and how the SAFS training scheme made an animator out of him. Although the late Dai Tielang was too ill to come to the conference in 2017 that informed many of these papers, Du goes the extra mile to interview him at his home, adding a valuable chapter on the five-episode Police Chief Black Cat, one of the early triumphs of Chinese television cartoons, a surprisingly violent sci-fi story about a feline enforcer on a motorbike.

Because “animation under socialism” effectively means anything that the Shanghai Animation Film Studio did during its lifespan, there is a lot about the studio’s role in creating what is translated here as the “National Style” (sometimes also referred to as the Chinese School). This is a huge issue in Chinese animation history, amounting to an argument towards and about the necessity to make Chinese animation that looks Chinese – a sense, increasingly shrill in these days of “cultural security” clampdowns, that it is the patriotic duty of Chinese animators to create material that affirms Chinese culture, preserving its values and traditions rather than churning out Disneyalikes. These are noble sentiments, even if in modern times they seem to perpetually be used to drag everything kicking and screaming down to the level of Yet Another Monkey King remake.

Several of the contributors write interesting chapters on what this all means at the production level, particularly the scriptwriter Ling Shu, who is witty and informative about the problems of meeting political targets when the politics itself keeps changing. Having once been defeated by contradictory censorship directives myself – Is a myth tradition, and hence welcome? Or is it superstition, and hence not allowed? – I greatly enjoyed his stories of the scandals behind the scenes, including the panel of festival judges who furiously took his Monkeys Fish for the Moon out of competition when the director refused to explain what it was about. Meanwhile, as the Cantonese accent in his name suggests, Fung Yuk Song was an animator in Shanghai, but emigrated to Hong Kong, where he remembers his work on propaganda cartoons, which similarly had to be just Chinese enough for some censors, and not too Chinese, or the wrong sort of Chinese, for others.

Pu Jiaxing discusses his own role in the creation of the National Style, and Pu Yong writes about paper-cut animation, a style deliberately used to evoke domestic traditions. Similarly, composer Jin Fuzai discusses the way he tried to embody character and motion of the animation in his music. Du herself, in her conclusion, recounts the tale of Nelson Chu, the bright young doctoral candidate at a Hong Kong technical college, who developed software that could simulate and animate the properties of ink painting. Chu’s software proved ideal for applying a “National Style” to the animated credits for the Beijing Olympics. Subsequently, he was lured back from the United States by Lo Wing Keung, a fellow graduate of the college, in order to work on the cartoon Red Squirrel Mai.

The point is not lost on me here that the liberal arts environment of Hong Kong before the 2010s proved to be a lucrative and enduring crucible for artistic and technological achievement, supplying much of the talent that the People’s Republic subsequently brags about. In the case of Lo, he grew up in Hong Kong and only went to China proper in 2004 in order to make Pleasant Goat and the Big, Big Wolf, which then became the poster-child for the rise of “Chinese” animation. For the PRC to call him a local boy is not geopolitically untrue, but somewhat facetious.

As Du herself notes in her conclusion, such transnational connections behove anyone in the field to “pay particular attention to the role of Hong Kong in histories of Chinese animation,” since Hong Kong seems to have supplied a huge part of the talent, investment and know-how that has helped revitalise Chinese (and Japanese) animation in recent decades.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Chinese Animation and Socialism, edited by Daisy Yan Du, is published by Brill.

Leave a Reply