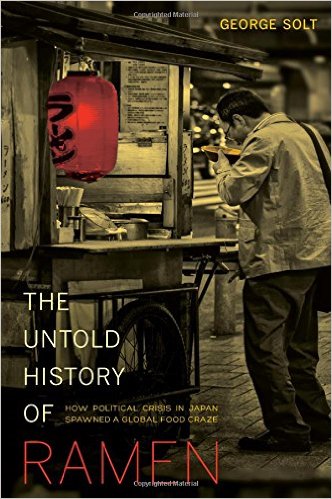

Books: The Untold History of Ramen

September 3, 2016 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

In The Untold History of Ramen, George Solt digs behind invented traditions to tell the story of one of Japan’s most famous dishes, not as a breathless account of urban cuisine, but a hard-nosed anaylsis of demographic changes, supply chains and industrial politics.

In The Untold History of Ramen, George Solt digs behind invented traditions to tell the story of one of Japan’s most famous dishes, not as a breathless account of urban cuisine, but a hard-nosed anaylsis of demographic changes, supply chains and industrial politics.

Although Solt notes the existence of noodle dishes in Japan from earlier times, he focuses on the interaction between Japan and its colonial workforce, as Koreans, Taiwanese and mainlanders push an idiosyncratic idea of “Chinese” food to Japanese urban populations. The name ramen is adopted for political reasons, after street vendors in Sapporo tire of being asked for “Chinky” noodles. The word for “China” in the dish’s name itself becomes politically loaded, not only as a springboard for casual racism, but because the original term Chuka implied that China was the Middle Kingdom and the centre of the world (an unwelcome assertion for imperialist Japanese), and the new term Shiina was discouraged for itself being racist.

In the post-war period, American food aid (which the Japanese eventually had to pay for) arrives in the form of shiploads of wheat. The Japanese, starved of rice, turn to noodles, while black marketeers with access to meat and lard push ramen as a hearty dish for the working man. There are illuminating accounts of the appearance and meaning of instant noodles in films, print and advertising, tracking their rise from a stopgap measure for the hopeless bachelor (Leiji Matsumoto’s Otoko Oidon) to a gourmet affectation by foodies (Juzo Itami’s Tampopo, pictured above), and, supposedly, a status as Japan’s national dish. Solt also charts the attempts by local councils to foster food-based tourism, with the often arbitrary creation of regional variations, as well as some entertainingly sexist campaigns against “lazy” housewives, who not only make the mistake of embracing instant food, but then use the time they save in a fashion that is not approved by the patriarchal establishment.

In the post-war period, American food aid (which the Japanese eventually had to pay for) arrives in the form of shiploads of wheat. The Japanese, starved of rice, turn to noodles, while black marketeers with access to meat and lard push ramen as a hearty dish for the working man. There are illuminating accounts of the appearance and meaning of instant noodles in films, print and advertising, tracking their rise from a stopgap measure for the hopeless bachelor (Leiji Matsumoto’s Otoko Oidon) to a gourmet affectation by foodies (Juzo Itami’s Tampopo, pictured above), and, supposedly, a status as Japan’s national dish. Solt also charts the attempts by local councils to foster food-based tourism, with the often arbitrary creation of regional variations, as well as some entertainingly sexist campaigns against “lazy” housewives, who not only make the mistake of embracing instant food, but then use the time they save in a fashion that is not approved by the patriarchal establishment.

The story of ramen is dominated by Momofuku Ando, the “inventor” of instant noodles and the head of the Nissin corporation that remains the largest player in the industry. This, at least, is the story as told by Nissin’s own publicity. But while Solt acknowledges Ando’s importance, he also points to numerous elements that are less widely known, such as Ando’s Chinese origins (he was born in Japanese-occupied Taiwan, where his original name was Wu Baifu), and the possibility that he chose the name Nissin as a form of false advertising, to associate his company with the longer-established Nissin flour corporation. It’s Ando who approaches government representatives to argue that the US-derived focus on wheat products is going to destroy Japanese culture unless they find some more “Asian” application than making bread and biscuits. It’s Ando who pushes a marketing scheme to persuade consumers that noodles are not only traditional but also healthy – a claim made until the mid-1960s. He is also responsible for a ruthless branding enforcement exercise against potential competitors. In a microcosm of so many other narratives of Japanese industry, Nissin is not even the first company to sell the dish, but it is the most successful at snatching patents for the various parts of its process, and suing its rivals out of business.

Solt’s narrative offers a bottom-up account of the post-war Japanese economy, spreading out from the humble noodle to embrace changes in labour patterns, fashions, and trends. Beyond the popular imagery of teeming hordes of salarymen, he notes the rise in the 1970s of datsu-sara – men who give up on the rat race to seek a more artisanal and personally satisfying career, perhaps as a noodle seller or small café owner. By the 1990s, the new watchword is risutura (short for restructuring), a euphemism for the mass redundancies that characterised the end of the bubble economy, leading to articles in the press not about the attractiveness of a career in noodles, but of the harsh realities of starting a small business.

If there is anything that has slipped through Solt’s rigorous net, it is the consideration of how unhealthy instant noodles might be. It would have been interesting to read an account of the fluctuating fortunes of monosodium glutamate, that much-maligned, much-misunderstood salt that forms the foundation of so much oriental cookery. But that, perhaps, is another book in itself.

Jonathan Clements is the author of The Emperor’s Feast: A History of China in Twelve Meals.

Leave a Reply