The Story of Hong Gil-Dong

October 30, 2019 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

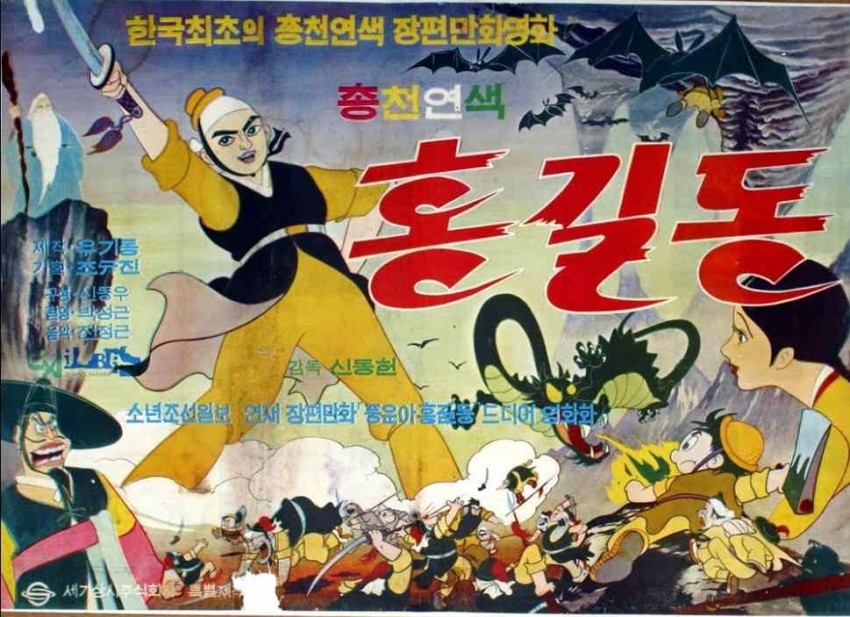

Anyone interested in world animation, and especially in how it developed in Asia, should check out an upcoming London screening of The Story of Hong Gil-Dong, a 52 year-old animated feature made in 1967. It’ll be shown at noon on Saturday 9th November at East Finchley’s Phoenix Cinema (you can book here; the film is subtitled and there are no trailers before the performance).

Anyone interested in world animation, and especially in how it developed in Asia, should check out an upcoming London screening of The Story of Hong Gil-Dong, a 52 year-old animated feature made in 1967. It’ll be shown at noon on Saturday 9th November at East Finchley’s Phoenix Cinema (you can book here; the film is subtitled and there are no trailers before the performance).

It’s not Japanese, being part of the London Korean Film Festival. What makes The Story of Hong Gil-Dong notable is it was the first animated feature ever made in South Korea, decades before the country became an animation powerhouse. Today South Korea mostly provides animation-for-hire for foreign markets, Japan included. But The Story of Hong Gil-Dong was emphatically made for a local audience, and was a massive success; around 200,000 people went to see it in the first fortnight of release.

It helped that Hong Gil-Dong was a famous character; the closest British comparison would be Robin Hood. He originated in a novel of uncertain origins and variant versions – different scholars place it in the sixteenth or the nineteenth century. Hong Gil-Dong, the illegitimate son of an aristocrat, is unjustly banished from his home. He becomes a heroic outlaw leader, stealing from the rich and corrupt and defending the poor. In the 1960s, the story was adapted as a children’s comic by an artist called Shin Dong-Woo. His elder brother, Shin Dong Hun (written Shin Dong Mun in some sources), turned this comic into the animated film.

Compressed into 67 minutes, the film plays very much as a Robin Hood variant for the first half-hour, as Hong Gil-Dong fights the cruel authorities. When he stands, legs braced arrogantly apart, on a fortress wall and challenges the powerful, it’s hard not to think of Errol Flynn’s merry man in the 1938 film.

Compressed into 67 minutes, the film plays very much as a Robin Hood variant for the first half-hour, as Hong Gil-Dong fights the cruel authorities. When he stands, legs braced arrogantly apart, on a fortress wall and challenges the powerful, it’s hard not to think of Errol Flynn’s merry man in the 1938 film.

Midway through The Story of Hong Gil-Dong, the story takes more of a Dragon Ball turn, as the hero decides he needs training and searches for a bearded warrior-sage, who puts him through trials vanquishing monsters, then duels the hero himself. By the end, Hong Gil-Dong is riding his own magic cloud into battle. This aerial skill is borrowed from the Monkey King, originally a Chinese creation but often adapted into Japanese media, including the very broad adaptation of Dragon Ball.

There are other familiar elements. A brief subplot has Hong taking time out to rescue a tiger cub from a pit, earning its mother’s gratitude. Later, the tigers repay the favour, in the tradition of Androcles and the Lion. Animation buffs will also spot what are surely references to the commercially dominant films of Walt Disney. A sequence with dancing skeletons evokes Disney’s 1929 “Silly Symphony” Skeleton Dance, though with a hilariously updated choice of music. A scene later, a green-bellied dragon menacing the hero looks like the Maleficent-monster in Disney’s 1959 Sleeping Beauty.

The Japanese influences are less on-the-nose but they do seem to be there. Back in 1967, the main Japanese animated features in cinemas were those made by the Toei studio, which created a line of fantasy and adventure stories starting with Hakujaden (White Serpent, 1958). Shin himself said he was particularly struck by Toei’s second feature animation, 1959’s Shonen Sarutobi Sasuke, called Magic Boy in America.

In several ways, The Story of Hong Gil-Dong seems more like contemporary Toei than Disney. The weight is on fights and adventure, more than character-based comedy. There are no musical numbers, barring the short skeleton performance. Another parallel with Toei is that The Story of Hong Gil Dong’s setting feels quasi-historical, rather than the fairy tale realms of classic Disney.

In several ways, The Story of Hong Gil-Dong seems more like contemporary Toei than Disney. The weight is on fights and adventure, more than character-based comedy. There are no musical numbers, barring the short skeleton performance. Another parallel with Toei is that The Story of Hong Gil Dong’s setting feels quasi-historical, rather than the fairy tale realms of classic Disney.

Actually, The Story of Hong Gil-Dong feels further removed from Disney than the Toei cartoons did. Toei’s films had Disneyesque animal sidekicks to add comedy; The Story of Hong Gil-Dong gives the same role to a homely-looking boy thief, whom Hong defeats and pairs up with. The boy is called Chadol Bawi, but many Westerners will peg him as a pint-sized Little John.

The director Shin loved Osamu Tezuka’s work, and some whimsical and weird humour in the film seems to reflect Tezuka’s cartoony humour. For example, when the hero fights off hordes of guards, we see what happens to the minions he sends flying. One flies into the mouth of a wooden carving which gulps him down; another loses his clothes to an angry pig; and a third bounces for several moments on a clothes line in defiance of gravity.

But like Tezuka’s work and so much anime since, The Story of Hong Gil-Dong will startle viewers expecting a Disney clone. The talky first scenes, for example, play up the hero’s illegitimacy, something unthinkable in a 1950s Hollywood cartoon. There’s also a (non-graphic) glimpse of a guard beating a victim, and later a villain is shown plunging fatally to earth – Disney might show the fall, but never the landing.

The oddest thing about Hong Gil-Dong is its character animation, which ignores all the fundamentals. Characters frequently slide back and forth between unnatural poses, or float, slide or slither round the frame. Some cartoon fans may find this animation unbearably crude, but it’s so “wrong” that it becomes fascinating, almost surreal.

The posters boasted the film was the product of “125,300 pictures drawn for one year by 400 people.” But production accounts make clear that The Story of Hong Gil-Dong’s makers had little animation experience – Shin had taught himself by practicing on animated commercials. Shin claimed that during the production, his staff would “make 10 minutes of animation, not like it, throw it away and do it again and again until they got it right.”

On the other hand, it seems possible that at least some of the animation’s “oddness” might have been a conscious choice. Shin commented that he was wondering “how to express Korean movements” and how to “establish the lines of our movements instead of blindly mimicking foreign works.”

Frankly, it’s hard to imagine even hardline Disney-haters defending The Story of Hong Gil-Dong’s bizarre animation as a statement of artistic independence. Then again, Shin’s comment looks poignant now, given that so much of South Korea’s animation industry today is made to service other countries.

The film’s backgrounds are less strange; the stony towns and rugged wildernesses are close to Toei’s worlds. The character designs are sound but rarely interesting, save for the hapless Chadel Bawi. Many characters, like the titular handsome hero, look like Toei’s blander figures; however the cast seems in sore need of a model sheet to sort out their poses.

Beyond its similarities to contemporary anime, The Story of Hong Gil-Dong has a surprising Japanese connection. Despite its success in South Korea, prints of the film later disappeared from the country. Kim Joon Yang, who was responsible for the film’s recovery, says it was a mystery why the film was ever “lost.” However, Kim points out this was before the home video market, where a film like The Story of Hong Gil-Dong would have surely been a bestseller.

However, following its South Korean release, The Story of Hong Gil-Dong had been exported to Japan, in a dub distributed by the Japanese branch of 20th Century Fox. Some 16mm prints of this dub were created for use in Japanese elementary schools. In 2008, Kim found two Japanese parties which held prints, a film archive and the company Digital Meme (which distributes vintage material, including a large box-set of prewar anime).

The best 16mm print, from the film archive, was used to create a new 35mm duplicate negative film. This was then synched with a Korean-language sound negative of the film, which fortunately had been preserved by the Korean Film Archive. The result was a new restored print that made it possible to see Hong Gil-Dong in its original language once more.

Thanks to Kim Joon Yang for his kind help with this article. The London Korean Film Festival 2019 runs from 1st to 14th November in London and on tour around the UK until 24th November.

Leave a Reply