Books: Max Fleischer

July 31, 2018 · 1 comment

By Raz Greenberg.

76 years after they were forced out of their own studio, a move that marked the end of their prominent role in the development of American animation, the legacy of animation pioneers brothers Max (1883-1972) and David (1894-1979) Fleischer is still alive and kicking, and nowhere is this legacy more evident than in anime productions. The Fleischers’ influence runs deep within the DNA of anime: early Japanese pioneers drew a lot of inspiration from early Fleischer productions as the Out of the Inkwell shorts and the Song Car-Tunes series; references to the Fleischer brothers’ productions can be found in Mitsuyo Seo’s ambitious animated wartime propaganda epics like Sacred Sailors; there is an unmistakable Fleischer-esque touch to the character-design style of Osamu Tezuka; and the Japanese audience’s post-war discovery of the Fleischers’ studio late works – their 1939 feature Gulliver’s Travels and their Superman cartoons – played an important part in shaping anime genres, notably robot and science fiction animation.

76 years after they were forced out of their own studio, a move that marked the end of their prominent role in the development of American animation, the legacy of animation pioneers brothers Max (1883-1972) and David (1894-1979) Fleischer is still alive and kicking, and nowhere is this legacy more evident than in anime productions. The Fleischers’ influence runs deep within the DNA of anime: early Japanese pioneers drew a lot of inspiration from early Fleischer productions as the Out of the Inkwell shorts and the Song Car-Tunes series; references to the Fleischer brothers’ productions can be found in Mitsuyo Seo’s ambitious animated wartime propaganda epics like Sacred Sailors; there is an unmistakable Fleischer-esque touch to the character-design style of Osamu Tezuka; and the Japanese audience’s post-war discovery of the Fleischers’ studio late works – their 1939 feature Gulliver’s Travels and their Superman cartoons – played an important part in shaping anime genres, notably robot and science fiction animation.

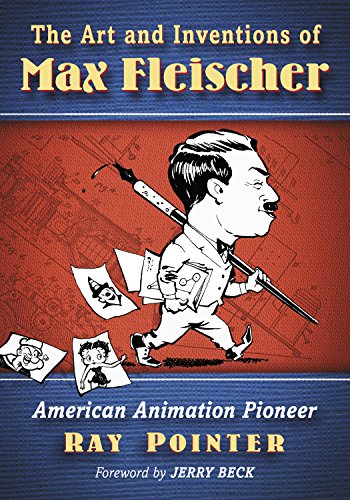

You won’t find any mention of this in Ray Pointer’s book The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer: American Animation Pioneer, which by itself isn’t a problem: the book isn’t about the Fleischers’ influence on Japan. In fact, the book isn’t about the Fleischers’ influence at all, at least not of the artistic kind. You wouldn’t find any mention of the Fleischers’ contribution to the development of the superhero genre in American comics and animation, their influence on the American underground comix movement or the inspiration they provided to many developers of digital games (from Pac-Man and Donkey Kong to the more recent Cuphead) in the book either. Which, I guess, is also fair, but it highlights the book’s biggest problem: it’s more about “inventions” and less about “art”. Pointer’s book is definitely the most detailed and richly-researched historical account of the Fleischers’ rise and fall, but it’s an account that reduces their body of work to the development of technologies, techniques and work practices. It reads more like a book about rotoscoping, sound on film, color and stereo-optics than a book about Koko the Clown, Betty Boop and Popeye the Sailor.

Which is a shame, because reading the book makes it clear that Pointer had unprecedented access to both materials and people related to the Fleischers. This serves the book best when the author dives into personal stories, beginning with the Fleischer family’s immigration to the United States, leading to the conclusion – not explicitly stated in the book but pretty obvious for anyone reading it – that both Max and David Fleischer inherited their father’s sense of technical innovation, but sadly, also his somewhat naïve attitude toward business. This is followed by the story of the Fleischers’ first forays into animation, the foundation of their studio and the professional and (sometimes rocky) personal relationships among its workers. The parts where Pointer discusses the people in the studio are among the book’s strongest; they give the readers an idea of not only what it was like to work in the emerging animation industry, but also of the many problems that plagued it, including some (like sweatshop working conditions and poor payments) that hound it to this very day. In a few instances, however, the book crosses the line from personal stories to dubious gossip – one section, for example, portrays Willard Bowsky, one of the studio’s chief animators, as an anti-Semite and possible Nazi sympathizer which I find hard to believe since Bowsky was Jewish.

Which is a shame, because reading the book makes it clear that Pointer had unprecedented access to both materials and people related to the Fleischers. This serves the book best when the author dives into personal stories, beginning with the Fleischer family’s immigration to the United States, leading to the conclusion – not explicitly stated in the book but pretty obvious for anyone reading it – that both Max and David Fleischer inherited their father’s sense of technical innovation, but sadly, also his somewhat naïve attitude toward business. This is followed by the story of the Fleischers’ first forays into animation, the foundation of their studio and the professional and (sometimes rocky) personal relationships among its workers. The parts where Pointer discusses the people in the studio are among the book’s strongest; they give the readers an idea of not only what it was like to work in the emerging animation industry, but also of the many problems that plagued it, including some (like sweatshop working conditions and poor payments) that hound it to this very day. In a few instances, however, the book crosses the line from personal stories to dubious gossip – one section, for example, portrays Willard Bowsky, one of the studio’s chief animators, as an anti-Semite and possible Nazi sympathizer which I find hard to believe since Bowsky was Jewish.

But the book’s main focus, as noted above, is the studio’s technological innovations. Pointer goes into great detail on the development and the operating principles behind the Fleischers’ contribution to animation drawing, soundtracks to musical films and three-dimensional backgrounds, and he attempts to make his descriptions as accessible possible for casual readers. I’m not sure, however, how much interest he will find among such readers; the book devotes a lot of space to technical innovations, and little feels connected to the creative work of the studio. This dry approach works against what Pointer wanted to achieve, as even when the book points to important historical discoveries, they are kind of lost in the details. One major example concerns the Fleischers’ 1926 musical cartoon My Old Kentucky Home, long believed to have preceded Disney’s 1928 Steamboat Willie as the world’s first talking cartoon. Pointer claims (although no reference is provided) that the Fleischers’ talking prologue was a later addition, shoved in after the release of the Disney film.

There are places in the book where Pointer does make attempts at artistic commentary, but they are often disappointing. A chapter devoted to an analysis of Betty Boop’s character opens with a discussion of the character as a reflection of sexual imagery of her time, but quickly turns into a discussion of censorship and dry descriptions of supporting characters. An attempt to explain what went artistically wrong with Gulliver’s Travels deteriorates into an overlong discussion of how the film could have been made better, based on production notes – one place in the book, I think, where Pointer’s access to historical materials did not work in his favour. It should be noted, however, that quotes from contemporary press reviews, spread generously all over the book, do work in giving readers an idea about the quality of different Fleischer productions and the cultural context in which they were made.

Pointer concludes with a chapter on the rather unimpressive careers of the key players in the Fleischers’ studio in the era following the takeover by Paramount and the banishment of Max and David, leading to the grim conclusion that, had it not been to the wholesale syndication of the studio’s catalogue for television broadcast, no one would remember the Fleischers today. Factually, this conclusion may be correct; artistically it misses the point. TV broadcasts of Fleischer productions did something a lot more significant than preserve their historical legacy: they kept their alternative to the Disney style and narrative alive, something which – as noted in the opening passage of this review – is still strongly felt in both American and Japanese animation.

Despite the many reservations detailed above, The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer: American Animation Pioneer remains the best book published so far about the Fleischers – but that’s mostly due to the lacklustre competition. There are only two (yes, two) other books devoted entirely to the subject: Leslie Carbaga’s The Fleischer Story from 1988 and Out of the Inkwell: Max Fleischer and the Animation Revolution published by Max’s son Richard in 2011. Both books tell the same story as Pointer, but although Carbaga’s tone is more lively (and his book more visually appealing) and Richard Fleischer provides a more personal account, neither book features the extensive research to rival Pointer’s. For those looking for a historical account of the Fleischers’ studio, Pointer’s book is the place to go. Those looking for an artistic commentary on the Fleischer productions, however, will have to look somewhere else. Several books of animation have devoted chapters to such commentary (Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice and Magic is a personal favorite of mine in this respect), but we’re still waiting for a complete book about the Fleischers that will explore their work as art, rather than history.

Raz Greenberg is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator. The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer: American Animation Pioneer is published by McFarland.

Ray Pointer

October 24, 2019 1:18 am

As author of THE ART AND INVENTIONS OF MAX FLEISCHER: AMERICAN ANIMATION PIONEER, I am compelled to respond to this objective Review. One of the many challenges in approaching this subject has been the lack of access to many supporting documents and images, which have only surfaced in recent years. While your impression is that the book omits the artistic aspect of Fleischer animation, I fear you miss the point. Max stated the "Mechanics is the art form of the 20th Century." That was the foundation of the book as stated in the beginning and how Fleischer created the art of animation. It was through technical means, which was his creative strength. Chapters are devoted to the artistic aspect including the music, voice artists, Animators, and Background Artists, with examples of art pieces and descriptions of the painting techniques used. Reference is made to the quality of the backgrounds in the black and white cartoons painted in a sepia ink wash which made them the best looking in the business and a stand out compared to Disney's black and white period. There are also inserts that display the richness of the color work as well. The kindle version is all color, which gives true display of the sepia backgrounds. Other books may have approached the artistic perspective, but this was not necessarily the purpose of my book. And while some may not be interested in the technical aspects, there is something for everyone, which is supported by 15 five star Amazon Reviews. In assembling my book, I was able to provide high quality images, many never previously pubiished including production stills and views inside the studio. Providing these things helps put the reader into the environment, giving them a feeling that they are there. That was my intention. And by doing this it was my hope that the reader would gain greater understanding. This is particularly important since many people want to know how the cartoons were made. Over the years, many have come to me for the answers. And because of this, I wrote my book because to date, most books on animation and the Fleischer subject are written by fans or researchers who lack the depth of understanding to write such a book. In their best intentions, they write their impressions and draw superficial conclusions. In order to do the subject justice a better realization of the subject needs to come from within. Writing a book about Max Fleischer and his iconic studio requires the understanding of many things. And in writing my book, I wanted to go beyond a clinicial career review and provide greater depth and understanding of the thinking and results. To do such a book requires an understanding of the histories of the World and the 20th Century, film and society, with a little understanding of psychology. We are looking a human beings with common traits, good and bad, virtues and faults. And while there was plenty of “gossip” that circulated, the reference to Willard Bowsky’s anti-Semitic attitude was collaborated by others. Many Jewish people were severely critical of their people including the Fleishcers. This was the source of the occasional inside jokes that mocked their background as covered extensively and honestly in the book. Anyone who knows me, knows that I have been associated with this subject for 50 years. When I first spoke with Max's daughter, Ruth Kneitel in 1972, she asked me why I was interested in her father's career. My response was that I always liked jigsaw puzzles. And piecing together an accurate story on Max Fleischer has been just that since so many of the details had been scattered for decades. There is also a great challenge in doing something of this nature that is based on things that happened before I was born. But having been born Mid 20th Century gave me something of an advantage since many of the key figures were sill alive when I started my research so many years ago when I first came into the business. In conclusion, I want to thank you for your objective review. It is a great challenge getting books published today, particularly anything that is not about Disney. Another challenge is that some people have expectations of what they want a book to be. Many have been surprised at what was contained in my book, while others such as yourself were looking for something else That is why there are other books. What my book does is follow the rise and fall of Fleischer Studios. People have wanted to know why it all ended. My book finally tells that based on documentation not fabrication. But the greatest challenge is in writing a book about what is essentially a moving art form. The greatness of the Fleischer Studio and its figurehead, Max Fleischer is not totally realized until it is seen. It is my hope that this book has enhanced the placement of Max Fleischer in American Culture and cinema history.