Books: Reading Murakami

March 19, 2021 · 1 comment

By Jonathan Clements.

Almost everything that is written about fiction is either reception (what the reader thought of the book) or production (an occasional making-of about the author at work). David Karashima’s book Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami is dedicated to areas that hardly anybody ever talks about – the way that the works of Haruki Murakami were edited, translated and marketed in the English language, in everything from discussions of the implied reader to the cover designs. He foregrounds a dozen unsung heroes of publishing: translators, editors and agents, as well as artists and publicists, all of whom toiled behind the scenes for years to create Murakami’s “overnight success.”

Murakami is a critical figure in our understanding of popular culture over the last thirty years, and not merely in Japan, where he has been an obvious inspiration for the works of Makoto Shinkai. He has stimulated numerous pastiches and remakes elsewhere – he was a heavy influence on Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, and has been adapted for the Thai cinema. His books not only entertained a whole generation of readers with their ruminative, slacker, hipster anti-heroes, but now have a sort of sonic boom, as a new generation repackages their themes for younger readers who might never have heard of him. That’s the only excuse, anyway, I can come up with for I Want to Eat Your Pancreas.

I have this theory that your first Haruki Murakami book is your best. Whatever it is about his work that bewitches readers all around the world, the first kick in the eyeballs is the one you cherish the most. And for me it was Pinball 1973, acquired in the Japan-only Kodansha English Library edition at a bookshop in Osaka, I became something of a Murakami evangelist that year, creating several new fans of his work at my college, one of whom would turn up seventeen years later and present me, by way of thanks, with a copy of A Wild Sheep Chase that he had got the author himself to autograph. Back in England in the mid-1990s, I found myself writing the book pages for Anime UK magazine, and pushing a number of authors from Kodansha International who seemed to be on the cusp of stardom.

Something I never really thought about at the time was the sheer gamble underway, as a Japanese publisher threw money at foreign-language editions that stood little obvious chance of selling abroad to the degree they did in Japan. But that’s just one of the elements that makes Karashima’s book such a delightful analysis not merely of works of fiction, but the world in which they flourish. Karashima is particularly good on the rising-yen dividends, as Japan’s 1980s bubble economy left vast amounts of money sloshing around the system. I vividly remember Kodansha International’s swish London offices on the Kingsway, and their lavish hardback editions of new Japanese translations, intended really to make reviews editors and foreign rights buyers think that new Japanese authors were substantially more sellable and biddable than they really were.

Murakami himself barely shows up at all – Karashima does interview him about the events in the book, but in that most Murakami-esque of touches, this is essentially a book that plots a course around a Murakami-shaped hole. Instead, it deals with the editors and marketers in Tokyo and New York, as they try to work out what constitutes decent sales for a hardback novel by an unknown foreign author. When Murakami does comment, half the time he is pulled up by an editorial aside telling him that he has got his facts wrong.

Pinball 1973, my first and favourite, was not included in Murakami’s early US publications. Kodansha led with A Wild Sheep Chase, technically the third book in a quartet of which Pinball 1973 was the second. In keeping with a US publisher’s desire to make the book more accessible, and to sound more contemporary to American readers, translator Alfred Birnbaum snipped out a bunch of references to the 1970s, at the time with Murakami’s assent.

I met Alfred Birnbaum once, in a Spanish restaurant on Charing Cross Road, where we were both visitors to the ever-changing salon of Kazuko Hohki from the Frank Chickens. I remember him as being a quiet and diffident man, his finger stuck into the pages of a Burmese paperback, as if any moment he might return to perusing squiggles even stranger than Japanese. There was a Japanese woman with us, whose name escapes me, but I think she was something in the artworld, and infuriatingly infantile. Suddenly, without warning, Birnbaum pulled his spectacles askew, like Eric Morecambe, and everybody laughed.

That paragraph you’ve just read doesn’t really help with this article. It’s self-indulgent and frankly redundant. A good editor would have snipped it away. [Sorry – Ed.] And it’s ideas like this, that a text can be improved by what is left out, that has become a fundamental feature of Murakami studies, as translators stroke their chins and cock their heads, and try to work out what might need to be sanded down for a foreign readership.

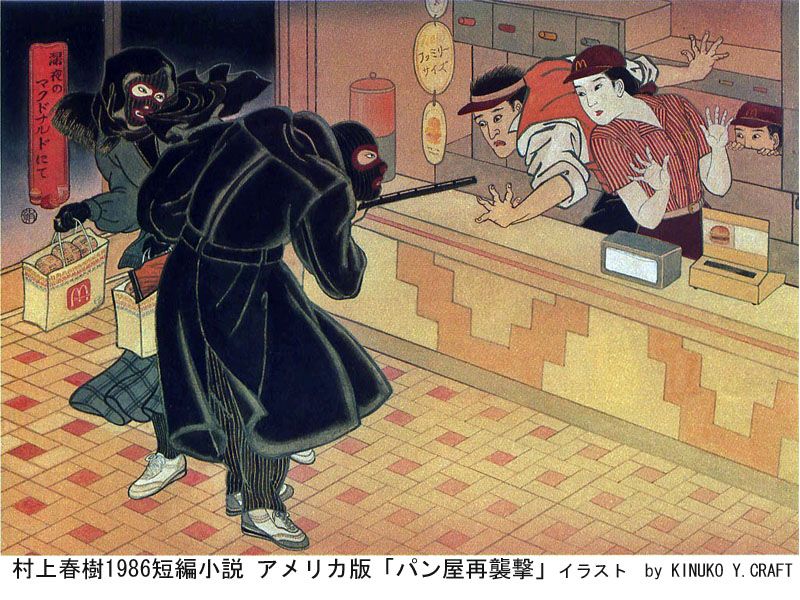

There are fascinating commentaries about the degree to which erotic elements were toned down in Murakami’s magazine short fiction in English – one wonders why the racier stuff didn’t end up in Playboy, which did after all publish “A Second Bakery Attack” in the January 1992 issue, accompanied by a fantastic ukiyo-e style double-page illustration by Kinuko Y. Craft. I remember this because January 1992 was the month I first arrived in Japan, along with a parcel from my classmate Jason’s racist school chums in America. Hearing that he had a Japanese girlfriend, they had sent him the issue, so he could get a look at the chesty Swedish women’s volleyball team or something, and “see what he was missing.” My classmates and I, however, fell upon the Murakami short story, proclaiming earnestly to each to other that the articles were really very good!

There I go again, off on a tangent. A good editor would have dumped that. [Sorry, again – Ed.] Or maybe he would have kept it, as an excuse to run the Craft illustration as a leader image, and to Google the Swedish women’s volleyball team. But as Karashima discusses, some of Murakami’s work similarly wanders off into little cul-de-sacs, that are quite normal in Japanese fiction but can seem self-indulgent and faffy in English. It might even be the case that the editorial scrutiny brought by a translator might even “improve” his works in their English editions.

“A Second Bakery Attack” was the first Murakami story to appear in print translated by Jay Rubin, marking a huge fissure in the story of Murakami translation. Thereafter, Birnbaum was edged out of the picture, and Rubin took over, ostensibly because he was more faithful to the originals. Karashima is deftly diplomatic in dealing with this issue, taking great pains to point out the Birnbaum’s late-period Murakami novel, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, was translated in collaboration with Murakami, whereas there are many redactions and alterations to be found in Rubin’s work. Rubin himself comments that many readers of Murakami can’t have an opinion on the Japanese original, and base their assessment on the false equivalence of how well the English reads. And this is really the crux of Karashima’s book. Who are we reading when we read Murakami?

I am forever in the Birnbaum camp, but that’s because my first Murakami book was his first Murakami book, too, yet I have met countless people whose first Murakami was a Rubin work, and did not love him any the less for it. Others, still, prefer Philip Gabriel, or Ted Goossen, or whoever.

Murakami is flexible when dealing with foreign publishers. If the editor of the New Yorker asks for a dozen changes to help a story read better in English, he waves them all through, but reserves the right to revert them all when a story is published in volume form. Or in other words, Murakami is different, yet again, if you read him in raw Japanese, in a particular magazine, or in a later anthology. Some short stories, such as his immensely influential “On Meeting My 100% Woman One Fine April Morning” have been translated more than once. Not even Murakami can make up his mind; his first ever short story, “A Slow Boat to China”, exists in three different versions, all written by Murakami himself!

Soon, Murakami ditched Kodansha International in favour of a lucrative offer from the New York publishing house Knopf. Murakami’s jump to Knopf, in fact, is the true threshold between his early and later publishing works. He began to change as an author, leading all parties concerned to suggest that the break with Birnbaum was by mutual consent – Birnbaum burned out and wanting to take a break from translation (which he thought would be temporary, but led to him being ghosted by all parties… except Murakami himself, who was a guest at his wedding); Murakami moving away from his pop-art early works to more mature works with a different sensibility, and other translators like Rubin and Gabriel ready to jump in.

Karashima himself observes how odd this situation is – that the launch vehicle for Murakami’s worldwide fame was arguably built on the skills and style of translators and editors who have since been scrubbed out of the picture. In some cases, such as Norwegian Wood and Pinball 1973, their works have even been taken out of print to be replaced by new versions from the new guard.

Karashima then moves on to the (possibly) different Murakami that has been published since, focusing on the editorial and translation decisions made over The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, a big, bloated thing that I confess I have never finished, although friends of mine, who read it first, say it is the best Murakami they have ever read. It’s not even unabridged – in a move that will keep academia busy for years, Rubin has donated his full-length translation, before editors got to work, to the Lilly Library in America, and it will be available to researchers for comparison in 2026.

Karashima also interviews a number of contemporary authors whose own work has been heavily influenced by Murakami in translation. The result is a fascinating, quirky and refreshingly unique account of an area that is so rarely discussed – texts in their contexts.

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of Japan. David Karashima’s book Who We’re Reading When We’re Reading Murakami is published by Soft Skull Press.

Shiroi Hane

March 22, 2021 1:11 pm

> it’s ideas like this, that a text can be improved by what is left out, that has become a fundamental feature of Murakami studies, as translators stroke their chins and cock their heads, and try to work out what might need to be sanded down for a foreign readership. This is quite timely with the current furores over Seven Seas’ editorialisation of light novels. I’ve long held that both the Mahouka and A Certain Magical Index novels would have benefited from a lot of editing down for readability, but would prefer that to happen on the Japanese side.