Books: Ishiro Honda

July 28, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

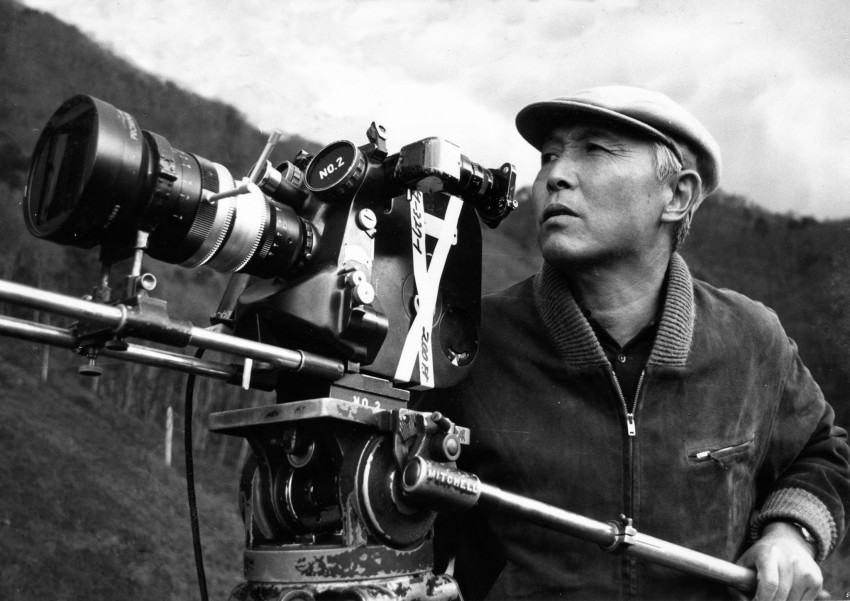

Ishiro Honda is an easy filmmaker to ridicule. Here is a man whose name, more by accident than design, looks set to be forever identified with a certain giant fire-breathing lizard, and by extension Japan’s entire home-grown strain of giant monster movies that followed in its wake, featuring men in rubber suits laying waste to scale-model replicas of the country’s urban centres.

Ishiro Honda is an easy filmmaker to ridicule. Here is a man whose name, more by accident than design, looks set to be forever identified with a certain giant fire-breathing lizard, and by extension Japan’s entire home-grown strain of giant monster movies that followed in its wake, featuring men in rubber suits laying waste to scale-model replicas of the country’s urban centres.

Indeed, rather than “the director of Godzilla”, it might be more apt to refer to him as “Godzilla’s director.” Japan’s most celebrated cinematic offspring pretty much owned him for the latter half of his career. Perhaps it is inevitable that Honda has avoided the kind of meticulous in-depth scrutiny afforded to contemporaries such as Ozu, Naruse and Kurosawa, even though his films have reached far wider global audiences.

The Godzilla franchise itself has courted much attention in publications including Jim Harmon’s The Godzilla Book (1986), Frank Lovece’s Godzilla: The Complete Guide to Moviedom’s Mightiest Monster (1998), William Tsutsui’s Godzilla on My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters (2004), David Kalat’s A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series (2007) and a whole raft of magazine articles, academic papers and anthology chapters. Meanwhile, August Ragone’s beautifully illustrated tome Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters: Defending the Earth with Ultraman and Godzilla (2007) shone the spotlight on the special effects guru who first gave the creature its form.

However, when it comes to any analysis of the wider filmography of the original film’s director, Peter H. Brothers’ Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda (2009) has thus far been the main go-to source. This book still only concerns itself with Honda’s fantasy films, effectively ignoring the other half of his output.

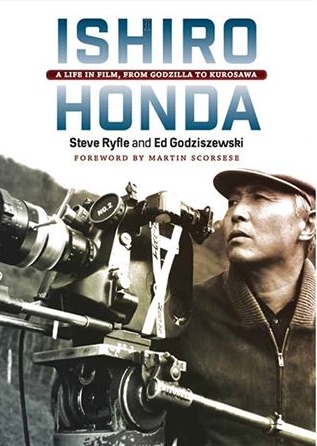

Not so Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa, an exhaustive attempt to reappraise the director’s legacy. Its 336 fact-packed pages rigorously detail all aspects of Honda’s life and work, from growing up as the son of a Buddhist monk in mountainous Yamagata prefecture, through the repeated wartime call-ups that wrenched him from his early filmmaking career at PCL studios, to his final years on the later films of Akira Kurosawa, the long-term friend with whom he once shared an apartment in the 1930s.

Not so Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa, an exhaustive attempt to reappraise the director’s legacy. Its 336 fact-packed pages rigorously detail all aspects of Honda’s life and work, from growing up as the son of a Buddhist monk in mountainous Yamagata prefecture, through the repeated wartime call-ups that wrenched him from his early filmmaking career at PCL studios, to his final years on the later films of Akira Kurosawa, the long-term friend with whom he once shared an apartment in the 1930s.

One of the main obstacles facing any serious appraisal of Honda’s technique has been the question of how much he brought to the table as the director of type of film that relied so much on what other people put on the screen. The original 1954 Godzilla was scripted by Takeo Murata (although Honda gets a co-writer credit), based on an “original story” that Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka commissioned from Shigeru Kayama, whom the authors describe as “a popular writer of detective mysteries and speculative adventures in the vein of English author H. Rider Haggard.” This “original story”, as many have pointed out and Ryfle and Godziszewski themselves attest, was in reality anything but; it was effectively a reworking of Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (released in America in June 1953, although it actually only surfaced in Japan a month after the premier, on 3rd November 1954, of Godzilla), also taking ideas from King Kong, which had just been reissued in Japan in 1952, and also the 1925 silent version of The Lost World.

As the authors emphasise, “Godzilla wasn’t Honda’s idea, and he wasn’t Toho’s first choice to direct it.” There is also the thorny issue of Eiji Tsuburaya’s input. The special effects maestro was a domineering figure at the studio, hailed as “the god of special effects” following his startling re-creation of the bombing of Pearl Harbour in the infamous propaganda film The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942). Honda had worked with Tsuburaya on his war movie Eagle of the Pacific (1953), made just prior to Godzilla, and the pair would collaborate on many of the director’s subsequent works right up to King Kong Escapes (1967). Again, the word “collaborate” is slightly problematic, as Tsuburaya was fiercely protective of his role in putting his special effects sequences onscreen, leaving Honda working mainly on just the scenes of human drama. It is fair to say that their working relationship, as detailed by the authors, was not always an equal or a smooth one.

The bitterest irony is that Honda’s own input was almost completely effaced from the international version of the original film that circulated outside of Japan under the title of Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, dubbed and re-edited with additional footage shot in America featuring Raymond Burr as a reporter covering the attack. A similar fate befell all of Honda’s subsequent science-fiction and monster movies, so that while the works that bore his name on the credits as director had a global reach through both cinema releases and, more crucially, television syndication, they often bore scant resemblance to the original films that he had actually directed. It was only when Godzilla was reissued overseas in its original cut some fifty years later that Honda’s contribution could be fully appreciated.

The bitterest irony is that Honda’s own input was almost completely effaced from the international version of the original film that circulated outside of Japan under the title of Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, dubbed and re-edited with additional footage shot in America featuring Raymond Burr as a reporter covering the attack. A similar fate befell all of Honda’s subsequent science-fiction and monster movies, so that while the works that bore his name on the credits as director had a global reach through both cinema releases and, more crucially, television syndication, they often bore scant resemblance to the original films that he had actually directed. It was only when Godzilla was reissued overseas in its original cut some fifty years later that Honda’s contribution could be fully appreciated.

Godzilla provided Toho with a significant commercial hit, despite mixed reviews at the time of its release. This was, it should be remembered, Japan’s first major science fiction film. It was the eighth highest grossing Japanese title of 1954, although it seems the studio heads did not initially regard Honda as an integral part of this success, as while Tsuburaya remained onboard for the sequel, Godzilla Raids Again (1955), released in the States as Gigantis, the Fire Monster, it was another director, Motoyoshi Oda, who was assigned to direct.

Not that this appears to have unduly concerned him. Like the eight titles he directed before this seminal kaiju, which include his early documentaries Ise-shima (1949) and Story of a Co-op (1950), the whaling drama The Man who Came to Port (1952), the high-school youth movie Adolescence Part 2 (1953), and the two war (or rather anti-war) films Eagle of the Pacific (1953) and Farewell Rabaul (1954), his subsequent films occupied a number of genres. His immediate follow-up to Godzilla was the romance Love Makeup (1955) and later films, which include the melodrama Mother and Son (1955), three musical vehicles for new pop sensation Chiyoko Shimakura beginning with People of Tokyo, Goodbye (1956), a salaryman drama starring Takashi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune entitled Good Luck to these Two (1957), and the baseball movie Inao: Story of the Iron Arm (1959), way outbalance his more fantastical output. At one point, Kurosawa even had Honda earmarked to direct his script of Throne of Blood.

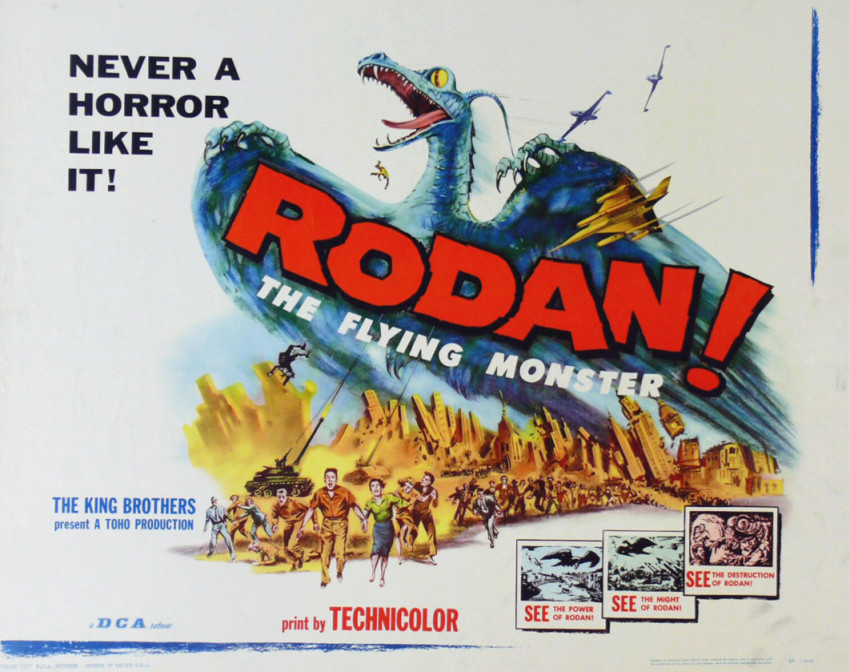

It is true, there were also genre titles like the abominable snowman horror Half Human (1955), his first colour film Rodan (1956) featuring the eponymous radioactive pteranodon, the alien-invasion film The Mysterians (1957), the gangster-noir-horror hybrid of H-Man (1958), and the legendary monster moth movie Mothra (1961). Nevertheless, it was not until Toho decided to commemorate its 30th anniversary with King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) that Honda was reunited with the character whose birth into the pantheon of global movie monsters he was so instrumental to. The highest-attended Godzilla movie ever in Japan, its success saw Honda near exclusively pigeonholed within monster movies and sci-fi for the rest of his career. There were a few memorable moments along the way – and I will tip my hat towards the mycological mutants of Matango (1963) – but the film effectively marked the beginning of the end for the director.

It is true, there were also genre titles like the abominable snowman horror Half Human (1955), his first colour film Rodan (1956) featuring the eponymous radioactive pteranodon, the alien-invasion film The Mysterians (1957), the gangster-noir-horror hybrid of H-Man (1958), and the legendary monster moth movie Mothra (1961). Nevertheless, it was not until Toho decided to commemorate its 30th anniversary with King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) that Honda was reunited with the character whose birth into the pantheon of global movie monsters he was so instrumental to. The highest-attended Godzilla movie ever in Japan, its success saw Honda near exclusively pigeonholed within monster movies and sci-fi for the rest of his career. There were a few memorable moments along the way – and I will tip my hat towards the mycological mutants of Matango (1963) – but the film effectively marked the beginning of the end for the director.

Honda was ultimately seen as someone who would get whatever job was handed to him done without fuss. Nevertheless, while his sci-fi and monster spectacles guaranteed at least some form of steady revenue stream for Toho from overseas sales, there were diminishing returns at the local box office. Production budgets nose-dived across the 1960s as television continued its slow and relentless attrition of cinema audiences. Destroy All Monsters (1968) became Toho’s last monster movie to get a proper theatrical release until the series was resurrected in the 1980s. The titles from All Monsters Attack (1969) through to Honda’s directorial swansong with Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975) were instead relegated to playing as part of the perennial “Toho Champion Festival” kids’ holiday programmes, alongside a mixture of shorts, TV episodes, cartoons and cut-down reissues of older monster classics.

It might all have been different. Kurosawa once advised Honda to cut loose from Toho and form his own independent production company to make movies that the studio would then distribute, as he himself had done in 1959. Tsuburaya, too, had set up his own company in 1963 and discovered the burgeoning television market to be a lucrative cash cow from 1966 onwards though special effects series such as Ultra Q and Ultraman. Ironically, Honda’s son Ryuji ended up embarking on a long career in TV production when he answered a call to join Tsuburaya Productions. Honda senior. however, fully aware he had spent far too long making the kinds of film he wasn’t really interested in yet never one to rock the boat, opted for loyalty to the company where he’d spent his entire filmmaking career, a loyalty that sadly was not reciprocated as, after almost 40 years at the studio, he fell prey to corporate restructuring and was put out to pasture.

Honda’s mellow, easy-going temperament is undoubtedly key to understanding this trajectory. His producer Tanaka admits: “I am responsible for tying Honda to special effects movies. If I hadn’t, he might have become a director just like Naruse.” His apparently passive approach to his career can also be understood in terms of his war experiences, which Ryfle and Godziszewski detail as much as they are able, but about which Honda himself remained understandably reticent, even to his nearest and dearest. A convenient family connection had exempted Honda’s contemporary Kurosawa from military conscription. Honda was not so lucky. He ended up drafted on three separate occasions, losing almost a decade to active overseas service, mostly in China. By the time the war was over, Kurosawa was well into his directing career, while the shell-shocked Honda effectively had to start from scratch, returning to his metier as an assistant on his sympathetic friend’s Stray Dog (pictured, 1949). As the authors point out, whereas Kurosawa’s dramas are marked by heroism and conflict, Honda’s usually tend to call for world harmony and empathy with the other, no matter how monstrous.

Honda’s mellow, easy-going temperament is undoubtedly key to understanding this trajectory. His producer Tanaka admits: “I am responsible for tying Honda to special effects movies. If I hadn’t, he might have become a director just like Naruse.” His apparently passive approach to his career can also be understood in terms of his war experiences, which Ryfle and Godziszewski detail as much as they are able, but about which Honda himself remained understandably reticent, even to his nearest and dearest. A convenient family connection had exempted Honda’s contemporary Kurosawa from military conscription. Honda was not so lucky. He ended up drafted on three separate occasions, losing almost a decade to active overseas service, mostly in China. By the time the war was over, Kurosawa was well into his directing career, while the shell-shocked Honda effectively had to start from scratch, returning to his metier as an assistant on his sympathetic friend’s Stray Dog (pictured, 1949). As the authors point out, whereas Kurosawa’s dramas are marked by heroism and conflict, Honda’s usually tend to call for world harmony and empathy with the other, no matter how monstrous.

All of these aspects combined make it easy to overlook Honda’s considerable achievements as a director. His non-fantasy work, never distributed in the West, remains little seen and even less discussed, even in his home country. Nevertheless, he had already laid the groundwork for the impressive underwater scenes in Godzilla in his debut, Ise-shima (1949), a factual film about a community of women divers, and his dramatic debut set in the same milieu, The Blue Pearl (1951), which employed a documentary realism combined with hint of romanticism that Honda acknowledged was inspired by Robert Flaherty. These were the very first films in Japanese film history to use underwater photography. The latter title also broke new technical ground in the audio field, with the substantial parts of the dialogue recorded on location to reduce the need for studio post-dubbing.

There was also his integration of rear-projected footage of ships at sea in the The Man who Came to Port (1952), and the dynamic aerial skirmishes contained within the Philippine-set Farewell Rabaul (1954), whose dramatic portrait of an isolated outpost of Japanese airmen encircled by US marines owed much to Honda’s own wartime experiences. Worth also noting here is the presence of the actress Akemi Negishi playing an exotic local dancer, mere months after her sensational debut in Josef von Sternberg’s Saga of Anatahan (1953). As well as appearing in a number of Kurosawa films, Negishi plied her stock-in-trade playing earthy and sensuous native types in several other Honda films; as a primitive mountain girl in Half Human (which includes another technical innovation in the form of a brief stop-motion animated effects sequence) and as one of the South Seas tribal dancers in King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962).

Between 1949 and 1975, Honda made some fifty films, but there has been little to no scholarship on the titles he made outside of the science-fiction or monster movie fields. In reality, there has been precious little on Toho’s work outside of these fields either, save for the auteurist studies of the more prominent names that the company produced.

Ryfle and Godziszewski’s largely biographical approach to their subject is a most welcome one then, in that it not only serves to reframe Honda’s own place in the scheme of things, but provides a whole host of fresh information about the production environment, the star system and other commercial contexts in which all of the studio’s employees operated. In an era when so much writing about Japanese cinema seems to be about offering new readings of the same old canon, it is nice to see a book that attempts to expand that canon, to tell us something new and to direct our attention to the many paths yet to be explored.

Jasper Sharp is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

Leave a Reply