Children of the Sea

December 11, 2020 · 0 comments

By Kambole Campbell.

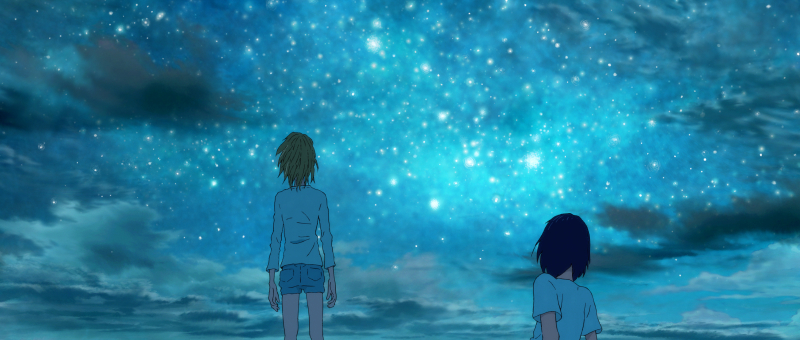

When compared to the decompressed pace of a manga series, the film adaptation Children of the Sea could never feasibly provide all the answers a viewer might seek. With a script adapted by Daisuke Igarashi from his own manga, director Ayumu Watanabe was naturally restricted as to how much of the film’s events he could explain, because for everything to be crystal clear would be to completely hold down their film with leaden exposition. Instead, Watanabe reworks the story into a tale surrounding a girl’s coming-of-age, but also leans into the confusion, turning the film’s wild final act into an almost purely sensory experience, aligning the audience with the surge of the protagonist’s own incomprehensible emotions.

Because of this, the film’s craft often feels as though it defies literal explanation. Its journey into otherworldly abstraction often obfuscates whatever the hell is actually happening. Instead of concrete answers, director Watanabe and writer Igarashi focus on sensations, communicating with image and sound where words would simply be inadequate. In an interview to be found in the Blu-ray liner notes, Watanabe said: “We understand that there are things we don’t understand… I was aiming for the border zone where a sense of the known and unknown are mixed.”

The known and the unknown mix in Children of the Sea through the personal struggles of the protagonist Ruka. Despite her verbose narration, she struggles with self-expression and connection with others, quickly establishing her isolation amid the sights of a bustling town. Though she never admits it, she unconsciously seeks for some kind of attention from somebody, as any teenager would when left as stranded as she is – her father is constantly working, her mother constantly drunk. So, the main thrust of Watanabe and Igarashi’s narrative isn’t just grand cosmic happenings and “the secret of the world”, but the young Ruka simply learning how to communicate.

The catalyst for this change in Ruka is her meeting with Umi and Sora, the mysterious brothers raised in the sea. They embroil Ruka in a mythology where nature is itself a giant body, one with its own memory – and those memories are contained within all the denizens of the ocean. Naturally, two boys who grew up among those creatures are more attuned to these cosmic truths, and reveal them to Ruka. Watanabe has the film constantly in communication with the natural world, frequently cutting to frames of animals scurrying around or even just sitting still, keeping a balance between animals and humans, a sort of serene spirituality where deities surround us in the world, rather than simply being housed in the heavens somewhere above.

This much is evident even in the tactility of the animation – chief animation director (plus character designer and technical director) Kenichi Konichi said of the film’s very deliberate use of hand-drawn animation: “Whether it’s waves or rain […], drawing them by hand means turning them into characters, which in turn means giving them a soul, in the same way as people and animals.”

Some of the most popular anime films ever made (for example, those by Hayao Miyazaki and Makoto Shinkai) have drawn on a similar Shinto-influenced belief in their depictions of the line between the spiritual and natural worlds. While it feels rote to automatically connect any anime film with those concerns to the work of Studio Ghibli, that through-line is somewhat undeniable here – Igarashi himself has admitted that Miyazaki’s film My Neighbour Totoro was a key influence on his work as a manga artist, and his tendency to imbue his folkloric fables with surrealism and spiritualism.

There’s also the matter of the film’s core creative staff, most notably former Studio Ghibli mainstay and general maestro Joe Hisaishi on duty for the film’s score, and Konichi having worked with Ghibli on similarly tactile films like The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. Watanabe and his team mix impressionism with immense detail, CG and background work give equal weight to the characters through colouring and the layouts that alternate between close-ups of faces and wide shots of each locale. The backgrounds by Shinji Kimura (who also worked on Tekkonkinkreet) all hold expansive scope and vast depth, and are presented with equal prominence to the characters, tying in with Konichi’s idea of every element of the natural world having a soul equal to humans.

Kimura’s backgrounds and Konichi’s characters also help to keep things grounded, before the film floats away into dreamlike abstraction. Other commonplace coming-of-age anime visuals help keep the film grounded – such as rituals of cooking or sports at school. Such familiarity is vital, and stops the moments of otherworldly communion from overwhelming the viewer.

The most important thing is that Ruka simply learns new ways of experiencing things, primarily though her senses, the best way for someone who struggles with words like she does. Umi and Sora, as one character says, view the world from a different perspective, place and time, and through spending her summer with them, new ways of seeing are revealed to Ruka; she learns to see ocean currents that make it easier to swim, she literally sees through Sora’s eyes as he swims away into the dark depths. The film’s priority is that sensory nature, and achieves most of it simply through the tactility of its drawings – even the use of 3DCG purposefully maintaining an almost hand-drawn quality.

After a while, the visuals shift, most dramatically during the “Birth Rite”, a (mostly undefined) communion of spirits residing in the sea and sky. Coupled with Hisashi’s swooning, synth-infused soundtrack, these sequences feel balletic in their timing of dancing lights and shapes, like something out of Disney’s Fantasia.

There’s almost a tone that recalls the films of Terrence Malick in collision between the natural world and a cosmic, higher power, people and their interpersonal problems caught in the middle and catalysing these world-changing events. Ruka’s senses are changed beyond human limitation, harmonising perfectly with the world around her – put simply, she comments “I am the universe.” There’s no dialogue to explain what this means exactly, simply the sensations of sound and light to elicit the same sense of confusion and awe that Ruka is also experiencing, that of an innate understanding of what Watanabe refers to as “the secret of the world.”

In the end, that whirlwind of a third act simply leads towards reconciliation between Ruka and the girl whom she attacked in the film’s opening minutes. By this point, it might feel that their animosity has become meaningless, petty by comparison to what Ruka (and ourselves) have borne witness to. But it’s monumental as a display of how the character has become capable of the humility and understanding to find peace with someone who she previously saw as her tormentor.

Though a lot of the film’s focus is an environmentalist spirituality that likens humans to the body of the universe, it all comes down to that simple act of communication, and self-understanding. “The children of the sea (…) tell us where we are from, where we are heading and the reason for our life.” We aren’t made privy to that reason for Ruka, not in words anyway – but we at least carry the sense that Ruka has changed (as her actress puts it, a moment of her clearly stating her intent in the second half of the film is sign of huge progress). And perhaps those experiences, and that one step forward, is enough.

Children of the Sea is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply