Books: Your Name

November 4, 2017 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

In the afterword to his Your Name novel, now available in English from Yen On in hardcover and on Kindle, Makoto Shinkai says the book isn’t just an adaptation of his film. Rather, it was part of the film’s production process. The novel was written while Your Name was being animated, with Shinkai composing it at home and in the production studio, “about half in each location”.

In the afterword to his Your Name novel, now available in English from Yen On in hardcover and on Kindle, Makoto Shinkai says the book isn’t just an adaptation of his film. Rather, it was part of the film’s production process. The novel was written while Your Name was being animated, with Shinkai composing it at home and in the production studio, “about half in each location”.

In particular, Shinkai says that writing the book let him rethink the film’s characters, which influenced the recording sessions for the anime when the voices were added. “The book really helped me direct the characters, because I knew more about the characters,” Shinkai confirmed when he talked about Your Name in London.

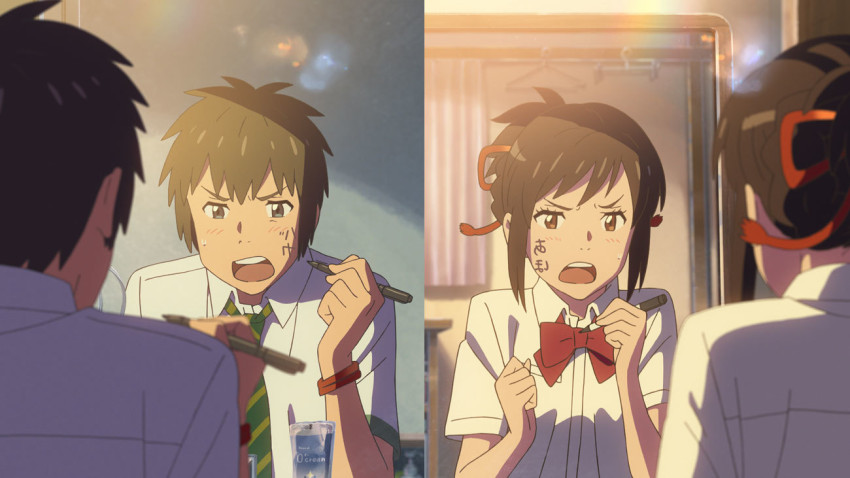

As Shinkai acknowledges, there are no substantial story differences between film and book, and yet there’s an important shift of emphasis. The novel is written entirely from the first-person viewpoints of the main characters, Mitsuha (the girl) and Taki (the boy). Of course, their viewpoints were crucial in the film, too. Think how nearly all Your Name’s early scenes have Mitsuha at their centre, in her body or Taki’s, and how this makes the twist more shocking. But Shinkai felt the yearnings of Mitsuha and Taki needed to “be related with an immediacy that differed from the glamour of the movie, and I think that’s why I wrote this book.”

It’s a tall order. The anime’s glamour is overwhelming, and of course most readers will have it playing in their heads as they read the book. And yet Shinkai’s right; without the screen dazzle, the characters’ emotions are truly foregrounded. That’s most obvious in the story’s desperate moments, but it shows in other places too.

The girl’s voice – its echoes – still whispers in my ears… Still, it was just a dream. It doesn’t mean anything. By the time I think about it, I can’t even remember her face. The echoes in my ears are already gone too.

Even so.

Even so, my pulse is still racing abnormally fast. My chest is weirdly heavy. I’m sweaty all over. For the moment, I draw a deep breath.

Your Name’s prose is far less outstanding than the anime’s visuals, which often conjured a sense of poetry. When I watch the climactic image of the meteor crashing down to earth, to a shockingly joyous song by Radwimps, I wonder how Ray Bradbury, master of the lyrical apocalypse, would have rendered it in prose. Screen motifs like the paired flying birds, or the revelation in the cave through gorgeous fluid metaphors, don’t have the same force on the page. But Shinkai’s book is still a good read, and far better than another recent adaptation, Mamoru Hosoda’s book of The Boy and the Beast (reviewed here).

Your Name’s prose is far less outstanding than the anime’s visuals, which often conjured a sense of poetry. When I watch the climactic image of the meteor crashing down to earth, to a shockingly joyous song by Radwimps, I wonder how Ray Bradbury, master of the lyrical apocalypse, would have rendered it in prose. Screen motifs like the paired flying birds, or the revelation in the cave through gorgeous fluid metaphors, don’t have the same force on the page. But Shinkai’s book is still a good read, and far better than another recent adaptation, Mamoru Hosoda’s book of The Boy and the Beast (reviewed here).

One thing that sank Hosoda’s book was the switching between different narrators, which was dreadfully clumsy and unnecessary. Your Name’s first-person swaps between its two protagonists are much more elegant, sometimes recalling a novel with a not-dissimilar subject, Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife. But Your Name has an extra thematic justification. More than the film, the book stresses how Mitsuha and Taki have linked memories and experiences, their minds spilling into each other.

Mitsuha’s soul must be in my body, right now. After all, my heart’s here, in hers. But… Without even asking, I can tell who Mitsuha likes and who she’s not comfortable around. When I see her grandma, memories I shouldn’t even have rise hazily in my mind, like a projector with broken focus. Body and memories and emotions are bound together inseparably.

In particular, the book clears up a confusion on screen. Late in the film, one sequence cuts back and forth between Taki “as” Mitsuha, bicycling in frantic search of his other half, and a flashback of Mitsuha going to Tokyo and finding a younger Taki. The idea, as the book confirms, is that Taki and Mitsuha have converged so closely that Mitsuha’s memories are leaking into Taki, letting him relive the meeting from her viewpoint.

It’s also clarified that Mitsuha doesn’t despise the countryside as much as her vocal protests suggest, which rings true; don’t expect nuance from a stroppy teen! Rather, it’s Mitsuha’s ceremonial duties, and specifically the way she must dribble rice in public to create “mouth-brewed sake”, that really gets to her. A nice touch is that Mitsuha’s little sister, who also performs the ritual, has no such problems. The agonies of being a teenager…

Mentally sniffling, I pick up another pinch of rice and put it in my mouth like a trooper. Then I chew again… We have to do this over and over until the tiny boxes are full. I spit saliva and rice again. Inside I’m crying my eyes out.

Another suggestion that’s more amplified in the book is that the characters’ sexual orientations are swayed by whose body they’re in. Mitsuha-as-Taki certainly seems taken with the lovely senpai Okudera (who’s Taki’s own secret crush). Later, Taki-as-Mitsuha cozies up to Tesshi, the country boy who secretly crushes on Mitsuha, in a manner suggesting more than horseplay. I press my body against him some more. Here you go – have a freebie! (He) resists, big body squirming. He’s a guy for sure… Well, so am I.

Another suggestion that’s more amplified in the book is that the characters’ sexual orientations are swayed by whose body they’re in. Mitsuha-as-Taki certainly seems taken with the lovely senpai Okudera (who’s Taki’s own secret crush). Later, Taki-as-Mitsuha cozies up to Tesshi, the country boy who secretly crushes on Mitsuha, in a manner suggesting more than horseplay. I press my body against him some more. Here you go – have a freebie! (He) resists, big body squirming. He’s a guy for sure… Well, so am I.

It makes you wonder how Mitsuha and Taki would have interacted if they’d met at twilight in each other’s bodies… That’s an “alternate” scene it would have been interesting to read. The book passes up other chances to widen the story, such as showing more of Taki being “swapped” into Mitsuha’s life, or showing the last face-off between Mitsuha and her dad as the comet descends. Indeed, more scenes with Mitsuha’s dad would have been welcome. For instance, does he spend the rest of his life being chased by conspiracy theorists?

Misc observations:

The joke about Mitsuha-as-Taki getting muddled about Japanese pronouns is represented in the translation by Mitsuha trying the expressions, “Excuse me”, “Pardon me”, “Sorry,” and “Whatever.” It’s not very convincing, but it could have been worse.

It’s suggested that the braided cords and the gestures of Itomori’s Shinto dance are both ancient warnings of previous comets, which fell on the area twice since Japan was settled. As such, these warnings are comparable to Japan’s ancient tsunami markers. Like the film, the book doesn’t overtly reference the 2011 tsunami disaster but Shinkai has been open about how it motivated him to make Your Name.

Surprisingly, the “senpai” Okudera is more vulnerable in the book than in the animation – I preferred the film version. The book also points up a visual detail about her status at the end that some viewers might have missed.

Country dialect is mostly rendered by the Itomori characters dropping their g’s (comin’ instead of coming, for example). This seems to have really annoyed one Amazon reviewer, but I found it quite acceptable.

Tessie reads MU magazine, a real Japanese magazine about strange phenomena and conspiracies, like Britain’s Fortean Times.

In his afterword, Shinkai says “the book was greatly influenced by the world of RADWIMPS’s lyrics.” Indeed, the text neatly weaves in references to RADWIMPS’s music, especially at the beginning and end. Just a little longer…

The book also has a second afterword, by producer Genki Kawamura, whom Shinkai credits with shaping the film through his “brisk and decisive” suggestions. Kawamura offers his own take on Your Name, starting from the premise that forgetting can be worse than dying.

Writing before the film’s release, Kawamura concludes, “The world is about to meet Makoto Shinkai’s ultimate masterpiece.” For us looking back… Well, for once, it doesn’t just look like hype.

Your Name is published in English by Yen On.

Leave a Reply