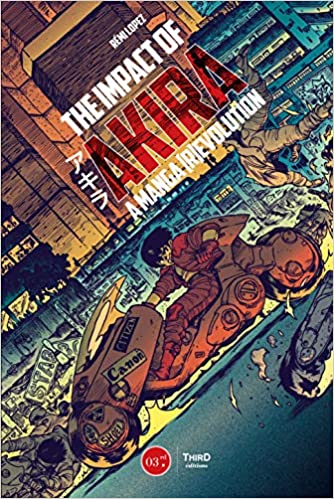

Books: The Impact of Akira

February 15, 2021 · 2 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

If you were asked which singer comes to mind in connection with Akira, most readers would think of Kanye West cosplaying Tetsuo in his pants in the “Stronger” video. A few of you might remember Michael and Janet Jackson’s video for “Scream,” which samples Akira in its last moments. But in his new book The Impact of Akira, author Rémi Lopez reveals that when Otomo was writing his manga, the artist had a British singer in mind as a model for his truculent biker Kaneda. Otomo was thinking of… Sting.

Sting?

Well, that’s what Otomo said in a lecture in Angouleme in 2016. Specifically, Otomo was thinking of Sting’s crimson outfit in the video for the 1983 song “Synchronicity II.” How strange that Kaneda, the youthful face of Cool Japan to the world, could be linked to a song with the lyric, “We have to shout above the din of our Rice Krispies!” Surely some Youtuber could do a “live-action Akira”mock trailer using shots of Sting from his days of 1980s thesp glory in Dune and The Bride.

(And yes, before anyone points it out, the song was released in 1983, whereas the Akira manga debuted in Japan in December 1982. However, the manga was nearly all monochrome in its Japanese printing; Kaneda’s red-suited glory arrived in later covers and in the 1988 movie.)

The Impact of Akira is an informative if uneven book. Its early pages are a mine of great information like the Sting bit – okay, so few revelations are quite as good as that. Later on, though, the book threatens to lose sight of Akira in a jungle of context denser than Neo-Tokyo.

The first seventy pages are best, a straight account of Akira’s creation within Otomo’s career, which Lopez chronicles enjoyably. Although the manga Akira was published in Young Magazine, Otomo had his first break as a 19-year-old in Manga Action, which also ran Lupin III and Lone Wolf and Cub. Otomo’s own early strips in the 1970s included reworkings of Western stories – for example, his “Shinyu”was based on a doppelganger story by Edgar Allen Poe, “William Wilson.”

He then moved onto original pieces, often with strange characters and dark situations. “Nothing Will Be as it Was,” for example, deals with corpse disposal; a refrigerator is involved – this was pre-Jeffrey Dahmer. By the end of the 1970s, Otomo was moving into SF, both with short pieces and his better-known longer strips, Fireball in 1979 and Domu in the early 1980s. The latter was the story of a monstrous old man and a calm little girl, both possessing psychic powers and a tendency to blow stuff up. Akira’s seeds are obvious. Lopez mentions Domu was the first manga to win the Nihon SF Taisho Grand Prize, which caused some grumbling among fans who disliked the medium. However, Domu was defended by a previous prize-winner, Sakyo Komatsu, the author of Japan Sinks.

Moving to Akira itself, Lopez points up its debts to past comics. An obvious manga referent was the mecha classic Tetsujin-28 by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, with its hero Kaneda and its secret weapon designated #28. But Lopez also points up the impact of Blade Runner, which itself drew on the urban gigantism of France’s The Long Tomorrow, a 1976 French strip drawn by Moebius. Meanwhile, Kaneda’s motorbike was inspired by Peter Fonda’s steed in Easy Rider (the one that explodes at the end of the film) and by the videogame bikes in Disney’s Tron – remember those light trails they leave. As for the end of the strip, we learn it was hammered out in a Tokyo Chinese restaurant, between Otomo and a drunken friend who’d come visiting – Alejandro Jodorowsky, director of El Topo.

Lopez also goes through the circumstances in which Akira arrived in America, driven by the market assumptions of the time. Otomo didn’t want the strip perceived as “something bizarre from Japan”; consequently, he not only approved its left-to-right flipping but adjusted the flipped pictures himself. He also wanted Akira in colour; to help the colourist, Steve Oliff, Otomo sent him slides from the anime film, then in production. This localised version was published by the Marvel imprint Epic Comics; many British readers read it in Manga Mania magazine, where it was still flipped but in black and white.

As for the film, we learn that when Otomo saw Akira at the premiere, he became convinced it would flop. “I felt,” he said, “that the quality plummeted as the story developed.” Instead, of course, it made his name around the globe, although as Lopez reminds us, the artist has never hit such highs again. Some fans love his blockbuster follow-up, Steamboy, but it failed to recoup its massive budget. Since then, Otomo’s projects have grown increasingly intermittent, though in 2019 it was announced he’ll direct a new film, Orbital Era (teaser) while there’ll also be a new Akira anime in some form.

This part of the book is tight and engaging. Later the discussion spreads out, not always to its benefit. Lopez opts not to do a scene-by-scene or act-by-act commentary on Akira. Rather, he handles it by topic, bringing up may of the obvious elements of Akira and discussing each of them in turn. So, there are chapters on the legacy of the A-Bomb; Japan’s biker street gangs and student insurrections; Japan’s clan mentality (tied into Tetsuo’s insubordination towards Kaneda); body horror and cyberpunk; visions of post-disaster worlds; and Akira’s take on the transcendental.

As I said above, my main problem with this part of the book is that it often seemed to lose sight of Akira itself. All the subjects are plainly relevant, and readers interested in these angles will find useful material, but the rambling is infuriating.

To take the A-Bomb section, Lopez offers some great insights, such as comparing the portrayals of Akira’s politicians to those in a vintage Tezuka strip, Next World (1951), about an island mutated by bombing. He also suggests vivid parallels between Akira and Barefoot Gen, in their iconography of boys standing defiantly atop destroyed worlds. Akira himself is compared to Japan’s repressed wartime history, buried under tons of concrete and sealed doors, in a base that happens to have two exits – one to a spanking new Olympic stadium, and the other to a huge bomb crater.

All of that is great. But the chapter still feels like a very long wade, also bringing in Godzilla, vintage tokusatsu shows, Yamato, Ideon, Nausicaa… You get the idea. The same tends to apply to the later chapters. I enjoyed some of these rambles; for example, learning more about the Japanese biker gangs or bosozoku, a subculture at its apogee when Akira began – there were more than forty thousand Japanese bikers in 1982, and their presence was a substantial contribution to the forgotten early OAV genre of “bike-mono.” The bosokozu used right-wing slogans, but they may have been more inspired by the “Chicken Run” scene of Rebel Without a Cause than by the seppuku of Yukio Mishima.

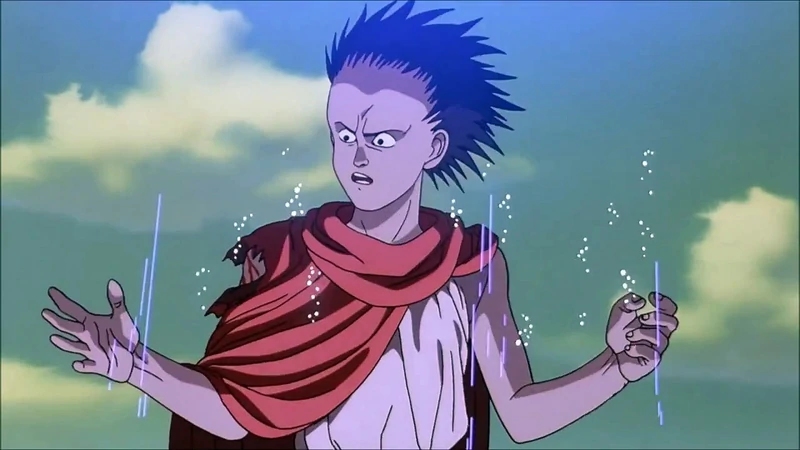

Still, Lopez’s wanderings can be exasperating, as when his discussion on cyberpunk and body horror drifts into talk about Dragon Ball Z, the Guinea Pig horror films and the octopuses dreamed up by a horny Hokusai (NSFW). But every few pages, there’s a really interesting parallel to stay with you. For example, near the book’s end, Lopez reflects on Kaneda’s final deeds in the strip. They turn on the boy’s refusal to give up what he’s experienced in the story, however horrible. Lopez compares this to a Japanese novel, Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids by Kenzaburo Oe, written back in 1958.

Of course, you can end up arguing with Lopez. For example, he classes Akira as a cyberpunk story, which will put your back up if you think a criterion of the genre is that it deals with cyberspace, like Neuromancer. My own feeling is the “cyberpunk” that Japanese film fans talk about is different from the kind that Neuromancer fans would recognise, despite overlaps between them. Then again, I also think Akira is nearer to Gibson’s cyberpunk than Ghost in the Shell is, because Ghost takes the angle of law enforcers while Akira’s heroes are, well, punks.

The book has a few gaffes. On the second page, Lopez suggests the very first Japanese animated feature film was Hakujaden in 1958. Hopefully, readers of this blog can put him right on that front. Lopez also suggests that today’s stories of paranormally-powered teens in sinister experiments derive from Akira. I think Marvel Comics might have something to say about that; and as a child, I encountered that kind of story in a 1978 Disney film, Return from Witch Mountain.

Also, one omission; in Lopez’s account of Otomo’s post-Akira work, I was surprised he didn’t mention the artist’s designs for the 2006 video series Freedom, which strove to recall Akira as much as possible. (Here’s the tie-in Hikaru Utada music video.) But there’s a far more amazing omission. Akira, you may recall, ends up with a character swelling into a bloated mass of flesh. Lopez discusses this image from several angles, without ever focusing on the most obvious reading in a film about adolescent boys. Again, Marvel Comics might have something to say on the subject…

The Impact of Akira title is also somewhat misleading. Lopez isn’t very interested in the response to Akira, both in Japan and worldwide. In particular, he has nothing to say on how it practically created the anime industry in Britain, defining the image and marketability of “manga movies” for many years. For what it’s worth, I wrote an article from this angle several years ago, also called “The Impact of Akira.”

But then, Lopez suggests Akira may be unrepeatable anyway. At least in the manga industry, he argues “publishers now have much more control over the artistic process, and the market has transformed into one of mass production.” It’s a similar line to the one Peter Biskind takes on Hollywood. Maybe Lopez is right, though I’ve argued that there are many parallels between Akira and a current manga juggernaut, Attack on Titan. Both stories are motored by the rage of teen boys, as well as by provocative geopolitics. I used to be sceptical of political readings of Attack on Titan, but anyone who’s kept up with the later chapters knows it’s all geopolitics now.

And if we’re being mischievous, why not point out the ways Akira anticipates a different pop-culture giant? I’m thinking of another story about two very close characters, one of them bursting with uncontrollable powers, whose only escape may be to build a new world. And if you can’t guess what I’m thinking of… just let it go.

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. The Impact of Akira is published in English by Third Editions.

Andrew Niven

June 22, 2021 6:55 am

The final tease reminds me that in a way one can say Akira exists as a precursor or early example of the "sekai-kei" genre, since the cryptic description you provided kind of fits as the quintessential core of that kind of story. That being said, maybe you're hinting at Neon Genesis Evangelion? With Shinji in Tetsuo's role and Asuka in Kaneda's? (very broadly speaking of course).

Andrew Osmond

June 22, 2021 9:29 am

Thanks very much for the comment! Actually, the clue was in my 'let it go" comment - I was thinking that Elsa in the Disney film Frozen had more than a few parallels with Tetsuo.