Books: Men in Metal

November 2, 2020 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Surely nothing could be less animated than a statue? But if there is anything notable in 2020 beyond pandemic and politics, it must be the power that statues have in daily life: to be ignored, to be toppled, to be replaced with images more fitting of who we want ourselves to be? Statues, for Sven Saaler of Tokyo’s Sophia University, are an intriguingly contradictory element of public life. They have a misleading permanence, and a deceptive importance – I’ve lived in the same town for ten years, but if you put me on the spot, I still couldn’t tell you the name of the statue of That Guy in the Park. I’ve never got around to reading the plaque.

Sven Saaler’s new book, Men in Metal: A Topography of Public Bronze Statuary in Modern Japan, investigates the bizarre history of public monuments, an alien concept that arrived in Japan in the 1870s along with a bunch of other foreign affectations. Returning from a grand world tour, the fact-finding Iwakura Mission reported the odd behaviour of Europeans: that you couldn’t throw a rock in a town square without hitting the image of a famous king or victorious general. Those quirky occidentals even got into fights over each other’s statues, carting them off as plunder, and installing them in their own cities as a permanent reminder of who was the top dog. Japan, it was decided, needed to do some of that.

But who should be memorialised? Saaler’s title is provocatively sexist in keeping with its subject – encouraged by the sight of public monuments in 19th century Europe, the Japanese authorities determined to establish a cult of “Great Men” in public places, honouring legendary emperors, new-era politicians and war heroes. Less than 5% of the statues in his database, reports Saaler, were of women. Although to put things in context, a similar survey of public statuary in the USA returned a statistic little better: a mere 8%.

A fight soon broke out over representations of the Emperor Meiji, whose image was considered sacred, with some pundits arguing that making a model of him and then leaving it out in the open for pigeons to shit on was not really fitting. For Michitomi Higashikuze, an aristocrat writing in 1900, bronze statues were a ridiculous European conceit that the Japanese should have no part of. For the Imperial Japanese Army, they were a chance to put up permanent reminders of who did all the hard work in Japan’s early modern wars, leading to a mushrooming of bronze princes on horseback and decorated generals. The Imperial Japanese Navy wasn’t having any of that, retaliating with statues of the people who had really sacrificed: heroic dead from the lower ranks, often memorialised in more conspicuously public places, such as train stations, where Navy recruiters hoped to encourage a sense of empathy and rapport with the common man.

Saaler’s research incorporates some great and unexpected sources, including the shuisho prospectuses drawn up to solicit donations – even in the 19th century, such statues were often crowd-funded. He also makes use of new technology, running word-searches on databases to track the number of times the press uses the term “war god” in the twentieth century. The result is an electrifying account of the politics and scandals that created so much of the imagery that now merely sits, out of focus, in the background while two primetime TV lovers share a packed lunch by a fountain.

In 1927, the inventor Isao Morioka patented an ingenious process called stereographic statuary (rittai shashinzo), in which two cameras would create a 3D blueprint for lifelike likeness of an individual, creating the opportunity for truly realistic images. It was a far cry from the statue of the rebel Takamori Saigo which still graces Ueno Park. Infamously anti-modern, the cantankerous Saigo shunned all photography, and so his posthumous image for posterity was knocked up by an artist essentially photo-fitting his brother and cousins for a rough guess. The bodge-job on Saigo, however, has endured far longer than many of his contemporaries, in part because as a rebel he was only memorialised in civilian dress. He doesn’t look like a warrior at all, he looks like a tramp in a bathrobe, walking a dog on a piece of string.

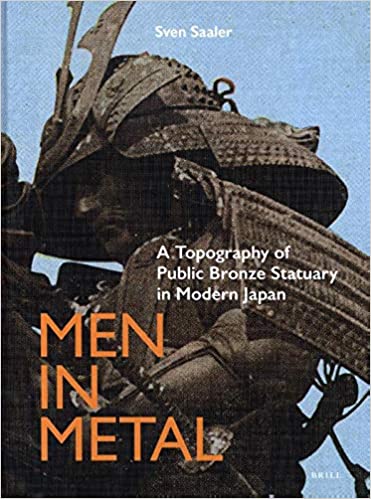

Another statue sure to be on the itinerary of any Tokyo tour is that of Masashige Kusunoki, the 14th-century samurai remembered primarily for obeying the commands of an Emperor who wouldn’t listen to reason. Ordered into a battle he knew would kill him, he did as he was told, making him a symbol of unquestioning loyalty (or if you want to be difficult, of why it’s a bad idea to listen to idiots). Kusunoki is depicted in full samurai armour, wheeling his horse for his fatal last charge, in a statue unveiled in 1900 on the outskirts of the Imperial Palace. Since there is little else to do there, it has become something of a selfie-site for thousands of tourists, many of whom do not know the story behind Kusunoki’s death, or indeed that the commission to put up his statue was backed by the Sumitomo corporation to commemorate the double centenary of its copper mines in Besshi.

Kusunoki’s statue, which fittingly graces Saaler’s cover, was a subject of some controversy in the art and historical world, but achieved new meaning in the 20th century as that of a relatively “common” soldier, given pride of place in sight of the Emperor. In particular, Kusunoki came to signify the suicidal loyalty of the kamikaze pilots, which makes it something of a miracle he wasn’t melted down and turned into cufflinks after 1945.

There are tales of corrupt officials bribing artists to have their faces used for legendary characters, and of ghastly aristocrats who get honoured for doing little more than throw their weight around, at the cost of many uncelebrated underlings’ lives. There’s politicking around the land that a statue might be sited on, and even intrigues over size. If the public purse wants to memorialise a war hero, they’ll get whatever they can afford, but so can the massive military-industrial complex that decides to honour a politician who let them ram-raid the Korean economy, and they’ve got much more money to spend. Saaler even gets to grips with an odd spin-off of public memorials – their recurring use in Japan as a place to stage a grandstanding, attention-grabbing suicide.

He is just as good on the empty plinths – statues that were melted down as part of wartime austerity measures; statues removed during the post-war US Occupation, and statues put up in what was once the Japanese Empire, but are now squirreled away in corners of national museums in Taiwan or Korea. In the case of Masatake Terauchi, the general who appropriated lands from Korean farmers and sold it to Japanese businesses, he was once commemorated in a horseback statue in Tokyo. After the war, Terauchi was toppled, and his plinth became home to a representation of the spirits of Peace, Love and Intellect, known to posterity for reasons that would soon become obvious as “The Three Naked Women.”

Saaler is resistant to propaganda and the official record – noting that public interest in the funeral of the Meiji Emperor was so low that his mourners were outnumbered by his honour guard. He ends by tying the choices of statues in public places to a related issue – school textbooks that get to rule on who the great people of history are, itself a subject of some controversy in Japan. He points out, for example, that a statue of the legendary Yamato Takeru is one thing, but including him in a children’s book of “great Japanese” is tantamount to suggesting that the imperial family really were sent from space by the Sun Goddess.

Saaler’s post-war chapter deals with the political umming and ahhing about whom to commemorate in the 21st century, including Mother Teresa, a gaggle of sportsmen, and a whole bunch of samurai-of-the-moment, depending on the year’s NHK Sunday-night drama series. He also picks out some real oddities, like a statue of Ataturk, installed at a theme park that went bankrupt, toppled by an earthquake, and moved to a place where something vaguely Turkish had once happened. But there appears to be no mention in his book of Hachiko, the loyal dog whose somewhat apocryphal vigil for his dead master’s return is celebrated outside Shibuya station. Nor does he engage with some of the most conspicuous bronzes of the last decade: the fan-bait anime and manga figures, such as the Shigeru Mizuki characters dotted all around the artist’s home town of Sakaiminato, or Astro Boy, who greets visitors to Nerima. True enough, these are not the “Great Men” whose rise and fall is the main focus of Saaler’s investigation, nor are many of them even human, but I feel that, too, is a point worth raising – that in the absence of yesterday’s heroes, corporate interests and tourist boards are raising graven images to imaginary robots and aliens.

As for the pigeons, it wasn’t until 2003 that Yukio Hirose, a professor in Kanazawa, analysed the alloy of a statue in his prefecture, and determined that it contained an unusually high quality of arsenic, which seemed to have deterred the local birds from using it as a toilet. For this discovery, he was given an award by the Annals of Improbable Research.

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Short History of Tokyo. Men in Metal by Sven Saaler is published by Brill.

Leave a Reply