Books: Lone Wolf & Cub

December 6, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

The Lone Wolf and Cub (also known as the Baby Cart) series, comprised six feature-length films released between 15th January 1972 and 24th April 1974, which are the subject of the ninth and most recent publication from UK film distributor Arrow’s recently established Arrow Books line.

The Lone Wolf and Cub (also known as the Baby Cart) series, comprised six feature-length films released between 15th January 1972 and 24th April 1974, which are the subject of the ninth and most recent publication from UK film distributor Arrow’s recently established Arrow Books line.

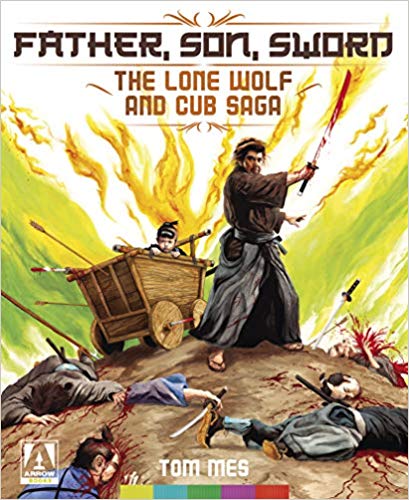

Father, Son, Sword is Arrow’s third title devoted to Japanese material, following on from Andrew Osmond’s monograph on Ghost in the Shell, published little over a year ago, and – if one doesn’t count Cult Cinema: An Arrow Video Companion (2016), an anthology comprised largely of liner note essays reproduced from their home video releases – the book that launched the imprint series proper, Unchained Melody: The Films of Meiko Kaji by Tom Mes.

Mes’ second contribution to Arrow’s line of pocket-sized guides seems a natural fit for both author and publisher. Although incredibly well-made, the Lone Wolf films represent the kind of popular exploitation cinema that has tended to escape attention from mainstream critics. However, they are undeniably seminal titles in the fan scene emerging around Japanese cinema prior to the DVD boom, and most certainly warrant putting into context.

Adapted from the Kozure Okami manga series, written by Kazuo Koike and illustrated by Goseki Kojima between 1970 and 1976, the films were produced by Zatoichi star Shintaro Katsu’s independent production company Katsu Pro and starred Katsu’s older brother Tomisaburo Wakayama as the near superheroic figure of Itto Ogami, the renegade former executioner to the shogunate. The master swordsman’s flees from the treacherous Lord Retsudo of the shadowy Yagyu Clan responsible for the murder of his wife, trundling his infant son Daigoro across the hinterlands of Edo-era Japan in a makeshift pram containing a deadly arsenal of lethal weaponry, while earning his keep as an assassin for hire.

Adapted from the Kozure Okami manga series, written by Kazuo Koike and illustrated by Goseki Kojima between 1970 and 1976, the films were produced by Zatoichi star Shintaro Katsu’s independent production company Katsu Pro and starred Katsu’s older brother Tomisaburo Wakayama as the near superheroic figure of Itto Ogami, the renegade former executioner to the shogunate. The master swordsman’s flees from the treacherous Lord Retsudo of the shadowy Yagyu Clan responsible for the murder of his wife, trundling his infant son Daigoro across the hinterlands of Edo-era Japan in a makeshift pram containing a deadly arsenal of lethal weaponry, while earning his keep as an assassin for hire.

The opening entry, Sword of Vengeance (1972), was first screened in the West as part of a “Japanese film series” of four Toho movies held at New York’s Elgin Theatre in 1973, where it was panned by New York Times critic Howard Thompson as “a blunt melodrama… Sword of Vengeance may be a swinger, but it’s all been swung before – over in Japan and here, too.” It is worth noting the newspaper’s critics also complained about the “white-on-white” English subtitles and were equally dismissive of the other films in the series, which included another future cult classic Lake of Dracula.

While failing to catch fire theatrically, Sword of Vengeance eventually made it to video in North America, along with a number of its sequels, several decades later courtesy of AnimEigo. An early pioneer in Western anime distribution established in 1988, the company was also responsible for introducing Meiko Kaji to the West as Itto’s Meiji-era female counterpart in the two Lady Snowblood titles. Indeed, for many growing up in the VHS era, such titles were memorable eye-openers, providing a striking but tantalising insight into what the mysterious but beguiling parallel world of Japanese cinema had to offer. The Lone Wolf films were later released on DVD in the UK by Artsmagic, while last year’s Criterion Blu-ray boxset stands as a testament to just how central the series has become within cult-movie fandom.

Nevertheless, even before AnimEigo made the films available in their original form, Lone Wolf and Cub was already a familiar franchise in other media for those in the know. The original manga source material was an early candidate for English-language translation, with First Comics behind the North American publications that ran from 1987 to 1991. Even prior to this, there were many whose eyes had first been opened to the bloody exploits of Itto and his “sword and child for hire” through the legendary Shogun Assassin, a re-edited, redubbed and rescored mash-up of the first two films, deftly put together by David Weisman and Robert Houston and released by Roger Corman’s New World Pictures in 1980 to capitalise on the popularity of the same year’s adaptation of James Clavell’s Shogun.

Often denounced as the loveless bastardisation of the first two instalments, with 12 minutes of the first film integrated into its follow-up Baby Cart at the River Styx (1972), the title generally considered to be the best in the series, it is all too easy to downplay the significance of Shogun Assassin. This is especially true in the UK, where it soon became a cult classic in the new home video market for its matter-of-fact scenes of dismemberment, decapitation and delirious slow-mo arterial spurts against poetically-rendered salmon-pink sunsets. The film was driven underground, towards an arguably wider audience, when it was roped into the Video Nasties furore of the early-1980s.

Such a fate seems bewildering now. While undeniably gory, there was a lot more to Shogun Assassin than the hyperbolic bloodletting. It is worth pointing out that beyond the rarefied enclaves of London’s National Film Theatre, it was almost impossible for British viewers in the early 1980s to catch so much as a glimpse any kind of Japanese film, with video releases of even such global grandmasters as Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi a long way off.

Such a fate seems bewildering now. While undeniably gory, there was a lot more to Shogun Assassin than the hyperbolic bloodletting. It is worth pointing out that beyond the rarefied enclaves of London’s National Film Theatre, it was almost impossible for British viewers in the early 1980s to catch so much as a glimpse any kind of Japanese film, with video releases of even such global grandmasters as Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi a long way off.

Shogun Assassin might not have been the real deal, but it was about the closest we had, and stands perfectly well on its own merits. Even now it seems pointless to compare it with the original unadulterated Lone Wolf films, which at the time we never thought we would have had a cat in hell’s chance of ever seeing. Mes is clearly a fan, describing it as “a sublime piece of entertainment… so much more than just another re-dubbed martial arts actioner for the grindhouse crowd… To some it was even the start of a fascination with Japanese film.”

Indeed, it was this title that provided me with one of my early gateways, via a cherished and well-worn nth-generation video dupe acquired at some point during my teens. Even now, it is impossible for me to see so much as an image from series without the relentless chugga-chugga-chugga-chugga-da-dum-da-dum earworm of Mark Lindsay’s eastern-flavoured disco soundtrack kicking off in my head. It might seem odd that Itto and son should owe their familiarity to a film so completely differently constructed and pitched from the original source material, but it is almost certain that both manga and the original film adaptations would never have seen the light of day in the West if it weren’t for Shogun Assassin.

While Goseki Kojima’s original illustrations epitomised the new gekiga (“dramatic pictures”) style of cinematic realism that emerged in manga towards the end of the 1960s, the visual approach taken for the films deviated considerably from their visual source, unlike Toshiya Fujita’s more faithful live-action rendition of Kazuo Kamimura’s compositions for Lady Snowblood, also written by Koike. As Mes notes “the Baby Cart films derive their style less from Kojima than Misumi”, the director of films #1-3 and #5 (the fourth was directed by Buichi Saito, with Yoshiyuki Kuroda ending the series with White Heaven In Hell).

Mes’s chapter devoted to Kenji Misumi, one of the unsung heroes of Japanese cinema, is particularly welcome, detailing the evolution of a style that made much use of unfocused or under-lit foreground objects in service of overall composition, across a filmography consisting primarily of samurai-era pieces. The director, when discussed, has often been dismissed as a minor-practitioner of period-set potboilers, but it is often overlooked that Misumi was entrusted with helming Japan’s first ever 70mm movie, the religious epic Buddha (1961), the biggest-budget but also the highest-grossing production of its era.

Mes’s chapter devoted to Kenji Misumi, one of the unsung heroes of Japanese cinema, is particularly welcome, detailing the evolution of a style that made much use of unfocused or under-lit foreground objects in service of overall composition, across a filmography consisting primarily of samurai-era pieces. The director, when discussed, has often been dismissed as a minor-practitioner of period-set potboilers, but it is often overlooked that Misumi was entrusted with helming Japan’s first ever 70mm movie, the religious epic Buddha (1961), the biggest-budget but also the highest-grossing production of its era.

With regards to other changes from source to screen, Mes also points out that many of the scenes and plot elements have been shuffled, altered or omitted entirely in the process of condensing a 28-volume manga series into a six-film cinematic saga, helpfully detailing which manga episodes made it into which film in the credits section for each instalment.

There is one further irony to the original Lone Wolf series, in that while the films have now achieved iconic status with overseas fans, in Japan they have been completely overshadowed by the 78-episode NTV series broadcast between 1973-76, which was considerably more faithful to Koike and Kojima’s narrative. Apparently when the actor Kinnosuke Yorozuya was announced as the star of this new small-screen version, Wakayama was so miffed that someone else might be stepping into Itto’s shoes, he hastily put an end to the cinematic series before it reached its natural conclusion. There have since been a number of further film and TV adaptations, while Itto and son’s exploits also provided an acknowledged influence on Max Allan Collins’ 1998 graphic novel Road to Perdition, filmed by Sam Mendes in 2002.

Mes provides the context for what remains an extraordinarily powerful series of films. Other areas of interest covered are the original manga and its author, the career of Wakayama, the scandalous fate of the first screen Daigoro, Akihiro Tomokawa, and a particularly valuable chapter detailing the history and tropes that form the Tokugawa-era jidai-geki, in which it is revealed that Lord Retsudo of the Yagyu clan has his basis in a real-life historical figure, albeit a fairly obscure one. Informative and accessible across its 165 pages without being too scholarly, fans of the films and its wider universe will surely find this an enlightening accompaniment, and as good an excuse, as if one were needed, to revisit this startling series.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

Father, Son, Sword: The Lone Wolf and Cub Saga by Tom Mes is published by Arrow Books.

Leave a Reply