Books: Floating Worlds

February 2, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Staking a claim for Japanese animation as one of the world’s “richest and most interesting artistic forms”, Maria Roberta Novielli’s Floating Worlds: A Short History of Japanese Animation briskly chronicles the last hundred years of the medium, from its first, scrappy screenings in 1917, through its uses in wartime propaganda, post-war artistic experiments, the diversification of arthouse shorts, worthy adaptations of children’s literature, and the recent successes of Studio Ghibli and Makoto Shinkai. In doing so, she deliberately chooses a quirky perspective that ignores a lot of the more familiar terrain in anime history. “Not all the titles known to the general public were taken into account,” she writes, “…many names described in the next pages are not as popular in the West, meaning that the book also tries to suggest new visions together with the mainstream ones.”

Staking a claim for Japanese animation as one of the world’s “richest and most interesting artistic forms”, Maria Roberta Novielli’s Floating Worlds: A Short History of Japanese Animation briskly chronicles the last hundred years of the medium, from its first, scrappy screenings in 1917, through its uses in wartime propaganda, post-war artistic experiments, the diversification of arthouse shorts, worthy adaptations of children’s literature, and the recent successes of Studio Ghibli and Makoto Shinkai. In doing so, she deliberately chooses a quirky perspective that ignores a lot of the more familiar terrain in anime history. “Not all the titles known to the general public were taken into account,” she writes, “…many names described in the next pages are not as popular in the West, meaning that the book also tries to suggest new visions together with the mainstream ones.”

There are a million ways to approach any history, and there is ample room for a narrative that examines animation in Japan through, say, the work of its most lauded independent creators or its relationship to the society that birthed it. There’s more to it than porn and Pokémon, and indeed, many of the biggest franchises of modern anime are reduced to walk-on roles as Novielli focuses instead on festival screenings and independent shorts.

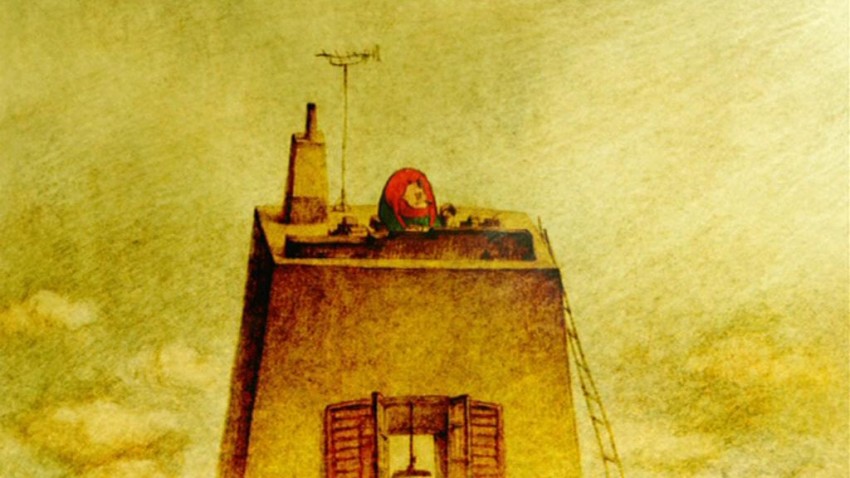

Novielli’s approach often concentrates on experimental films, undeniably an important and often-overlooked element of the medium. She presents an overview of the movers and shakers of Japanese independent animation, who have a symbiotic and codependent relationship with the commercial sector. Kunio Kato comes to mind – a man who has to book an appointment to visit his own Oscar for La Maison en Petits Cubes (pictured) because he made it on company time at Robot and it is hence forfeit to his employers. However, Novielli does not really engage with this dilemma, instead describing him as an independent animator who “joined the Robot Studio animation team, where he produced all his films.” Indeed he did, alongside all the animated logos, commercials and inserts that actually paid the bills.

Novielli’s approach often concentrates on experimental films, undeniably an important and often-overlooked element of the medium. She presents an overview of the movers and shakers of Japanese independent animation, who have a symbiotic and codependent relationship with the commercial sector. Kunio Kato comes to mind – a man who has to book an appointment to visit his own Oscar for La Maison en Petits Cubes (pictured) because he made it on company time at Robot and it is hence forfeit to his employers. However, Novielli does not really engage with this dilemma, instead describing him as an independent animator who “joined the Robot Studio animation team, where he produced all his films.” Indeed he did, alongside all the animated logos, commercials and inserts that actually paid the bills.

This attitude is illustrative of a general tone in the book that often privileges aesthetically pleasing, award-winning festival moments ahead of animation and animators that are more widely seen and sold. This is a worthwhile corrective to other writers’ concentration on blockbuster box-office or supposed fan favourites, although sometimes Novielli forcefully reads an “independent” status into anything she wants to include, while discounting the achievements of commercial animators in the same field. She writes, for example, that the arthouse director Koji Yamamura also teaches at an animation college, which is true… but so does Ryosuke Takahashi (VOTOMS), and so does Ichiro Itano (Gantz). Novielli describes Sadao Tsukioka as a man who “became an independent animator in 1964 when he directed Cigarettes and Ashes… for Tezuka Osamu’s Mushi Production,” without acknowledging what a contradiction in terms this is. There is a cyclical relationship between art and commerce in Japanese animation; as Novielli recognises when she writes about the Group of Three in the 1960s, sometimes arthouse animation is an audition for commercial work, or commercial work is a patron that funds the arthouse.

Novielli’s earlier Italian book, Animerama: Storia dell’animazione giapponese (published in 2015, although her own references misdate it to 2001), was a hundred pages longer than this one, so I suspect that many of each chapter’s copious endnotes are attempts to smuggle details back in that she was forced to cut from the text of a truncated English edition. Most of them contain incidental information, such as plots of films or biographies of creators, which might as well have been in the book proper, but very few actual citations allow the reader to investigate her claims. Novielli has plenty of interesting factoids to hand, but when she writes, for example, that My Neighbour Totoro was distantly inspired by Kenji Miyazawa’s Wildcat and the Acorns, she provides no reference. She dates “Japan’s first cosplay parade” to 1978, which will be news to some, but omits any citation that can be tested. You just have to take her word for it.

Bafflingly, Novielli also appears to have written and delivered an entire book on the history of Japanese animation without once having encountered a copy of Anime: A History by Jonathan Clements, a remarkable oversight when she is able to pour the entire series of Mechademia into her bibliography. It’s difficult to believe that she has never heard of this 2013 book, which could have been an immense help to her in formulating a structure of enquiry and avoiding certain errors in historical practice. I certainly hope her publishers knew about it, or else their willingness to publish a work in English that is half the size and twice the price would look foolhardy. I can only presume that her refusal to even mention it is some sort of epistemic exercise, as she deliberately constructs a vision of Japanese animation history that is hers alone.

Novielli’s other touchstone seems to be the appreciation accorded to films when they win awards. When she gets to Hakujaden, anime’s first colour feature in 1958, she observes that the film won a prize at the Venice Film Festival, albeit without really asking why. It left me wishing for a more involved consideration of what that might mean, since this is the same Hakujaden that also picked up a bunch of awards in Japan, most of them consolation prizes or half-hearted pats on the back for effort. Its own animators were so disenchanted with it that Yasuji Mori threatened to shave off all his hair if it made it into that year’s Kinema Junpo Top Ten.

Novielli’s other touchstone seems to be the appreciation accorded to films when they win awards. When she gets to Hakujaden, anime’s first colour feature in 1958, she observes that the film won a prize at the Venice Film Festival, albeit without really asking why. It left me wishing for a more involved consideration of what that might mean, since this is the same Hakujaden that also picked up a bunch of awards in Japan, most of them consolation prizes or half-hearted pats on the back for effort. Its own animators were so disenchanted with it that Yasuji Mori threatened to shave off all his hair if it made it into that year’s Kinema Junpo Top Ten.

I’m actually quite fascinated by the prospect of a book that views Japanese animation solely through the lens of festival screenings and accolades, but Novielli could have been a little clearer, with herself and with her readers, about this approach. She seems to think that any prize is a mark of objective quality, whereas I know of a European festival that handed one out to a well-known Japanese director just to stop him smashing up the furniture.

Novielli comes tantalisingly close to having written an occasionalist history of “Japanese animation that wins prizes and gets shown in festivals.” If she or her editor had only realised this, such a methodology could have structured a remarkably wide-ranging and incisive approach, both in terms of outside recognition and the medium’s own sense of self-worth. It would have prompted some interesting thoughts about the politics of how awards come into being – who gets a gong, when they get it and why. As noted in Anime: A History, at least part of the discourse surrounding the very term “anime” arose in the 1970s as the festival crowd used it as a word to distinguish the junk on television from their own self-consciously worthy pieces. And yet, with the arrival of a dedicated anime press in the 1980s, the anime medium started handing awards to itself, generating a whole new political economy and canon. Such self-congratulations persisted for years, until an otaku take-over at Japanese conventions started putting anime and manga in the frame for SF awards… and then, by the 1990s, we get the likes of Hayao Miyazaki finally being recognised outside the field and outside Japan. Novielli finishes, of course, with the world-beating successes of Miyazaki and Shinkai, but does not seem to have noticed that the politics of prize-winning is the unstated theme that links so many parts of her book.

Floating Worlds: A Short History of Japanese Animation is published by CRC Press.

Leave a Reply