Books: Promiscuous Media

January 9, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

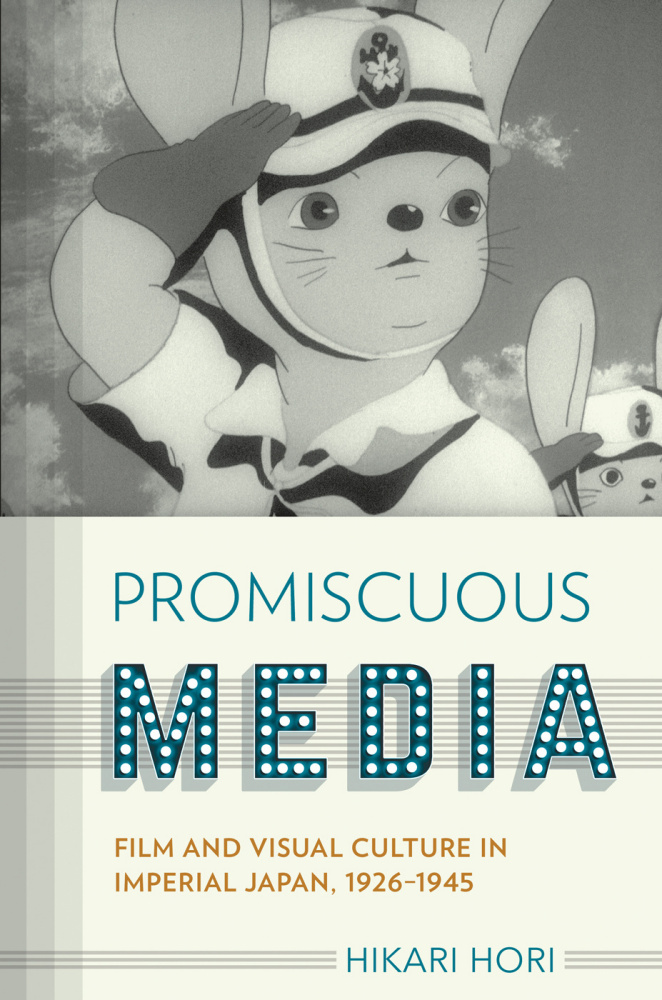

Hikari Hori’s new book Promiscuous Media: Film and Visual Culture in Imperial Japan 1926-1945, examines the first phase of the Showa Era, from the enthronement of Emperor Hirohito through to the end of World War Two. She offers an enthralling narrative of Japan’s first mass-media sovereign, but also the theories and critical arguments that sprang up over the uses of propaganda and censorship, in photography, film-making, magazines and animation.

Hikari Hori’s new book Promiscuous Media: Film and Visual Culture in Imperial Japan 1926-1945, examines the first phase of the Showa Era, from the enthronement of Emperor Hirohito through to the end of World War Two. She offers an enthralling narrative of Japan’s first mass-media sovereign, but also the theories and critical arguments that sprang up over the uses of propaganda and censorship, in photography, film-making, magazines and animation.

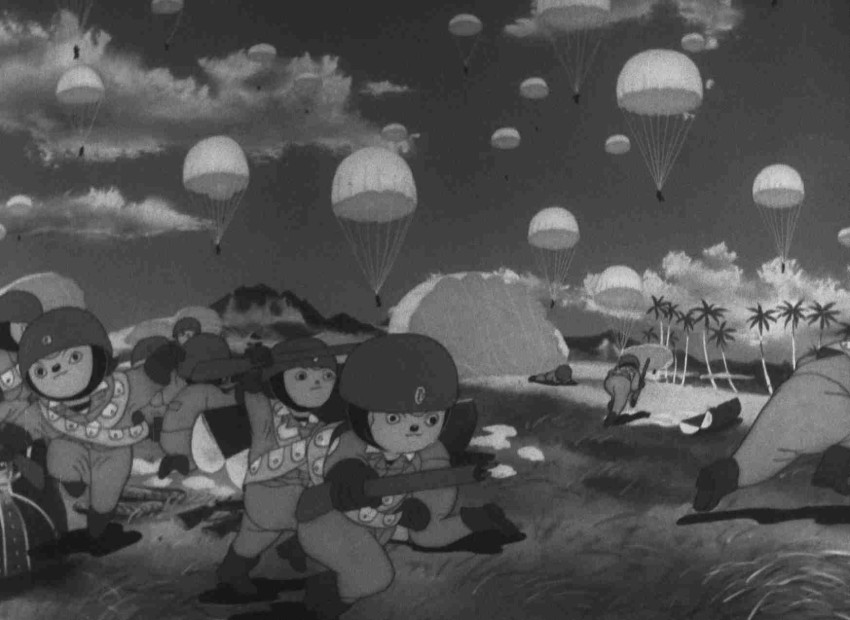

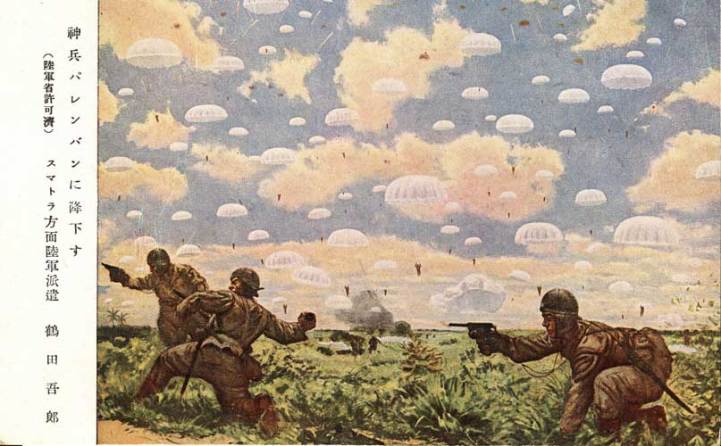

It’s easy to forget, in an age where everybody has a television in their pocket, that in days gone by the media experience, even of cinema, often revolved around still images. There was no giggling over YouTube in 1943 – unless you were sitting in the cinema itself, personal reveries about favourite stars or thrilling scenes often meant staring at a poster or a photo. Osamu Tezuka famously extrapolated his entire Metropolis not from seeing Fritz Lang’s namesake film, but from a couple of pages in a magazine. Hori extends this sensibility throughout Japanese culture, settling on the most memorable images that remained after audiences saw particular films. Mitsuyo Seo’s cartoon Sacred Sailors is hence particularly interesting to her, because it references iconic moments from wartime culture, including romanticised imagery of paratroopers and the fall of Singapore.

It’s easy to forget, in an age where everybody has a television in their pocket, that in days gone by the media experience, even of cinema, often revolved around still images. There was no giggling over YouTube in 1943 – unless you were sitting in the cinema itself, personal reveries about favourite stars or thrilling scenes often meant staring at a poster or a photo. Osamu Tezuka famously extrapolated his entire Metropolis not from seeing Fritz Lang’s namesake film, but from a couple of pages in a magazine. Hori extends this sensibility throughout Japanese culture, settling on the most memorable images that remained after audiences saw particular films. Mitsuyo Seo’s cartoon Sacred Sailors is hence particularly interesting to her, because it references iconic moments from wartime culture, including romanticised imagery of paratroopers and the fall of Singapore.

The most iconic image of all, of course, is that of the Emperor Hirohito, the subject of pious veneration. After stories started to crop up of people killed retrieving the Emperor’s portrait from burning buildings and flooded houses, writers as early as 1896 pleaded with the public to understand that a human life was worth more than a mass-produced image, regardless of who it depicted. Kiyoshi Watanabe, a sailor on the sinking battleship Musashi, later wrote bitterly of his crewmates risking their lives and compromising their swimming ability, merely to fish a portrait out of the main battery control room. Hori takes the narrative of Hirohito’s image all the way through the war, to the peacetime replacement of the military Emperor with a man in a morning suit, and the equally iconic two-shot of the shrunken Hirohito standing beside his replacement as the “ruler” of Japan, General Douglas MacArthur.

With a background both in visual culture and gender studies, Hori devotes a sizeable portion of her work to the role of women, both as memorable figures in iconic movements, and as the curators of photographs, including the devout mother who would always cut out and save the pictures of the Emperor from old newspapers before she threw them away. She offhandedly notes that the Japanese were led to believe that American women formed part of the crews of the B29 bombers overhead – an oddly feminist propaganda message, designed to push Japanese womenfolk into a greater involvement in the war effort.

Hori aligns herself with the Japanese historian Takahisa Furukawa, who questions whether the general population were all that keen on the propaganda films themselves – “national policy movies” in wartime Japan were those films that were so breathlessly gung-ho that they weren’t charged a censorship fee; audiences, however, weren’t necessarily ready to swallow all the oh-what-a-lovely-war messages that were thrown at them. Before the war, she adds, cinemas were apt to favour Mickey Mouse over home-grown animation because the Disney cartoons were cheaper. Hori healthily questions the contemporary media reports of “spontaneous” rounds of applause, ovations and national anthem sing-a-longs and even quotes from dissenters. Most notable among these is Tsuneo Hazumi, a film critic who dared to write in 1942: “I cannot hate the dreams of Snow White, even as I hate the violent country of America.”

Hori aligns herself with the Japanese historian Takahisa Furukawa, who questions whether the general population were all that keen on the propaganda films themselves – “national policy movies” in wartime Japan were those films that were so breathlessly gung-ho that they weren’t charged a censorship fee; audiences, however, weren’t necessarily ready to swallow all the oh-what-a-lovely-war messages that were thrown at them. Before the war, she adds, cinemas were apt to favour Mickey Mouse over home-grown animation because the Disney cartoons were cheaper. Hori healthily questions the contemporary media reports of “spontaneous” rounds of applause, ovations and national anthem sing-a-longs and even quotes from dissenters. Most notable among these is Tsuneo Hazumi, a film critic who dared to write in 1942: “I cannot hate the dreams of Snow White, even as I hate the violent country of America.”

Animation forms a crucial component of Hori’s book – a fair reflection not of mere scholarly bias, but of a contemporary sense of its transnational value. No less a figure than the film theorist Taihei Imamura argued that animation and newsreels should form the prime media unleashed on Japan’s South Sea colonies, to soften them up for acculturation. Animation hence gets an entire chapter to itself regarding the attempts to form a uniquely Japanese style. In this, Hori cites both the wonders of Disney and the glove thrown by the Wan Brothers with their Princess Iron Fan in China, which already established a bunch of specifically “Chinese” tropes. She notes that when Princess Iron Fan was screened in Japanese cinemas, it was shown on a double bill with the paratrooper documentary Divine Sky Warriors, perhaps explaining why animation and paratroops might occur to the Navy as a reasonable subject for Japan’s first feature-length cartoons.

Hori also takes the time to berate certain modern scholars for suggesting, a little bit too hopefully, that Sacred Sailors smuggles in a pacifist message. She goes on to point out the value of animation and special effects work in the mythologising and reporting of Japan’s war efforts – although Japanese camera footage does survive of the Pearl Harbor attack, it is barely thirty seconds long, shaky in the extreme, and at one point even turns upside-down. Model work or animation was hence the only way to dramatically recreate Japan’s victories for a home audience, and the footprint that animation enjoys in this book is a fitting assessment of its power and impact in the 1940s.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Sacred Sailors: The Life and Work of Seo Mitsuyo.

anime, books, cinema, HikarI Hori, Japan, Jonathan Clements, Momotaro, propaganda, Sacred Sailors, WW2

Leave a Reply