Bullet Train

August 12, 2022 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

One of the carriages on the Kyoto shinkansen is a mauve hellscape of high-pitched voices and big eyes, devoted to the irritating but mercifully fictional anime mascot character Momonga. Every now and then the duelling assassins in David Leitch’s Bullet Train have to traverse it, subject to invasive entreaties to be someone’s friend or high-five a needy cartoon character.

As one might expect from the director of Hobbs & Shaw, Bullet Train is a gloriously thick-eared gangster confrontation, its Japanese source material supplying a deep vendetta stretching back an entire generation, on which to hang a multi-sided heist. Ladybug (Brad Pitt) boards the train in Tokyo to steal a briefcase. Unlike its analogue McGuffin in Pulp Fiction, we know exactly what’s in it – a stack of gold bars and dollar bills, the ransom money for half-Japanese gangster heir The Son (Logan Lerman), which also happens to be the pay-off for assassin The Hornet (Zazie Beetz), on the train to kill him. Hitmen Tangerine (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and Lemon (Bryan Tyree Henry) have to get the case and The Son to Kyoto in one piece, but there are two other assassins on the train with various motives for thwarting the plans of the others.

Multiple flashbacks and asides detail the convoluted, globe-trotting conflict that has brought all these pawns into battle at a single location, mostly unaware of the two aging gangland kings who are using them to fight, or indeed of the wildcard killer The Prince (Joey King), who knowingly announces to anyone who will listen that they are merely supporting characters in her story.

Posterity will show Bullet Train to be a minor work in the filmography of David Leitch, not a patch on his masterpiece Atomic Blonde, but certainly an enjoyably silly romp. Channelling equal portions of Guy Ritchie and Quentin Tarantino, it sets up a series of viscerally entertaining fight sequences among a cast with shifting allegiances, all building towards a climactic stand-off between The Elder (the peerless Hiroyuki Sanada) and his Russian arch-rival The White Death (the glowering Michael Shannon, understandably outclassed in the martial-arts finale).

Almost as if baiting its would-be critics, the film’s soundtrack comes loaded with Japanese appropriations of English-language songs, including “Saturday Night Fever” and “Holding Out for a Hero,” as well as Kyu Sakamoto’s “Sukiyaki”, the first Japanese song ever to make it to number one in the United States.

The film’s reception, particularly in America, has come attended by tedious accusations that it “whitewashes” Kotaro Isaka’s original novel, mainly from people who never bothered to see Fish Story, an all-Japanese adaptation of one of Isaka’s other tales, and who never complained about Golden Slumber, a Korean adaptation of another. This criticism, which doesn’t seem to have troubled the author himself, the Sony corporation that bankrolled the movie, or indeed the multi-national cast and crew (shot under pandemic conditions in California, with much effects work and animation seemingly done in India), is becoming increasingly common in modern-day cinema. It was barely a whisper when Tom Cruise took the leading role in Edge of Tomorrow (based on All You Need is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka), but had become notably louder by the time Scarlett Johansson played a bodiless, anonymous cyborg in Ghost in the Shell. I do understand the sentiment behind it – we really don’t want or need a sight like John Wayne playing Genghis Khan again, but the crime, as well as the casting, in Bullet Train is globalised and international.

That said, the same critical apparatus can be brought to bear on more structural issues within Bullet Train. Filmed largely on a soundstage in Culver City, California, its Japan is a fantasy creation by American outsiders. Much as in Michael Mann’s Blackhat or Renny Harlin’s Skiptrace, Asia is a faceless playground for the characters that wander through it, suffering massive implied collateral damage, but never quite getting in the way. It’s never really explained what happens to the conductor (Masi Oka), or where the driver has gone, while everybody seems to shrug off the likely loss of innocent lives in the climactic final reel. Japan, for much of the film, is conveniently uninhabited – the supposed reason for this is that they are on the “night” train, which somehow arrives in Kyoto at dawn (so it left Tokyo at 4am?), and for which an evil nemesis has booked out all the empty seats.

This trainspotter observation is, for me, the most obvious clue to the film’s extra-Japanese creation. The credits come barnacled with tax-credits and film funds, from all over North America, but not from Japan. Isaka’s original novel was set on a bullet train heading in the opposite direction, from Tokyo up north to Morioka – the Tohoku region, which last year was the centre of a massive Japanese boondoggle initiative to encourage tourism. If someone at the production company had noticed that and hung on to the original destination, Bullet Train might have qualified for the same sort of Japanese funding initiative that funnelled production cash at Fortune Favors Lady Nikuko, Hulla Fulla Dance and The House of the Lost on the Cape.

The original novel of Bullet Train was itself a distaff sequel to Isaka’s earlier Grasshopper (2004), which has only this year been translated into English as Three Assassins. The fact that the plot relied on incidents and connections in a separate work may have skewed some of its flashbacks in all-new directions, leading to stand-offs in South Africa, South America and Mexico, and further dragging its events away from the original. So, too, does the film’s most prominent change in characters, the gender-swapping of The Prince from male to female. But if you really want to see an all-Japanese adaptation of an Isaka novel, then there’s always Grasshopper (2015), Tomoyuki Takimoto’s movie based on the earlier book, featuring Tadanobu Asano.

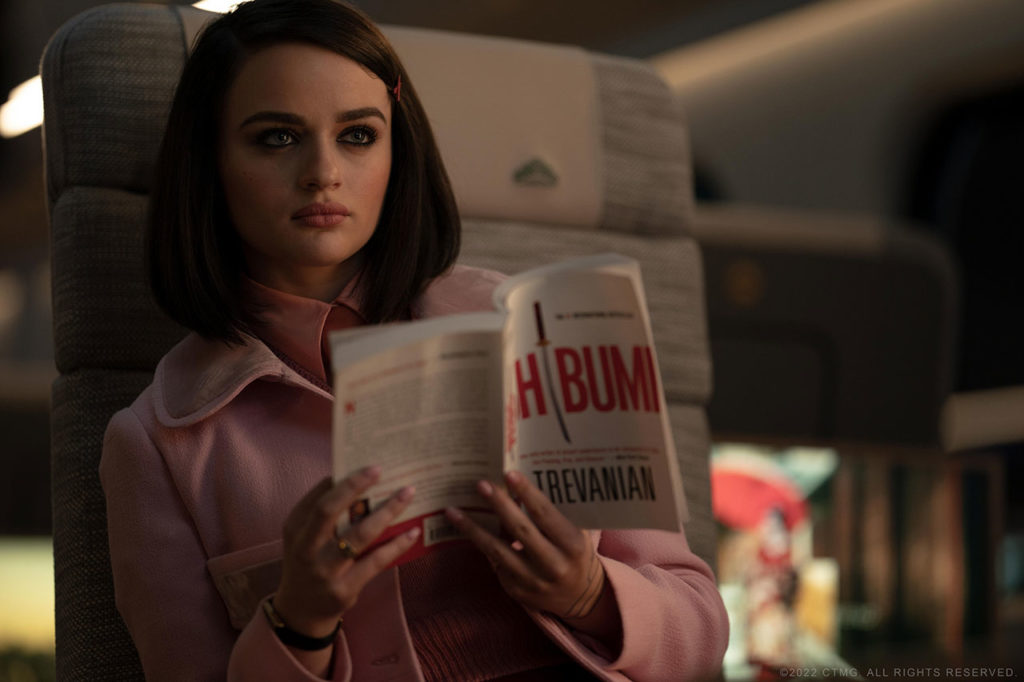

For those who desire to take Bullet Train too seriously, Leitch buries a visual admonition in his film, with the sight of The Prince reading Shibumi, a 1979 airport novel by the pseudonymous Trevanian (Rod Whitaker). Huge in its era, but largely forgotten today, Shibumi is a global conspiracy thriller about a disinherited Russian princeling who works as an assassin in East Asia… coincidentally picked up by Warner Bros in 2021 and ear-marked for film adaptation by the same 87eleven production company that also made Bullet Train. Hindsight may well demonstrate that the alterations to Isaka’s original story may have had a deeper purpose, removing it from its original context and slotting it into a shared-universe that could now include an American novel written when Isaka was only eight years old.

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of Japan. Bullet Train is showing in British cinemas now.

Leave a Reply