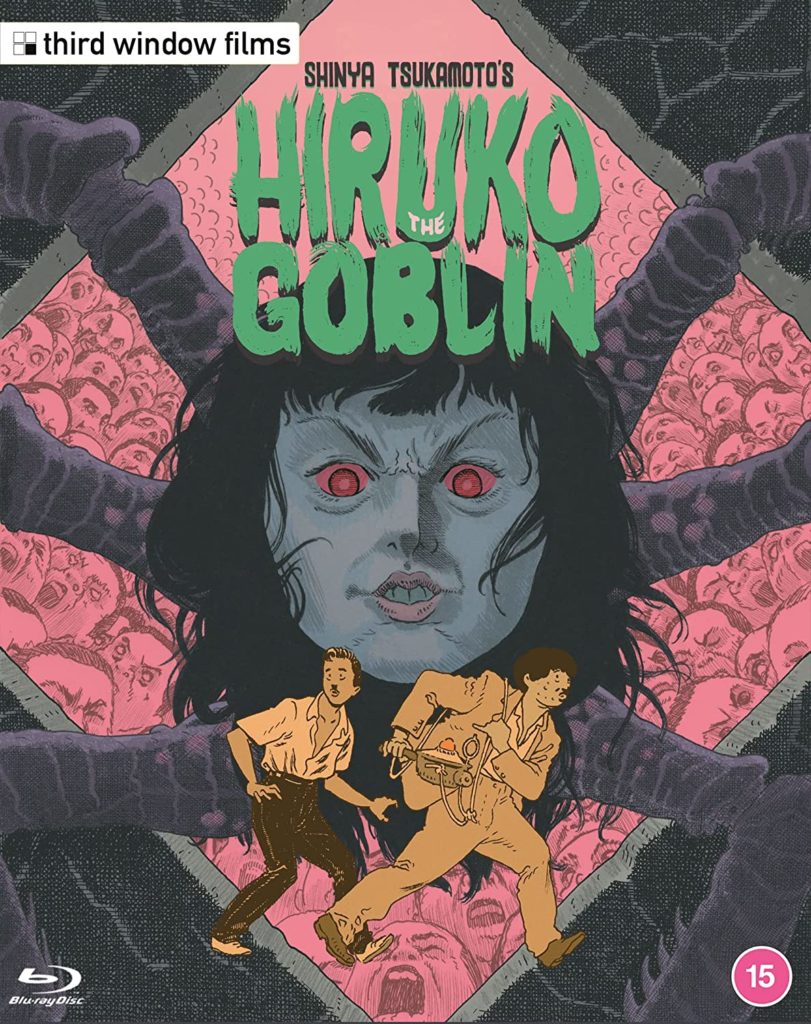

Hiruko the Goblin

April 4, 2022 · 0 comments

By Tom Wilmot.

Unhinged, abrasive, chaotic, loud; these are some of the characteristics that many have come to associate with the work of cult-favourite filmmaker Shinya Tsukamoto. Throughout his 35-year long career, Tsukamoto has left his highly stylised and instantly recognisable thumbprint on all of his films, except one – Hiruko the Goblin (1991). Marking one of the director’s rare studio endeavours, Hiruko is widely considered the ugly duckling of his body of work, with everything from its form to narrative deviating from his typical style. However, for as un-Tsukamoto-like as Hiruko might seem at first, the film has a lot more of its director in it than many may realise. Drawing on childhood obsessions and early influences, the horror is inspired by much of what drove the now acclaimed filmmaker to pick up a camera in the first place.

After his father and high-school crush mysteriously disappear, Masao (Masaki Kudou) and his chums head out to look for them. A quick scope of their school, which is closed for the summer, and a brief encounter with the lumbering groundskeeper, Watanabe (Hideo Murota), suggest that something sinister is afoot. It’s not long before Masao’s worst fears are confirmed, as his archaeologist uncle, Hieda (Kenji Sawada), arrives at the scene just in time for the two to discover that a secret tomb has been unearthed, unleashing the ancient demon, Hiruko, that threatens to destroy the world.

Those familiar with Tsukamoto’s films will note the cinematic abnormalities of Hiruko almost immediately. The traditional shot compositions and formal editing style are worlds apart from the director’s typically frantic and experimental approach. However, at this early point in Tsukamoto’s career, it was his first feature, Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), that was the exception in his filmography. The director had spent much of his formative years making 8mm films with his high-school and university pals, most of which were inspired by adventure tv-series and monster movies that entranced him in childhood. It’s easy to look back and see Hiruko as a departure from the filmmaker’s now established style, but at the time, the project marked the natural continuation of these early childhood films. It was only after Hiruko’s box-office failure that the director would return to the kinetic visual style of Tetsuo, with which he’d made his name.

Hiruko ditches the dark and dour cityscapes of the Tetsuo films for an idyllic countryside setting that is more the stuff of fantasy. Having been shot in Asahi, Toyoma Prefecture, during the summer of 1990, the film’s early scenes are dominated by lush green fields, blooming flowers, and piercing blue skies. This scenic backdrop compliments the feeling of summertime adventure at the film’s core and contrasts nicely with some of the more horrific visuals.

Rounding out Hiruko’s irregularities as a Tsukamoto project is the absence of the late Chu Ishikawa, who composed the score for the vast majority of the director’s films until his untimely death in 2017. Instead, we’re treated to a blend of stirring and sinister tracks from composer Tatsushi Umegaki, whose wicked title-card theme is a standout.

Despite the film’s competence in all areas, its virtues have been mostly overlooked due to its unique place in Tsukamoto’s filmography. The film carries the baggage of being a Shinya Tsukamoto project along with all the expectations that come with that label, which ultimately detract from its merits as a solid monster-adventure flick.

A loose adaptation of two stories from manga author Daijiro Morohoshi’s popular Yokai Hunter series, Masao and Hieda must thwart the evil demons to save the world. They make for an affable duo, with one-time rock star Kenji Sawada’s bumbling Hieda bringing an element of goofiness to the film with his makeshift goblin tracking equipment made from various kitchen appliances.

Well-versed horror fans will no doubt see the similarities between Hiruko and several popular American horror films of the 1980s, most notably Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead II (1987). As if the glorious blood-spurts and monster point-of-view shots weren’t enough, the distinctive mix of slapstick comedy and grotesque imagery is clearly evocative of Raimi’s horror classic. Rather than simply ape these past films, Tsukamoto blends their form and tone with a story that is uniquely Japanese. The story of the demon, Hiruko, originates from the Kojiki, one of Japan’s oldest historical texts. The director uses the ancient tale to expand the mythos of the outcast monster, even including passages from the original text as crucial plot devices. This distinct concoction of Japanese mythology and American style horror filmmaking results in a project that’s oozing with originality.

Allotted a studio budget for the first time, Tsukamoto had far more resources with which to work on Hiruko, and this shows through the film’s marvellous special effects. The spawn of Hiruko is rather terrifying, with the spider-like walking heads being deeply unsettling for anyone with even a tinge of arachnophobia. An archive interview with special effects artist Takashi Oda delves into the process of bringing the numerous puppets to life. “Something that is actually there feels more real than CG”, Oda states – a fact that rings especially true for Hiruko, given how well the effects have held up. Only in one instance does the film show its age, that being the floating heads sequence in the finale, which was rushed due to a budgeting error that resulted in a rare compromise from Tsukamoto.

In a new interview over thirty years on from its release, Tsukamoto recognises that many see Hiruko as the odd one out in his career but maintains a fondness for the project nonetheless. The director shares anecdotes about on-set antics and discusses the many unintentional “homages” that found their way into the film, notably the likeness between Hiruko’s spider-head and a similar creature in John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982). He touches on the fact that part of the reason he prefers independent productions, aside from total creative control, is that it allows him to start work immediately rather than waiting for the approval of a studio committee. Interestingly, though, the filmmaker mentions that he recently sent a proposal to a production committee, which could lead to an exciting and generously funded future project. Just let the man make a kaiju film already!

As with nearly all of Third Window Films’ Tsukamoto releases, Hiruko can be enjoyed with a new commentary track from Japanese film expert Tom Mes. The author, who literally wrote the book on Tsukamoto, furthers the argument that Hiruko is a significant entry in the director’s filmography, stacking up its similarities with the 2011 psychological-horror Kotoko. The commentary is filled with the usual nuggets of wisdom concerning the cast and crew, but the most interesting point of discussion is that which places the film in the broader context of Japanese horror cinema. Drawing on the early films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa and later the efforts of Hideo Nakata, Mes argues that Hiruko acts as a transitional work of sorts, bridging the gap from 1980s horror to the J-horror movement at the turn of the millennium. As always, Mes delivers a valuable commentary track that offers another perspective on Tsukamoto’s often-neglected project.

Hiruko the Goblin is appealing for everything that it’s not, and this is coming from an ardent fan of Shinya Tsukamoto. One wonders what the director’s career might have looked like had the film not bombed spectacularly at the box office. His passion for adolescent adventure stories and monster movies remains strong to this day, so there’s every chance that a similarly styled project could yet come to fruition. As it stands, Hiruko remains the exception rather than the rule when it comes to Tsukamoto’s cinema. Hopefully, with this new release, the film will be reassessed and rediscovered, not only as an essential chapter in the tale of Tsukamoto’s career but as a bloody entertaining fantasy-horror in its own right.

Hiruko the Goblin is released in the UK by Third Window.

Leave a Reply