Books: The Ghibli No-One Talks About

December 3, 2018 · 5 comments

By Motoko Tamamuro.

I think we can see why this one wasn’t translated into English. From the moment you open Dare mo Kataranakatta Ghibli wo Kataro (Let’s Talk About the Ghibli That No One Talks About) by Ghost in the Shell director Mamoru Oshii, you are assaulted by a machine-gun salvo of incendiary language. Hayao Miyazaki “cannot direct” – he is “less than second-rate as a director.” “There is no coherent clear story”. “Mood” and “ideas” dictate his films and “there is no logic”. Meanwhile, Isao Takahata turned into a “shit intellect” who created “propaganda films.”

I think we can see why this one wasn’t translated into English. From the moment you open Dare mo Kataranakatta Ghibli wo Kataro (Let’s Talk About the Ghibli That No One Talks About) by Ghost in the Shell director Mamoru Oshii, you are assaulted by a machine-gun salvo of incendiary language. Hayao Miyazaki “cannot direct” – he is “less than second-rate as a director.” “There is no coherent clear story”. “Mood” and “ideas” dictate his films and “there is no logic”. Meanwhile, Isao Takahata turned into a “shit intellect” who created “propaganda films.”

The book comprises four chapters written in an interview format. The first chapter is devoted to Miyazaki, and Oshii shreds one title after another from Nausicaä of Valley of the Wind (1984) to The Wind Rises (2013). The victim of the second chapter is Takahata from Grave of the Fireflies (1988) to The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013). He talks about the other directors in the third chapter, and summarises and talks about post-Ghibli in the final chapter.

The book comprises four chapters written in an interview format. The first chapter is devoted to Miyazaki, and Oshii shreds one title after another from Nausicaä of Valley of the Wind (1984) to The Wind Rises (2013). The victim of the second chapter is Takahata from Grave of the Fireflies (1988) to The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013). He talks about the other directors in the third chapter, and summarises and talks about post-Ghibli in the final chapter.

Being a frequent visitor to the Ghibli studio and Miyazaki’s second home, and having debated and argued about creative approaches with the studio’s founders, Oshii has unique observations and opinions about the directors and their individual films, but his insights into the producer Toshio Suzuki’s involvement is even more fascinating, shedding light into the power balance within the studio. Ghibli was created “to make entertaining cartoons” following the success of Nausicaä. However, by My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and its co-release Grave of the Fireflies, it became apparent that the two directors had too many issues that they wanted to discuss for children’s films – Miyazaki’s “farming village and forest worship” in Totoro and Takahata depicting “his view of life (or sex) and death” in Fireflies. Until then, Takahata worked as a producer for Miyazaki, but thereafter, Suzuki came to the fore to sell the two “artists”. Suzuki had the ability to mobilise anime otaku, but he started to ignore them and instead concentrated on the general public, because Studio Ghibli could not survive by just pleasing fans.

For Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), Suzuki questioned Miyazaki’s fixation on his own stories, so Oshii believes the producer chose and presented someone else’s intellectual property to the animator-turned-director. “This is my guess – but I’m sure I’m not wrong – why did he choose the story of that girl? Probably it was Toshio Suzuki who chose it. Back then, he was crazy about his daughter. He was obsessed with his daughter for a long while, but I bet that time was the peak. So, he wanted to do Kiki’s story about a girl leaving the nest. As a father of a daughter. There is no problem there. But, the heroine was slightly different from the type Miya-san (Miyazaki’s nickname) was after.” Miyazaki loves perfect girls. Miyazaki’s heroine would never go to the loo like Kiki did in the film, which apparently shocked those who knew Miyazaki. Why did he do that, then? Oshii believes Suzuki kept whispering into Miyazaki’s ears, “Miya-san, the beautiful girls you have depicted are not good. You should make her a character that real girls can empathise with.” According to Oshii, Suzuki is a Hollywood type producer who wants to control the staff to express himself using “intimidation” and “pacification”. But ‘an imperfect youth moving elsewhere and turn good’ soon became a pattern for Ghibli films to come. Oshii thinks Suzuki is behind it, because “I cannot find a connection with the essence of Miya-san.”

After grudgingly creating Kiki, Miyazaki was given a treat – allowed to indulge himself in Porco Rosso (1992). For Princess Mononoke (1997), Miyazaki threw in everything he studied and was interested in, including Japanese culture, nature, human, and civilisation. Suzuki pushed Miyazaki’s artistic and intellectual sides even further forward. But the film also has the notorious scenes with chopped head and arms flying around. Although Miyazaki likes military history and had a tendency to include cruel scenes in his films, Oshii believes that was a sign of Miyazaki becoming “unstoppable”. As a result, Suzuki had to do anything and everything to promote the film, including an all-star cast, whom Suzuki lined up for the premiere. For the production of Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), digital technology was used, so Miyazaki wanted to show what he could do with traditional animation technique in Ponyo (2008). “Hayao strikes back.” “I think Toshi-chan (Suzuki’s nickname) tried to suppress Miya-san going out of control up until certain point, but at around Howl, he completely gave up. After all, films with full-throttle fantasy did not drop the sales figures, so Toshi-chan had to throw in the towel. And that gave Miya-san the impression that he could do whatever he liked.” Interestingly, Oshii ends up arguing that the more successful Ghibli became, the less influential Suzuki became within the studio.

After grudgingly creating Kiki, Miyazaki was given a treat – allowed to indulge himself in Porco Rosso (1992). For Princess Mononoke (1997), Miyazaki threw in everything he studied and was interested in, including Japanese culture, nature, human, and civilisation. Suzuki pushed Miyazaki’s artistic and intellectual sides even further forward. But the film also has the notorious scenes with chopped head and arms flying around. Although Miyazaki likes military history and had a tendency to include cruel scenes in his films, Oshii believes that was a sign of Miyazaki becoming “unstoppable”. As a result, Suzuki had to do anything and everything to promote the film, including an all-star cast, whom Suzuki lined up for the premiere. For the production of Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), digital technology was used, so Miyazaki wanted to show what he could do with traditional animation technique in Ponyo (2008). “Hayao strikes back.” “I think Toshi-chan (Suzuki’s nickname) tried to suppress Miya-san going out of control up until certain point, but at around Howl, he completely gave up. After all, films with full-throttle fantasy did not drop the sales figures, so Toshi-chan had to throw in the towel. And that gave Miya-san the impression that he could do whatever he liked.” Interestingly, Oshii ends up arguing that the more successful Ghibli became, the less influential Suzuki became within the studio.

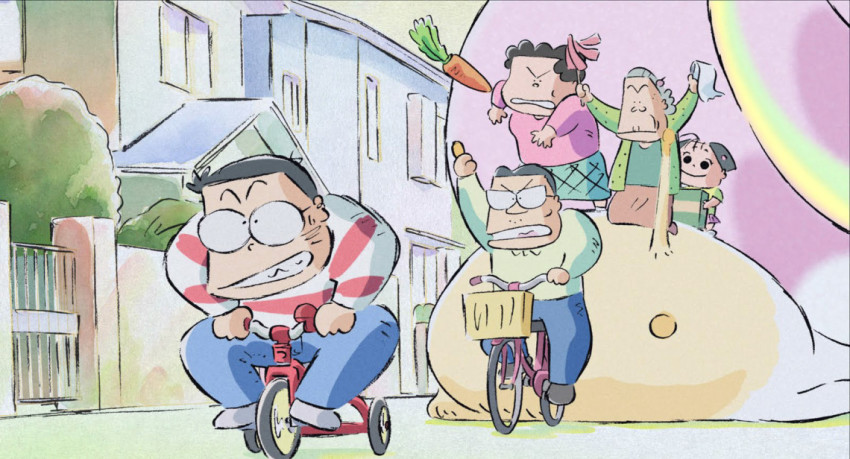

As for Takahata, his films turned “Marxist” after Only Yesterday (1991), so Suzuki must have asked him to create another Chie the Brat (1981), one of his best works, with My Neighbours the Yamadas (1999). But it flopped. Also, Takahata put the animators through a hard time experimenting with different expressions, only to find out the techniques born out of this film are something can be done easily using digital. The relationship between Takahata and Ghibli, claims Oshii, “went bust”. Even Miyazaki got angry enough to say: “We will never let Paku-san (Takahata’s nickname) direct again”. Although, he was eventually allowed to create big-budgeted The Tale of Princess Kaguya thanks to Ghibli’s patron, Seiichiro Ujiie.

Of course, the biggest question was why people of all ages flocked to see Ghibli films. Princess Mononoke’s box office revenue was 19.3 billion yen, Spirited Away 30.8 billion yen, and Howl’s Moving Castle 19.6 billion yen. As mentioned above, Suzuki painted the two as “artists”, but according to Oshii, the success of Princess Mononoke made Miyazaki a “great master”. Japanese people never question great masters, and started to go to see their works believing they were worth it. That also allowed Ghibli to flourish free of negative press. But Oshii thinks there was a more sinister reason.

Any film by any director goes through strict scrutiny – some people love it and others hate it. But why were Studio Ghibli’s works always so highly praised in Japan? Oshii argues that it was because Toshio Suzuki, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata ran “a reign of terror” with Suzuki being “a chief of its secret police” who is a master of “intimidation”, creating an “inner circle” within Ghibli and keeping everything among themselves. However, rather than Suzuki going around and crushing negative press (which is totally plausible, but in reality, is impossible to do), the media themselves curtailed any criticism. Why? Because they had nothing to gain from denigrating Ghibli.

But, there is a fundamental reason why people love Ghibli. Oshii quotes someone saying, “Funny enough, when you are watching Ghibli films, you can feel that you are a good person”. Although Oshii dismisses Miyazaki for lacking the talent to build structure in a film, to create a world, or make a story, he admits the director has full of talent to “show beautiful things momentarily like a magic”. His fantasy moves people. Miyazaki’s aim was to show “the pleasure of living” by “giving everyone a dream”. He is “peerless” as an animator and has a great ability to depict nature and everyday behaviour. He is capable to emotionally move people by animating pictures “in the way nobody else can”. Oshii believes that Miyazaki’s films will survive and they will keep children happy generation after generation.

As for Takahata, Oshii grudgingly admits he was a top director. He was frustrated by Takahata’s Ghibli works after Fireflies, but he declares that there is no one in the anime industry who was not influenced by him. At the time of Anne of Green Gables (1979) and Chie the Brat the director was at the peak of his career. All the younger generation anime directors including Oshii studied them closely and learnt a lot from them.

This was a fun read and despite Oshii’s explosive comments, somehow I could feel the author’s love and admiration towards the anime giants seeping through. In that sense, it is not a simple “dishing the dirt” book, and after embracing the creators’ imperfections, this book makes you want to watch Ghibli films again.

Let’s Talk About the Ghibli that No-one Talks About, by Mamoru Oshii, is published in Japanese by Tokyo News Books.

anime, books, cinema, Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, Japan, Mamoru Oshii, Motoko Tamamuro, Studio Ghibli

JD

December 5, 2018 4:54 pm

This all sounds a bit like a case of sour-grapes on the part of Oshii. i get the impression, is that he's basically s**t-stirring, and desperate for either some attention, or for a similar kind of success (financial or ratings) that Studio Ghibli have had. I'm all for critical discussions and examining whether success is truly warranted, but simply writing that you don't believe they deserve success, is really poor, and I pity Oshii-san.

Jules

July 2, 2019 5:08 am

He's right, though.

Matheus Bezerra de Lima

October 11, 2021 5:04 pm

Could you explain? I think his criticisms came across as destructive rather than constructive, and also way too nasty in tone.

Carl

December 14, 2018 12:40 am

The mutual respect and admiration my favorite anime directors show for each other is always heartwarming to see ^_^ I'm sure the question that's going to occur to a lot of people is, how does Oshii view the differences between his own professional and creative relationship with Suzuki, versus Miyazaki and Takahata's relationship with him? After all, Toshio Suzuki (and Ghibli) was the co-producer of Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence. In his recent biography, Yoshitaka Amano recalls Suzuki as a co-producer on The Angel's Egg as well. You wouldn't call either of those films watered-down Oshii.

Francesco

January 17, 2019 1:53 am

Oshii the director of Angels Egg and Ghost in the Shell 2 thinks Miyazaki makes movies where ‘There is no coherent clear story”. Either he is projecting or that was ment as a compliment.