Eureka Seven

August 18, 2018 · 2 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

In April 2005, Japanese viewers turning on their TVs on Sunday morning were greeted by a boy on a flying board, soaring above clouds and leaving a trail of green fire, set to exuberant music. Viewers of different generations could make a range of connections. Youngsters might have linked the image to Disney’s recent film Treasure Planet, whose hero Jim Hawkins flies in a similar manner.

In April 2005, Japanese viewers turning on their TVs on Sunday morning were greeted by a boy on a flying board, soaring above clouds and leaving a trail of green fire, set to exuberant music. Viewers of different generations could make a range of connections. Youngsters might have linked the image to Disney’s recent film Treasure Planet, whose hero Jim Hawkins flies in a similar manner.

Older anime fans might remember Gainax’s 1992 epic Nadia, which also starts with clouds and flying. And really old-school fans might have linked the image to a seminal 1928 painting of a flying man by Frank R. Paul, which graced the pulp magazine Amazing Stories and defined science-fiction at its most optimistic.

Perhaps Gainax’s Nadia is the most fitting comparison Like Nadia, Eureka Seven was a serial for youngsters (who’d be watching animation at 7 a.m. on a Sunday morning), and it starts as a bright, cheerful adventure. In a contemporary interview, Eureka’s main writer Dai Sato specified “the series was aimed at children, but there are subtexts for viewers who aren’t children.”

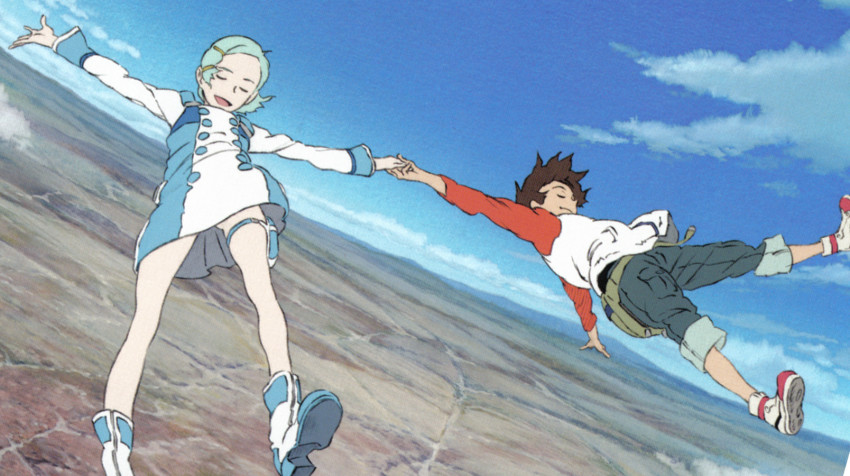

In the first episode, the sky-surfing boy, called Renton, encounters a mysterious girl, Eureka, who drops from the heavens in a flying giant robot. By episode three, Renton’s joined the legendary counter-culture group to which Eureka belongs. They’re the crew of a skyship called Gekkostate, who fight the government and surf the breeze in really cool ways.

And then… the series takes its time revealing itself. It’s not even clear for a long while whether the setting is Earth or some Star Wars distant galaxy. Renton’s world has oddly organic, fan-like slopes, and strange levitating forces called “trapars”. Renton himself is ignorant of the true stakes and conflicts in his world, and so is the viewer. Several early episodes just have Renton acclimatising to the Gekkostate and its crew, who see him not as some “First Child” at the heart of the action but rather as a child, a nuisance, better not seen or heard.

And they’re right; Renton is a child. One of his first escapades, for example, has him taking toddlers into a combat zone, in a stunt so dumb it risks losing the audience. The point, though, is precisely to highlight Renton’s immaturity and irresponsibility. Among Studio Bones protagonists, it places Renton at the opposite extreme from the similarly-aged Ed and Al in Fullmetal Alchemist, who’ve had the ghastliest lesson in responsibility imaginable.

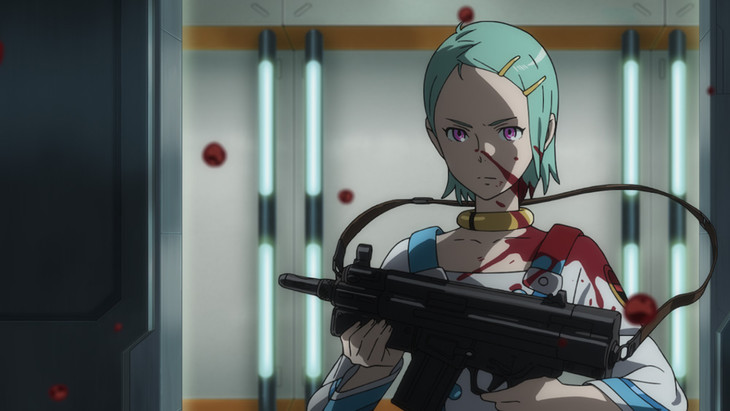

Eventually, though, Renton makes shock discoveries about his companions, bloody secrets other shows would save for their closing episodes. Then he’s launched into terrifying aerial battles, which skew into an Alice-style dream in the clouds, where Renton’s chased by a crazy girl who might be a twisted sister to Eureka. Later the slings and arrows become brutal. In another violent robot battle, Renton’s whole self-image – as a brave young hero who protects his friends, especially beautiful girl friends – explodes in a horrible way.

Eventually, though, Renton makes shock discoveries about his companions, bloody secrets other shows would save for their closing episodes. Then he’s launched into terrifying aerial battles, which skew into an Alice-style dream in the clouds, where Renton’s chased by a crazy girl who might be a twisted sister to Eureka. Later the slings and arrows become brutal. In another violent robot battle, Renton’s whole self-image – as a brave young hero who protects his friends, especially beautiful girl friends – explodes in a horrible way.

And we mean horrible, especially for Sunday morning viewing. Britain’s BBFC rated the relevant episode as 12 for “moderate violence and gore” but it would have been surely unacceptable in live-action at that category. After that, Renton embarks on a search for his identity, discovering new role-models, even trying to being a kid again.

2005 was a good year for lavish anime on TV. It was the year of Noein, by the Satelight studio, which had more than 150 key animators listed by the ANN website. Eureka, twice as long, had about 300 key animators. Its bright designs and detailed animations, highlighting character expressions as much as mecha mechanics, set a new standard on the small screen.

2005 was a good year for lavish anime on TV. It was the year of Noein, by the Satelight studio, which had more than 150 key animators listed by the ANN website. Eureka, twice as long, had about 300 key animators. Its bright designs and detailed animations, highlighting character expressions as much as mecha mechanics, set a new standard on the small screen.

In particular, Eureka was a landmark title for the Bones studio, seven years after its founding in 1998. Bones had already made a reputation with British fans, with epics like Wolf’s Rain and the first Fullmetal Alchemist. Another early Bones titles was the mecha series RahXephon. This also featured a boy whose worldview and identity is ripped apart as the story progresses. RahXephon and Eureka share pivotal scenes in which the boys fight ferociously in their mecha, fired up by their conviction that they’re protecting loved ones, only to make a sickening discovery after their “victory”.

Tomoki Kyoda was an Assistant Director on RahXephon, and directed its movie retelling (subtitled Pluralitus Concentio). Kyoda then moved up to direct Eureka Seven. He was joined by series compositor Dai Sato, who’d contributed to some of the best recent anime series – Cowboy Bebop, Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, Wolf’s Rain, Samurai Champloo and Freedom.

Both RahXephon and Eureka Seven have echoes of another series, Evangelion. Beyond their troubled boys, Eureka has an unearthly title heroine who seems intensely driven but doesn’t have a solid identity, except as a “mother” to three orphan children. In these ways (maternal side included), Eureka resembles the iconic Rei in Evangelion.

But Kyoda mentioned an older series as an inspiration; Hayao Miyazaki’s Future Boy Conan from 1978. In Kyoda’s words, it was “a story about a boy meeting a girl and how their world changes around them.” Miyazaki imagery runs through Eureka Seven, from a giant cloud formation à la Laputa, to great underground forests out of Nausicaa. Given the historic connections between Evangelion and Miyazaki, it’s fascinating to see a series cross the streams so boldly.

But beyond them, Eureka has a raft of other references and in-jokes. The best-known are the show’s nods to pop music. As Sato explained, “The different generations in the show are represented by different music cultures. The youngest generation is represented by references to dance music, techno, and house. Hip-hop represents the next generation, and rock represents the oldest generation.”

All Eureka’s episodes are named after pop tracks. A cataclysm in the show’s backstory – Eureka’s answer to Eva’s First Impact – is called the Summer of Love. The heroes’ robots are called LFOs; military robots are KLFs. Renton’s late father Adrock is named for “Ad-Rock” Horovitz of the Beastie Boys. Renton’s granddad Axl, who’s still alive and grumpy in the series, is named for Axl Rose of Guns ’n Roses. Their family name Thurston comes from Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. “The kids who are watching (Eureka) now might figure out the references when they watch it again in five or ten years,” Sato said.

Other names are miscellaneous. Renton is named after the Ewan McGregor character in Trainspotting, which is perhaps why he experiences a deadly pilot’s “high” at a pivotal moment. Two of Gekkostate’s crewmembers, Jobs and Wozl are named after Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Two more crewmembers, the ditzy girl Gidget and her boyfriend Moondooggie, have names from an iconic American surfer movie. According to Kyoda, though, Eureka’s aerial moves were inspired less by surf culture than by skating and snowboarding.

Other names are miscellaneous. Renton is named after the Ewan McGregor character in Trainspotting, which is perhaps why he experiences a deadly pilot’s “high” at a pivotal moment. Two of Gekkostate’s crewmembers, Jobs and Wozl are named after Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Two more crewmembers, the ditzy girl Gidget and her boyfriend Moondooggie, have names from an iconic American surfer movie. According to Kyoda, though, Eureka’s aerial moves were inspired less by surf culture than by skating and snowboarding.

A married couple Charles and Ray Beams, who figure overbearingly in Eureka’s middle episodes, are named after American husband-and-wife design legends, Charles and Ray Eames. The show’s second half brings in a hulking scientist character called Greg “Bear” Egan. He’s named after two different authors, Greg Bear and Greg Egan, who advanced “hard” (scientifically grounded) SF literature.

Interestingly, some of the upfront literary allusions in Eureka Seven aren’t Japanese. Moreover, like Bones’ previous Fullmetal Alchemist, they invoke modern science beside primal belief systems that would give Richard Dawkins a seizure. One SF notion floated in Eureka’s later episodes, that our reality might collapse under the weight of the intelligences in it, seems to be inspired by a 1985 Greg Bear novel, Blood Music.

Meanwhile, in place of the Dead Sea Scrolls of Evangelion, Eureka draws on a less esoteric text. The adversary in Eureka, we learn, is obsessed by The Golden Bough, a study of myth and religion written (at least in the real world) in 1890 by a Scottish anthropologist, Sir James Frazer. Unfortunately, the character’s interpretation of Bough is brutal.

Among Eureka’s Japanese voice-cast is Michiko Neya. An already seasoned actress, her past roles included the bounty hunter Irene in Gunsmith Cats, villainess Delphine in Last Exile and Riza Hawkeye in Fullmetal Alchemist. In Eureka, she voices Talho, Gekkostate’s helmswoman. Talho is part of a Bones tradition that was established before Eureka, of engaging, multi-sided, grown-up support characters who’d balance the less mature leads.

Eureka actress Kaori Nazuka would go on to play Lelouch’s blind sister Nunally in another mecha epic of the 2000s, Code Geass. Renton is voiced by another woman, Yuko Sanpei, who’d be the heroine Nakiami in Bones’ Xam’d Lost Memories. Sanpei still voices boys, though, as in the recent Snow White with the Red Hair (where she plays Ryu).

Over the next twelve years, Eureka had multiple spinoffs. A 2009 film version, subtitled Good Night, Sleep Tight, Young Lovers, was what comic readers would call an “Elseworlds”story. The characters looked the same as they did on TV, but they were alternate versions in another reality. In 2012, the TV series Eureka Seven AO, ostensibly a “sequel” (pictured above), confused fans still further. Most of its characters were new, the setting was twenty-first century Earth, and the links to the original were only explained late in the story.

Over the next twelve years, Eureka had multiple spinoffs. A 2009 film version, subtitled Good Night, Sleep Tight, Young Lovers, was what comic readers would call an “Elseworlds”story. The characters looked the same as they did on TV, but they were alternate versions in another reality. In 2012, the TV series Eureka Seven AO, ostensibly a “sequel” (pictured above), confused fans still further. Most of its characters were new, the setting was twenty-first century Earth, and the links to the original were only explained late in the story.

Most recently, this year saw the first part of Eureka Seven: Hi Evolution, a cinema trilogy. The first film expands, remixes, recaps and contradicts the original series, and heaven knows where later films will take it. But this new Anime Limited release is the original Eureka Seven, that greeted early Sunday morning TV audiences twelve years ago, with a boy on a flying board.

Eureka Seven is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Louis Patterson

August 18, 2018 11:35 pm

Greg Egan is actually australian.

Jonathan Clements

August 19, 2018 5:35 am

Corrected.