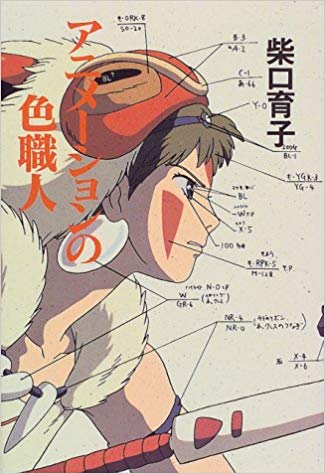

Books: Living Colour

January 14, 2019 · 0 comments

By Motoko Tamamuro.

Yasuko Shibaguchi’s book, The Colour Artisan of Animation, is one of the (currently) untranslated gems of anime history, an account of the career of Michiyo Yasuda (1939-2016), described by Hayao Miyazaki as “three times sharper and more particular than me,” and a mainstay of Studio Ghibli. This biography throws light on the overlooked world of animation finishing, a real backstage job, usually undertaken by a group of girls in a factory-like environment, a vital part of the animation process, but often overlooked by observers focussing on the more glamorous work of animation itself. Yasuda was a major influence in the elevation of finish animators in industry understanding, and without her input, the fantastic worlds of Ghibli’s films would have been very difficult. It can hence be read as the biography of a particular Japanese woman, but also as a history of women, and of animation.

Yasuko Shibaguchi’s book, The Colour Artisan of Animation, is one of the (currently) untranslated gems of anime history, an account of the career of Michiyo Yasuda (1939-2016), described by Hayao Miyazaki as “three times sharper and more particular than me,” and a mainstay of Studio Ghibli. This biography throws light on the overlooked world of animation finishing, a real backstage job, usually undertaken by a group of girls in a factory-like environment, a vital part of the animation process, but often overlooked by observers focussing on the more glamorous work of animation itself. Yasuda was a major influence in the elevation of finish animators in industry understanding, and without her input, the fantastic worlds of Ghibli’s films would have been very difficult. It can hence be read as the biography of a particular Japanese woman, but also as a history of women, and of animation.  Yasuda has collaborated with Japan’s greatest directors since the 1960s. In Takahata’s words, she had “an outstanding sense and technique. I love her craftsmanship. Not only is she capable of her job, but she can also see the whole picture, so I want her to be in the centre of the team when I make a film. Being comrades since our Toei Doga era, we have inspired one another to make a movie together.” She was lauded for her colour design, marshalling 546 colours on Princess Mononoke, of which 30-40 were used for the character of Prince Ashitaka alone, reflecting his personality and culture, as well as subtle nuances in light and shadow.

Yasuda has collaborated with Japan’s greatest directors since the 1960s. In Takahata’s words, she had “an outstanding sense and technique. I love her craftsmanship. Not only is she capable of her job, but she can also see the whole picture, so I want her to be in the centre of the team when I make a film. Being comrades since our Toei Doga era, we have inspired one another to make a movie together.” She was lauded for her colour design, marshalling 546 colours on Princess Mononoke, of which 30-40 were used for the character of Prince Ashitaka alone, reflecting his personality and culture, as well as subtle nuances in light and shadow.

She did not go into animation as an artist. Graduating from high school in 1958, she started working as a finisher at Toei because “it sounded interesting, different from the other jobs” – the other jobs being secretarial positions or working as a shop-girl. “I didn’t even know what animation was.”

Yasuda found herself painting cels and tracing in-between lines for commercials. It had only been five years since Japan got its first commercial broadcaster, and “everything was fresh and interesting.” In 1963, she claims that a “recession” led to the decline of TV commercials – in fact, advertising was doing fine, but as noted in Jonathan Clements’s Anime: A History, “advertising and sponsorship… were diluted across multiple channels and properties, and would never repeat the rapid revenue rise of the years 1958-63.” Facing fiercer competition from cheaper start-ups like Mushi Pro, Toei shut down its dedicated commercial finishing section, and Yasuda found herself shunted into work on animated cartoons.

Wolf Boy Ken, Toei’s response to Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy, went on the air in November 1963. Out of her comfort zone in a new environment, Yasuda joined the trade union, which was where she met Takahata and Miyazaki. But she did not only devote herself to the work and the trade union activities like them. After negotiations with the trade union that ran through the night, the self-proclaimed ‘party animal’ spent the next evening dancing at a newly-opened disco.

The Toei company was learning the hard way of the boom-and-bust workloads of the animation industry – sometimes requiring just two guys with a pencil and paper, sometimes 200 animators working through the night. Yasuda was drafted back into commercials, and then shoved out again, accepting her fate with willingness after hearing that Takahata was planning something very different with his debut feature project, Little Norse Prince. Yasuda willingly volunteered for Takahata’s experimental film, which notoriously ran over-budget and under-performed at cinemas. She left Toei in 1968, the year of Little Norse Prince’s dismal box-office flop, but was lured back into animation several years later after seeing Takahata’s post-Toei project, Heidi: Girl of the Alps.

Working at Zuiyo (later Nippon Animation), Yasuda was the newly minted “colour designer”, to whom choices of minor colours, formerly the responsibility of the art director, was now delegated. This soon threw her into contact with Takahata’s famously picky protégé Hayao Miyazaki, with whom she found herself collaborating on ever more complex colour details on 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother. Miyazaki recalled: “Because basically I did not like this piece, I decided to make experimental colour combinations and screen compositions. How we could make food look delicious and how to express the sparkling of a glass surface, how we could make the picture stand out by depicting the details of things and designing colours… It was [Yasuda] whom I experimented with about these things.” They also observed how light changes colours. “With this piece,” commented Yasuda, “I learned the basic of a colour scheme and I feel this was the start of my colour design career.”

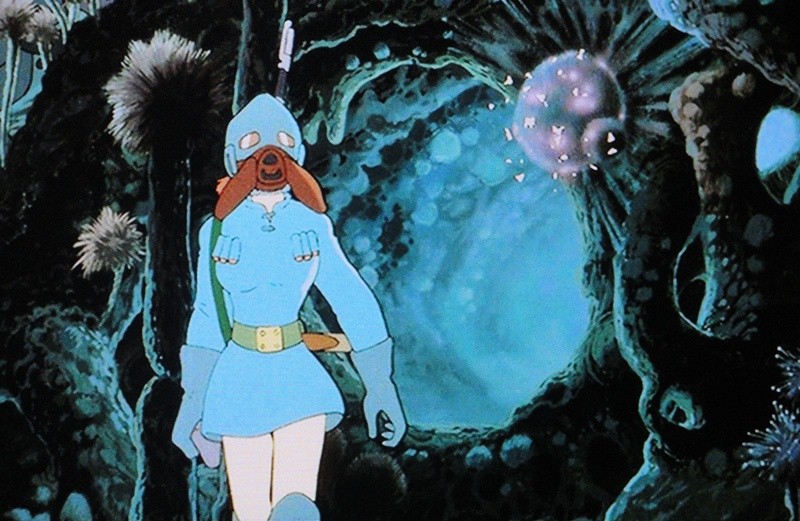

In 1979 Miyazaki left Nihon Animation and Takahata followed him in 1981. Yasuda stayed back, but got increasingly frustrated and realised that anime need a director with a clear vision. In 1983, Takahata called her to invite her to jump ship to work on a film he was producing and Miyzaki was directing: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, for which she came up with a palette of 262 colours, compared to the 170 then in use on television. After moonlighting on Nausicaä, she quite Nippon Animation for good when Takahata and Miyazaki set up their own studio, becoming Ghibli’s chief of finishing, with work spanning colour design, colour specification, supervising tracing and painting, outsourcing, to the finishing check.

In 1979 Miyazaki left Nihon Animation and Takahata followed him in 1981. Yasuda stayed back, but got increasingly frustrated and realised that anime need a director with a clear vision. In 1983, Takahata called her to invite her to jump ship to work on a film he was producing and Miyzaki was directing: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, for which she came up with a palette of 262 colours, compared to the 170 then in use on television. After moonlighting on Nausicaä, she quite Nippon Animation for good when Takahata and Miyazaki set up their own studio, becoming Ghibli’s chief of finishing, with work spanning colour design, colour specification, supervising tracing and painting, outsourcing, to the finishing check.

When it was decided that Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbour Totoro would be released on a double bill, Ghibli was obliged to split its animators into separate teams. Yasuda became the subject of a tug-of-war between Takahata and Miyazaki, leading to an uneasy compromise in which she worked officially on Fireflies, but also did colour design and supervision on Totoro. The films became an important landmark in her career, as they led to her importuning STAC, the anime paint manufacturer, to develop new colours for her. The company initially refused, arguing that there was little commercial potential in developing bespoke shades and hues, but somehow she charmed them into playing along.

Her people skills were also crucial in outsourcing staff. When the production of Fireflies was delayed, she rang around people she used to work with, people she taught and everyone she could think of, and they rushed to help her. Still, they ran out of time and when the film was released, there were some shots that were still not finished. Even after the film reached cinemas, they kept painting, sneaking finished scenes one-by-one back into the prints in cinemas. As for the paints, she used 304 colours for Fireflies and about 80% of them were new colours made specifically for the film. For Totoro, about half of the 303 colours were new colours.

Yasuda sensed oncoming change on Pompoko (1994), for which she was still finishing by hand, but which other departments were starting to use computers. Given a chance to play around with digital animation after Pompoko was completed, Yasuda realised that technology would have substantially reduced her workload, but also that it would lead to lay-offs. Her biography’s 1990s chapters hence detail her growing apprehension about the oncoming digital disruption. Her main contact at STAC retired, and with neither STAC nor their rivals Taiyo Shikisai giving her the paint she needs, she guiltily approached the Canadian company Chromacolour. Although she complained about their materials, she used 91 Canadian colours in Princess Mononoke, while fretting all the while that every overseas contract was another nail in the coffin of domestic industries.

Yasuda sensed oncoming change on Pompoko (1994), for which she was still finishing by hand, but which other departments were starting to use computers. Given a chance to play around with digital animation after Pompoko was completed, Yasuda realised that technology would have substantially reduced her workload, but also that it would lead to lay-offs. Her biography’s 1990s chapters hence detail her growing apprehension about the oncoming digital disruption. Her main contact at STAC retired, and with neither STAC nor their rivals Taiyo Shikisai giving her the paint she needs, she guiltily approached the Canadian company Chromacolour. Although she complained about their materials, she used 91 Canadian colours in Princess Mononoke, while fretting all the while that every overseas contract was another nail in the coffin of domestic industries.

“Ghibli could have been bankrupted by Princes Mononoke,” noted its unrepentant director Miyazaki. “I was conscious that it might be my last film, so I needed to shoulder more than ever. I knew this film would require tremendous time and effort from the start. So, I was absolutely fine when I was told by the producer that it would be 100 million yen in the red if I kept the density of the work until the end. I didn’t feel obliged to keep the company going… I was a slave of this piece. I didn’t care if everyone collapsed to complete this film. I was prepared to let them work without sleep for days.” Sure enough, a planned animation output of 110,000 in-between frames ballooned to over 125,000, and as always, it was the finishing section that paid the price, since every extra cel was an extra finishing job. Once again, Yasuda rang around and asked for help, but that was not enough. After her bad experience with Fireflies, she did not want to release it unfinished. She was forced to embrace digital faster than she had expected, and was then obliged to go to each of the finishing companies that had helped her, to break the news that in future, Ghibli would be getting more digital, but that “we would find the way forward together.”

The Colour Artisan of Animation, (Animation no Iroshokunin) was first published in 1997 but has been through eight printings since, the most recent under the Studio Ghibli brand. Yasuda officially retired after working on Miyazaki’s Ponyo (2008), but was invited back to work on his “final” film, The Wind Rises (2013). She died in 2016, shortly before Miyazaki curtailed his latest retirement, and announced that he would be making a new film, without the assistance of the woman he had called his “comrade-in-arms.”

Leave a Reply