Fred Patten 1940-2018

November 13, 2018 · 1 comment

Fred Patten, who died yesterday aged 77, was one of the foundational pillars not only of anime fandom in America, but of American anime fandom’s sense of its own history. Graduating with a Masters in Library Science in 1963, Fred was already active in American science fiction fandom when he entered the job market. For much of his career, he led a double life, writing for professional and amateur fanzines and running a comics shop, while also working as a technical manual archivist in El Segundo for the Hughes Aircraft Company.

Fred Patten, who died yesterday aged 77, was one of the foundational pillars not only of anime fandom in America, but of American anime fandom’s sense of its own history. Graduating with a Masters in Library Science in 1963, Fred was already active in American science fiction fandom when he entered the job market. For much of his career, he led a double life, writing for professional and amateur fanzines and running a comics shop, while also working as a technical manual archivist in El Segundo for the Hughes Aircraft Company.

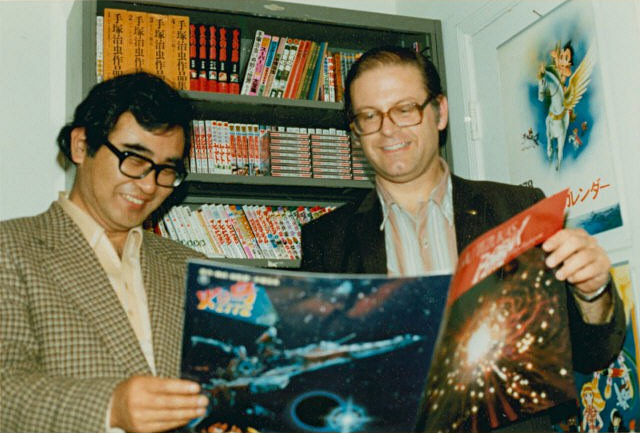

He first saw Japanese comics at an American convention in 1970, and was hooked. “One of the exhibits had the Japanese manga version of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. by Takao Saito,” he told Jason Thompson, “which was totally different from the American comic book. It went on for about three or four volumes and was very cinematic, and even though I couldn’t read Japanese, I could pretty much follow the plot through the pictures….So I went to the Japanese community in Los Angeles, and I not only found that but I discovered all the other manga they had on the shelves.” As early as 1973, he was advertising untranslated manga for sale in the Wonderworld mail order catalogue he ran with Richard Kyle.

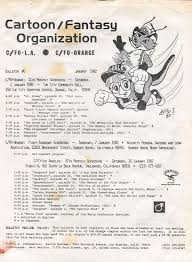

In 1976, his fellow fan Mark Merlino, an early adopter of the reel-to-reel video tape, began recording Japanese cartoons with English subtitles from local channels for the Japanese community. Merlino and Patten went on to become two of the founders of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization in 1977, America’s first anime club, in which capacity Fred worked on many early translations of Japanese works. “His literate and thoughtful translations of the dialogue,” wrote Carl Macek in 2004, “set the standard for the underground movement known as fansubs.” In a world without actual anime fans, Fred was keen to stress that anime’s origins were less important than its originality. “I don’t think that the American audience is nearly as interested in the fact they were made in Japan or that they were cartoons,” he wrote in 1994, “as that they are exciting SF adventures.”

In 1976, his fellow fan Mark Merlino, an early adopter of the reel-to-reel video tape, began recording Japanese cartoons with English subtitles from local channels for the Japanese community. Merlino and Patten went on to become two of the founders of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization in 1977, America’s first anime club, in which capacity Fred worked on many early translations of Japanese works. “His literate and thoughtful translations of the dialogue,” wrote Carl Macek in 2004, “set the standard for the underground movement known as fansubs.” In a world without actual anime fans, Fred was keen to stress that anime’s origins were less important than its originality. “I don’t think that the American audience is nearly as interested in the fact they were made in Japan or that they were cartoons,” he wrote in 1994, “as that they are exciting SF adventures.”

Fred was soon scooped up by a Japanese company, Hiro Media, which hoped to off-load straight-to-video anime on the American market, although his earnest efforts to interest American fans were hampered by two issues. “Firstly,” he wrote, “they weren’t very good.” He was particularly scathing about California Crisis, which had been conceived merely as an excuse to write off a “research trip” for the crew across the West Coast tourist sites. “Secondly, in 1986 in Japan, ‘home’ videos didn’t exist.” The early video market was intended for sale to rental stores, and meant that American fans baulked at the high price point of the videos.

When Fred turned 50, Carl Macek lured him away from his real-world job into the world of movie-making. Fred became the first employee of Streamline Pictures, with many of his early amateur scripts forming the basis for some of Streamline’s pro releases. Inevitably, he would lock horns with Macek, who would change the dialogue beyond what Fred considered to be a reasonable nuance. Fred would warn him that fandom wouldn’t like it, and as Macek later admitted, Fred was often right. However, Fred also had a fine grasp of the politics of fandom, and was instrumental in decisions designed to avoid what today might be called flame-wars. It was he who brought up the fact that the subject of the first Lupin III film, The Mystery of Mameux, had been so consistently mistransliterated as Mystery of Mamo by American fandom that correcting it would only lead to protests.

Otherwise, most of his Streamline credits were for publicity, as he travelled around conventions whipping up support for anime. One convention in Arizona began referring to its anime room as the “the Fred Patten conspiracy to get you to watch cartoons in a language you can’t understand.”

I first encountered Fred when I became the editor of Manga Max in 1998, and decided to run a history of anime fandom as one of my inaugural features. I tracked him down, by fax in those days, and we began a fruitful cooperation over numerous historical features. I also got him to write the first of the magazine’s Last Word columns, which was about the politics of fan awards. He would become a regular contributor to the magazine, hectoring me with epistolary fervour (we got through a lot of fax paper) about obscure titles in ancient anime history, and providing chapter and verse of documentary evidence with a precision born of his library training.

I first encountered Fred when I became the editor of Manga Max in 1998, and decided to run a history of anime fandom as one of my inaugural features. I tracked him down, by fax in those days, and we began a fruitful cooperation over numerous historical features. I also got him to write the first of the magazine’s Last Word columns, which was about the politics of fan awards. He would become a regular contributor to the magazine, hectoring me with epistolary fervour (we got through a lot of fax paper) about obscure titles in ancient anime history, and providing chapter and verse of documentary evidence with a precision born of his library training.

Not long after the magazine was shut down two years later, I met him in real life for the first and last time in Atlanta. He looked like an engineer escaping from the 1950s, with trousers that looked a little tight under the armpits, and a wealth of stories about the ins and out of fandom. He reminded me a little bit of Sam the American Bald Eagle from The Muppet Show, which perhaps explained why when furry fandom (in which he was also a major figure) insisted that every member had to pick a representative animal, someone picked the eagle for Fred.

He told me that it had been a pleasure for him to be allowed to poke around so many interesting areas of anime, and to get paid for it, too. It was then I realised just how much of his previous work have been done merely for love. But we kept in touch, and I asked him to be one of the beta readers on the 2001 Anime Encyclopedia. As ever, he went above and beyond the call of duty, penning messages like: “I didn’t think much of your entry on Giant Gorg, so I took the liberty of writing one myself.” His version, pretty much unchanged, still endures in the most recent edition.

He told me that it had been a pleasure for him to be allowed to poke around so many interesting areas of anime, and to get paid for it, too. It was then I realised just how much of his previous work have been done merely for love. But we kept in touch, and I asked him to be one of the beta readers on the 2001 Anime Encyclopedia. As ever, he went above and beyond the call of duty, penning messages like: “I didn’t think much of your entry on Giant Gorg, so I took the liberty of writing one myself.” His version, pretty much unchanged, still endures in the most recent edition.

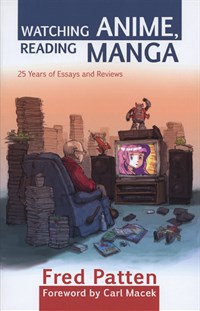

In 2004, he published a collection of his own writings, Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews, reprinting his work form Manga Max and Newtype USA, but also many obscure photostatted fanzines of the 1970s and 1980s, when information on Japan was far harder to come by. He wrote one of the first articles in English on the film that is now known as Sacred Sailors, and many forgotten pieces that, if you drill down deep enough, form the bedrock for what is now regarded in online resources as common knowledge.

In 2005, he suffered a stroke, leading him to move into assisted accommodation and to donate his fan collection of some 220,000 items, to the University of California at Riverside. He did, however, remain incredibly active in his various fandoms. The anthropomorphics world, likening him to Forrest J Ackermann in sf, has called him “Furry’s Forry”, but in the world of the otaku, he will always be remembered as anime’s First Fan.

DP

November 14, 2018 5:52 am

I loved his weekly “Forgotten Anime” column on the Cartoon Research blog, which he continued for years until March of last year. I probably learned more about anime from that column than from any other source.