Books: The Art of Nausicaa

June 28, 2019 · 0 comments

By Raz Greenberg.

With the release of The Art of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind: A Film by Hayao Miyazaki, Viz has now published all of the art books that document the work on the Studio Ghibli films directed by Miyazaki – sadly, no art book has ever been published on his debut feature The Castle of Cagliostro. Collectors will certainly rejoice, but does the book hold any kind of interest for the average Miyazaki fan?

With the release of The Art of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind: A Film by Hayao Miyazaki, Viz has now published all of the art books that document the work on the Studio Ghibli films directed by Miyazaki – sadly, no art book has ever been published on his debut feature The Castle of Cagliostro. Collectors will certainly rejoice, but does the book hold any kind of interest for the average Miyazaki fan?

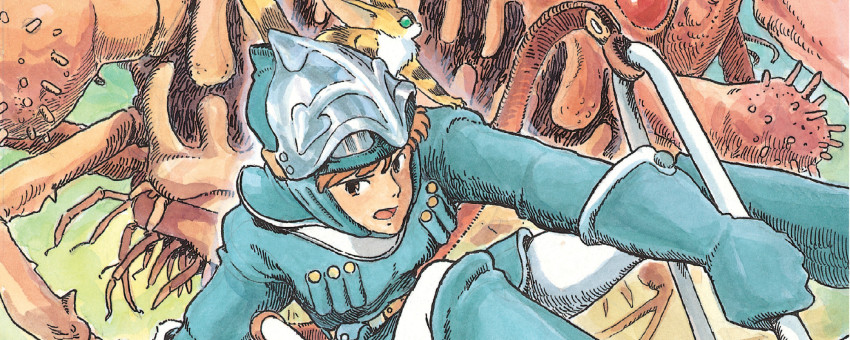

Nausicaa is a problematic choice in a way, not the least because it was never a “Ghibli” film, but if there is one Miyazaki work that has been the subject of endless public discussions already, Nausicaa is it. As early as 2007, Viz released The Art of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind: Watercolor Impressions, which focused mostly on the original manga, but also touched up the film’s production. Then there are the giant volumes Starting Point and Turning Point containing hundreds of pages of interviews and background materials related to both the film and the manga. Could The Art of Nausicaa really bring something new to the table?

Happily enough, yes. Though at times it feels more like a supplement to the aforementioned publications, readers will find a lot of new information here, related to both production and the film’s narrative.

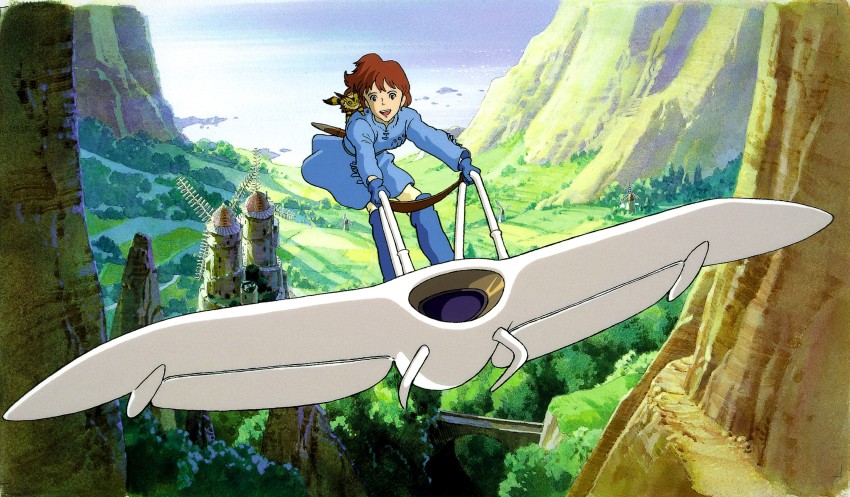

As with the previous Art of books, the bulk of the book is devoted to concept art juxtaposed with frame images from the film itself. But unlike its predecessors, there is almost no commentary that accompanies either, other than a brief description (“Nausicaa inside the Sea of Decay”, “Rifle Firing”), so readers are left to draw their own conclusions. There’s a lot to admire, from a photograph of the original weaving of the tapestry seen in the film’s opening credits (yes, it was actually handwoven) to the concept art related to the Sea of Decay, echoing the works of Roger Dean and even Max Ernst, emphasizing just how different Nausicaa is within Miyazaki’s overall body of work. The biggest treat is in the earliest chapter, where sketches for two pre-Nausicaa projects are revealed: Rowlf – an attempted adaptation of the fantasy comics by American artist Richard Corben and Warring States Demon Castle – a period piece, which I believe, is mentioned in this book for the first time. No text accompanies the images, so it’s hard to determine what belongs to each project, but I assume the impressive painting of a warrior girl riding on the back of a dragon is from the latter.

As with the previous Art of books, the bulk of the book is devoted to concept art juxtaposed with frame images from the film itself. But unlike its predecessors, there is almost no commentary that accompanies either, other than a brief description (“Nausicaa inside the Sea of Decay”, “Rifle Firing”), so readers are left to draw their own conclusions. There’s a lot to admire, from a photograph of the original weaving of the tapestry seen in the film’s opening credits (yes, it was actually handwoven) to the concept art related to the Sea of Decay, echoing the works of Roger Dean and even Max Ernst, emphasizing just how different Nausicaa is within Miyazaki’s overall body of work. The biggest treat is in the earliest chapter, where sketches for two pre-Nausicaa projects are revealed: Rowlf – an attempted adaptation of the fantasy comics by American artist Richard Corben and Warring States Demon Castle – a period piece, which I believe, is mentioned in this book for the first time. No text accompanies the images, so it’s hard to determine what belongs to each project, but I assume the impressive painting of a warrior girl riding on the back of a dragon is from the latter.

After the chapters concerning early concept sketches and the tapestry, the book’s images section is divided into chapters devoted to the different locations seen in the film. Each chapter opens with a short description of the location it examines, for example:

“A vast desert sits between the Sea of Decay and the Valley of the Wind. It is here that Nausicaa is reunited with Yupa when he is being chased by an Ohm. Anti-insect towers have been built in the desert to prevent the entry of insects from the Sea of Decay into the Valley of the Wind. The windmills attached to the tops of the towers make a curious noise when they spin, keeping the insects away to create a kind of safe zone.”

People who saw the film (and I believe 100% of the book’s readership falls within this category) will, of course, remember Nausicaa’s faithful encounter with Yupa in the desert, but the book’s description of the area – which the audience is exposed to for only a brief sequence – gives it a far more nuanced feeling.

The sketches and images section is followed by a technical chapter, mostly devoted to the different photographic effects in the film. This chapter is mostly of historical value, showing how things were done in the age of pre-digital filmmaking. Though I suspect most readers will skim through the various technical details, those willing to dive in will find new points for appreciation of the film’s staff hard work – for example, the huge amount of time and effort required just to show the small spores in the cave at the beginning of the movie.

The sketches and images section is followed by a technical chapter, mostly devoted to the different photographic effects in the film. This chapter is mostly of historical value, showing how things were done in the age of pre-digital filmmaking. Though I suspect most readers will skim through the various technical details, those willing to dive in will find new points for appreciation of the film’s staff hard work – for example, the huge amount of time and effort required just to show the small spores in the cave at the beginning of the movie.

The book’s final chapter, titled “The Road to Nausicaa”, written in a single-person’s voice but credited collectively to “Animage Editorial Division”, is perhaps the book’s biggest and most pleasant surprise. It tells the story of the film’s production, from the initial publication of the manga through the different attempts at adaptation to the film’s completion. This isn’t the first time this story has been told, of course (the most recent account in English was in Toshio Suzuki’s book Mixing Work with Pleasure), but it provides a fresh perspective. Reading the initial critical reactions to the publication of the manga, for example, is pure joy, especially the reaction from a young Katsuhiro Otomo:

“The excellence of Miyazaki’s art isn’t simply in the expressiveness of the faces of his characters, or in his ability to capture a scene in a sketch; he understands how to show off an image. Why on earth is it that this essential pleasure of manga – something manga seems to have lost lately – comes through in the work of people who have worked in anime?”

One could imagine that “showing off an image” is exactly what Otomo had in mind when he started working on his own manga opus, Akira around the same time, not to mention the extravagant anime film adaptation he released six years later. Well, now we know what gave him inspiration.

The Art of Nausicaa provides a fun reading experience which in many ways attests to Miyazaki’s talent – having read the manga and watched the film more times than I can remember, I still want more of the incredible world that Miyazaki has created in both. Here’s hoping that Viz will decide to keep the Studio Ghibli Library series active – there’s more to discover about the studio’s work beyond its films.

Raz Greenberg is the author of Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator. The Art of Nausicaa is published by Viz.

Leave a Reply