Books: History of Modern Manga

May 23, 2023 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

“The history of manga,” notes the back-cover blurb for Matthieu Pinon and Laurent Lefebvre’s new book, “is inextricably tied to Japan’s social, economic, political, and cultural evolution.” But the authors neglect to mention the real selling point, which is that their History of Modern Manga actually bothers to point out where those ties might be.

The authors skirt around much of the throat-clearing and nit-picking of manga pedantry, by refusing to get bogged down in its early days. A concise introduction summarises the developments in Japanese graphic arts before the middle of the 20th century, and the book proper starts in 1952, the year that the Allied Occupation was officially over, and Japanese media could expect a return to some degree of freedom.

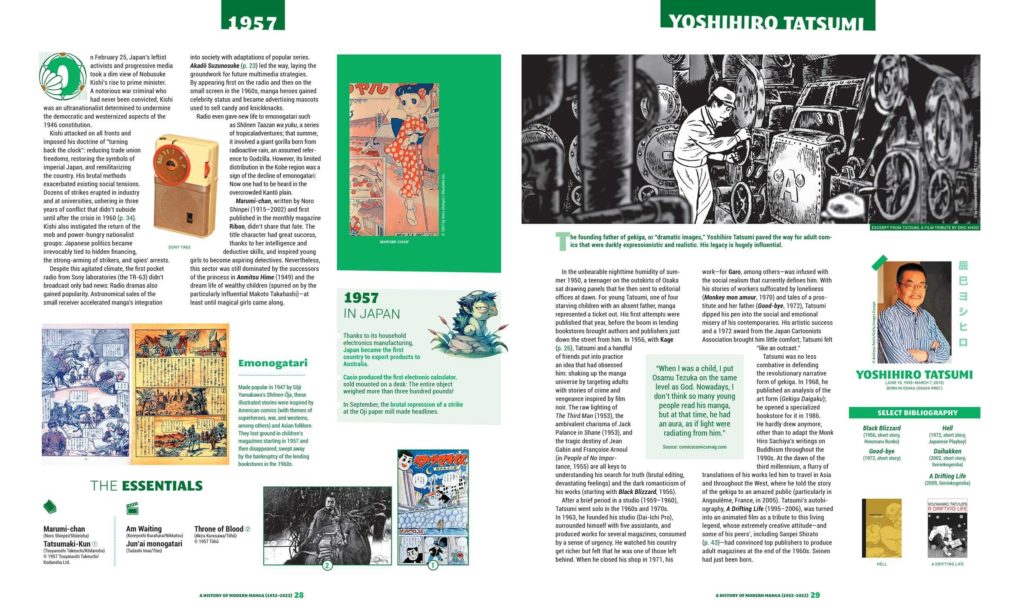

Many of the left-hand pages are devoted less to manga than to the march of history in Japan, and come riddled with valuable contextual notes – the sort of things that get ditched for space in many other books, but provide crucial pillars of understanding. These include such gems as the price of a television set in 1952; the fact that Osamu Tezuka’s first run at Princess Knight was several years before the version that is remembered today; the sudden rise of the Audrey Hepburn hair-style; the release of the first Casio calculator; the criminalisation of prostitution (insightfully described here as a boon for the Yakuza); the first appearance of the Washlet toilet, and a thousand other things that make manga make sense.

Pinon and Lefebvre navigate a frankly impossible series of concerns, cramming in historical context, important figures, representative works and intriguing gossip. With an industry the size of Japan’s there is sure to be whataboutery, but in concentrating on 71 major creators, the authors hit all the high points. But it’s their contextual verso pages that are the real joy. Far too many writers on manga blunder into it as if it is the only thing that is going on, either because they are comics specialists foraging outside their comfort zone, or because they are Japan specialists who don’t realise what a lay reader might need to know. But Pinon and Lefebvre’s historical commentary is exciting and informative, firmly grounding Japanese comics in what was going on in the world around them. It will come as an absolute God-send to the teacher who wants to engage their students with Japan, through the medium that the students are already reading for fun.

It also allows them a sneaky hack denied by other formats, which is the chance to return to authors and titles already mentioned, in order to highlight the growing media footprints of their work. So, Katsuhiro Otomo gets his own page in 1980, but when Akira suddenly sets the world on fire in 1982, he can crop up again on the left-hand side of someone else’s story, sparking with apocalyptic fervour on the side-lines while the authors are talking about the altogether bubblier Yumiko Igarashi.

The authors have plainly leaned on dozens, if not hundreds of articles and books, but only credit seven “recommended” titles in their bibliography, along with Rachel Thorn’s website. This makes the book less useful for older readers, while occasional small-print acknowledgements of sources in-text make it seem like each spread only relies on a single website or article, which I am sure is a disservice to the authors.

No translator is credited, although the indicia has room for four vice presidents, four editors and two editorial assistants. For whatever reason, this has led to one or two moments of translatorese, as the uncredited wordsmiths (perhaps the authors themselves?) struggle to Anglicise some rather French turns of phrase. On occasion, there are also some thesaurus-busting moments when I wonder if a young reader will really be able to follow the text. “A speech bubble containing an ellipsis is enough for any Japanese person to recognise Golgo 13,” enthuses the Takao Saito entry. Yes, but is that enough for a teenager to know what an ellipsis is?

The authors adopt a noble policy of using English-language titles where a work has been published in translation, but leave untranslated Japanese titles in untranslated Japanese, usually without bothering to explain what they mean. So, while it’s nice to know that Hiroshi Hirata wrote a comic called Mumei no Hitobito Ishoku Retsuden, the reader who cannot speak Japanese is entirely in the dark as to what that might actually mean. However, this is usually a victimless crime – I much prefer to have too much information on the page, on the off-chance it might prove useful to someone, as opposed to nothing but hand-wavingly vague comments and a bit of art.

A dozen spreads at the back mop up anything the authors might have missed in their previous methodology, with some welcome commentary on gourmet manga, robots, apocalypses and so on. “If you are a newbie to manga,” the authors write, “you can certainly find the perfect series to dive into.” And that’s certainly true – this is an excellent introduction to manga, especially for the curious teen.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. A History of Modern Manga (1952-2022) is published in English by Insight Editions.

Leave a Reply