Books: Toshio Suzuki

May 13, 2018 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

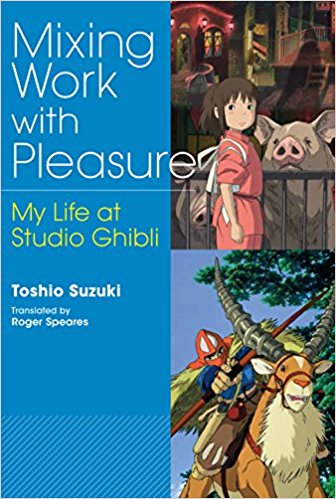

Toshio Suzuki is the most famous producer in anime, and the third most important figure in Studio Ghibli’s history, behind only Miyazaki and Takahata. Now, with absolutely no fanfare, an English translation of Suzuki’s memoir Mixing Work With Pleasure has been published by the Japan Library imprint, translated by Roger Speares.

Toshio Suzuki is the most famous producer in anime, and the third most important figure in Studio Ghibli’s history, behind only Miyazaki and Takahata. Now, with absolutely no fanfare, an English translation of Suzuki’s memoir Mixing Work With Pleasure has been published by the Japan Library imprint, translated by Roger Speares.

At 230 pages, it’s much slimmer than Starting Point or Turning Point, the two Miyazaki essay collections translated by VIZ Media. But for serious Ghibli fans or scholars, Suzuki’s book is a must-buy, both for its wealth of information and for its new perspective on a familiar history from someone who was there, beside Miyazaki and Takahata, from Nausicaa in the 1980s to Ghibli’s projects today. This edition is sombrely timed, given Takahata’s passing, but it’s a wonderful resource.

Born in 1948, Suzuki grew up before industrial anime; his first career, in the 1970s, was in journalism. For example, he wrote about Japan’s motorbike gangs, the Bosozoku, who would inspire Akira. He edited a magazine supplement about manga, meeting the likes of Tezuka and Shotaro Ishinomori (Cyborg 009). It was published by a company that Ghibli fans should recognise – Tokuma Shoten.

Suzuki’s superior at Tokuma, Hideo Ogata, landed Suzuki with a ludicrously short-notice assignment – to edit Japan’s first magazine about anime. Animage was launched in 1978, when the big thing was Yamato. But Suzuki had 118 pages to fill and decided on a “retro” article about a past classic. Not knowing anything, he was tutored on anime by a schoolgirl. She told him about an “absolutely fantastic” old film called The Little Norse Prince, aka The Great Adventure of Horus. Made in 1968, it was the first feature to involve Takahata, who directed it, and Miyazaki.

That led to an amusingly disastrous first contact. Suzuki rang Takahata for a few quotes about Prince. Takahata talked at him for an hour, explaining why he couldn’t give an interview. Then he passed Suzuki over to Miyazaki, who said he had tons to say about Prince, but wanted double the pages. “What a strange pair of characters!” Suzuki thought. Later, when he finally caught Prince, he thought the “village fights warlock” story was a brilliant Vietnam allegory.

Suzuki slowly broke the ice with the two challenging geniuses. He sat for hours beside an annoyed Miyazaki while the director drew storyboards for Castle of Cagliostro – specifically, the boards for a rather famous car chase. Suzuki also irked Takahata, working on Chie the Brat, by asking him, “After producing Heidi, how can you do a film about a girl cooking giblets on skid row?”

Somehow Suzuki ended up befriending them both. He took lightning notes on their endless conversations (“Miyazaki spoke very rapidly; Takahata invariably went on for three hours”). He read up on the film critics they loved: Andre Bazin (a favourite of Takahata) and Donald Richie. Suzuki argued more with Takahata about Chie the Brat, and was amazed when Takahata thanked him when it was finished. Years later, Miyazaki commented that the trio got on so well because their relationship was based not on fawning respect, but on trust and frankness – plus, Suzuki adds, a tendency to forget quarrels.

By 1982, Suzuki was serialising Miyazaki’s comic Nausicaa in Animage. At the start, Miyazaki showed him three styles for the strip. One was drawn in the hyper-dense, monochrome style we know. Another was far less detailed, described by Miyazaki as “in the style of Leiji Matsumoto,” and the third was something between. The “dense” version would take a day to draw one page; with the “light” version, Miyazaki could bomb through 24 pages a day. Suzuki chose the dense version; he was prepared to take chances.

By 1982, Suzuki was serialising Miyazaki’s comic Nausicaa in Animage. At the start, Miyazaki showed him three styles for the strip. One was drawn in the hyper-dense, monochrome style we know. Another was far less detailed, described by Miyazaki as “in the style of Leiji Matsumoto,” and the third was something between. The “dense” version would take a day to draw one page; with the “light” version, Miyazaki could bomb through 24 pages a day. Suzuki chose the dense version; he was prepared to take chances.

Nausicaa, of course, was soon a film, directed by Miyazaki and produced by Takahata. Getting Miyazaki to direct was hard enough; getting Takahata to produce was murder. After Takahata steadfastly refused, Miyazaki ended up chugging sake in a bar, telling Suzuki tearfully, “I devoted my youth to Takahata, but he has never done anything for me!” Suzuki finally shouted Takahata into submission. Ironically, Takahata proved to be a brilliant producer – icily logical and meticulous, especially with budgets. It was a jaw-dropping contrast to his chaotic time management when he wore a director’s hat.

The book moves into the history that fans will know. The studio was founded in 1985, and Suzuki helped there, at first without an official job title (he made his own business cards). The biggest film-related revelation concerns Miyazaki’s Totoro. It turns out Miyazaki originally planned to introduce the nature spirits at the start of the film; this would have been utterly different from the classic we know, with its wonderful pastoral slow build. Suzuki thought Miyazaki was over-exposing the Totoro. He cited E.T. to Miyazaki, saying “the alien doesn’t make an appearance until the middle of the film.” That’s technically wrong – E.T.’s first scene is full of teasing alien glimpses – but thank heaven Miyazaki didn’t know that.

There are many such gems. We read about arguments over the ending of Nausicaa (the film) and Princess Mononoke, which nearly wasn’t set in Japan, and was so expensive that some of Ghibli’s partners tried scuppering it. Elsewhere, Suzuki remembers Miyazaki scolding him for taking snaps on Ireland’s Aran Islands… then asking for the same photos. Takahata sends Suzuki on a preposterous quest to dig up a song from a lost episode of a kids’ puppet show (Hyokkori Hyoutanjima). Spirited Away, we learn, may have originated not in Shinto traditions but in a story Miyazaki heard about a Tokyo hostess club.

Fans have been making claims for years about the real meaning of Spirited Away, supposedly a prostitution allegory. Suzuki blindsides the reader by finding dubious undertones in a very different film, the sweet Whisper of the Heart, widely seen as one of Ghibli’s purest delights. On Whisper, which Miyazaki storyboarded but didn’t direct, Suzuki suggests that an avuncular-seeming character harbours not-just-fatherly feelings for the wide-eyed schoolgirl in his antique shop. Suzuki wonders who was the shopkeeper’s model, adding that Miyazaki got “terribly embarrassed” when Suzuki asked him about it. Given some of Miyazaki’s own comments in Starting Point, it’s not much of a stretch…

Fans have been making claims for years about the real meaning of Spirited Away, supposedly a prostitution allegory. Suzuki blindsides the reader by finding dubious undertones in a very different film, the sweet Whisper of the Heart, widely seen as one of Ghibli’s purest delights. On Whisper, which Miyazaki storyboarded but didn’t direct, Suzuki suggests that an avuncular-seeming character harbours not-just-fatherly feelings for the wide-eyed schoolgirl in his antique shop. Suzuki wonders who was the shopkeeper’s model, adding that Miyazaki got “terribly embarrassed” when Suzuki asked him about it. Given some of Miyazaki’s own comments in Starting Point, it’s not much of a stretch…

Beyond Miyazaki and Takahata, the most vivid supporting character is Yasuyoshi Tokuma, president of Tokuma Shoten when it owned Ghibli. Suzuki spends a few paragraphs praising the president’s decisiveness and leadership – then he lays into him. There are hilarious stories of Tokuma resenting Ghibli for beating the serious live-action films he helped produce – hands up if you’ve heard of Dreams of Russia or The Silk Road (Tonko). Even better is Suzuki’s account of how he skipped a string of numbing awards ceremony by flying away with Miyazaki on a vintage biplane, with Tokuma’s seeming approval… then getting a bollocking when he returned.

There is, of course, a question about the veracity of such stories. Suzuki almost seems to deliberately plant suspicion in the opening pages, where he quotes a book by his former boss Ogata, then describes the same quotes as “self-serving rewriting.” He also concedes, “What I write here may not be strictly accurate in terms of who did what and when”. That starts with “what I write” – this book was dictated, in interviews with Kazuo Inoue, head of sales at the publisher Iwanami Shoten.

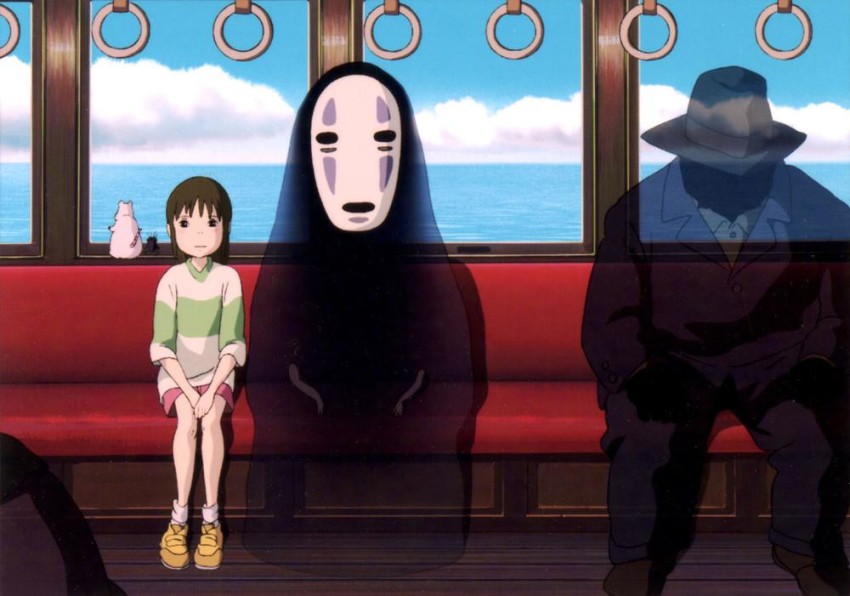

Moreover, one of Suzuki’s stories seems to directly contradict another first-hand account. At one point, Suzuki says he and Miyazaki had to decide the direction of the story in Spirited Away. According to Suzuki, it was a choice between focusing on No-face (as in the final film) or turning Spirited Away “into a story based on action and adventure.” On Suzuki’s account, Suzuki thought the adventure option “would have a longer life and be relatively uncontroversial” but that viewers might be “sucked into” the No-face story. Suzuki opted to go with No-face.

Moreover, one of Suzuki’s stories seems to directly contradict another first-hand account. At one point, Suzuki says he and Miyazaki had to decide the direction of the story in Spirited Away. According to Suzuki, it was a choice between focusing on No-face (as in the final film) or turning Spirited Away “into a story based on action and adventure.” On Suzuki’s account, Suzuki thought the adventure option “would have a longer life and be relatively uncontroversial” but that viewers might be “sucked into” the No-face story. Suzuki opted to go with No-face.

It’s a good story. But Miyazaki has told a different story more than once, including in an interview with Empire magazine. On Miyazaki’s account, No-face became central because the original story ran far too long, requiring a three-hour film. Of course, there are ways both discussions might have happened; maybe several alternate stories were being considered. However, if you’re the suspicious type, it may come down to whether you trust the artist, the ex-journalist, or neither.

Miyazaki’s is well known for starting to animate a film before he knows its ending. Suzuki, though, suggests this tendency became far more pronounced in his later films, and was a conscious policy from Mononoke onwards. This is significant, as Miyazaki’s storytelling grows considerably stranger-shaped from that point. Suzuki brings up Howl’s Moving Castle, saying its (widely criticised) ending was “hashed out” in a panic. When Howl came out, I defended its end as “pure emotional allegory,” but even I admitted, “Viewers who know only Miyazaki’s recent work may dismiss him as an undisciplined fantasist, incapable of telling a straight story.” It’s hard to imagine the late-period Miyazaki making a film with a climax as intricately ratcheted and calibrated as Shinkai’s Your Name.

Can the “wriggly, noodle-shaped” films of late Miyazaki be blamed on a growing proclivity of the director to fly blind? The evidence is strong but not conclusive. After all, Suzuki describes major story changes to Nausicaa and Totoro, two of Miyazaki’s earlier films. Miyazaki himself stresses he began the Nausicaa manga in 1982 – which would become his longest epic – without a clue where he was heading. When it comes to Miyazaki’s storytelling, the jury may still be out.

Suzuki writes substantially more on Miyazaki than Takahata. However, he beautifully pinpoints their differences; for example, Miyazaki refusing to kill a character who (Suzuki said) should die, because Miyazaki identified with her too much. This wouldn’t have impressed the director of Fireflies! Suzuki also describes Takahata’s meticulousness, both with historic accuracy and artistic technique. The “madness” of Kaguya’s production is especially well described. Suzuki wasn’t shocked that Kaguya underperformed; he was shocked by young viewers’ indifference to its artistry. “They were just following the story; they weren’t interested in the artistic expression.”

Yet Suzuki also presents his own producer role as a realist. “I don’t identify with the story heart and soul, but treat it as an object.” He went through Spirited Away with a fine toothcomb and calculated each character’s screen time, so he’d know who to highlight in the adverts. He cut the four-minute trailer for The Wind Rises as a love story, partly to pull in women viewers, and partly to placate the distributor Toho, which hated the idea of a Miyazaki war movie. Battling with Kaguya, he seriously considering sacking Takahata and replacing him.

Yet Suzuki also presents his own producer role as a realist. “I don’t identify with the story heart and soul, but treat it as an object.” He went through Spirited Away with a fine toothcomb and calculated each character’s screen time, so he’d know who to highlight in the adverts. He cut the four-minute trailer for The Wind Rises as a love story, partly to pull in women viewers, and partly to placate the distributor Toho, which hated the idea of a Miyazaki war movie. Battling with Kaguya, he seriously considering sacking Takahata and replacing him.

Yet, it’s obvious that Suzuki would never dream of treating Miyazaki and Takahata as objects themselves. He describes his reaction to clients panicking about the 10 billion yen joint cost of Wind Rises and Kaguya. “What I wanted to say in response was: Oh, just forget about all that! Miyazaki and Takahata have put their hearts and souls into these two works. Remember how much you have benefited from all that.”

The last pages include Suzuki’s notes on Mary director Hiromasa Yonebayashi. When he made Arrietty, we learn, he had to be physically sealed away from Miyazaki to stop the master interfering. Yonebayashi is “more of a stage manager than a director,” Suzuki says. Perhaps contradicting himself, he also claims Yonebayashi creates girls who “think before they act”, unlike Miyazaki heroines, which seems weirdly auteurist. The heroines of Arrietty and Marnie are indeed fascinatingly hesitant, but surely some of that comes from the writers and animators. Miyazaki himself co-wrote Arrietty, and Masashi Ando straddled both those roles on Marnie. Moreover, Yonebayashi’s new Mary film deliberately went the other way, for a strongly impulsive character.

Suzuki’s sole note on Miyazaki’s new film project, How Do You Live?, is at the start of the book, in a preface from last November. Suzuki says, “The content (of the early storyboards) was quite different from the title. It was fantasy on a grand scale… Miyazaki didn’t want to end with The Wind Rises. All said and done, his real love was adventure fantasy.”

As of last November, Suzuki confirms, Ghibli was working on two simultaneous films, How Do You Live? and a CG feature by Goro Miyazaki. A Ghibli theme park is being developed near Nagoya, Suzuki’s birthplace, with new images released just weeks ago. Its opening is scheduled for 2022, forty years after Miyazaki and Takahata worked togther on Nausicaa.

How much the sad events of April will derail these projects, especially the progress of Hayao Miyazaki’s film, is unknown. In his preface, though, Suzuki reflects, “Ghibli would continue to make films. That is its mission. That is what it does – until the very last day of its existence. I steeled myself for whatever the future might bring… Time and tide wait for no man.”

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Mixing Work with Pleasure: My Life at Studio Ghibli by Toshio Suzuki is published by Japan Library.

Leave a Reply