Igort’s Japanese Notebooks

July 1, 2017 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Japanese Notebooks: A Journey to the Empire of Signs is somewhere between a comic strip and a picture book. Either way, this 180-page hardback, published by Chronicle Books, is a thing of beauty. It’s not a manga, being originally published in Italy, but its author Igort Tuveri has a rare distinction; he’s worked in the manga industry, seeing it from the inside. Japanese Notebooks is partly a memoir of his experience there, but it’s more a set of graphic essays and reflections on Japan’s history and culture, including anime and manga.

Japanese Notebooks: A Journey to the Empire of Signs is somewhere between a comic strip and a picture book. Either way, this 180-page hardback, published by Chronicle Books, is a thing of beauty. It’s not a manga, being originally published in Italy, but its author Igort Tuveri has a rare distinction; he’s worked in the manga industry, seeing it from the inside. Japanese Notebooks is partly a memoir of his experience there, but it’s more a set of graphic essays and reflections on Japan’s history and culture, including anime and manga.

A lifelong comic artist, the Sardinian-born Tuveri signs himself “Igort”; there’s more detail on him here. Igort, as we’ll call him, had his first works published in the late 1970s, when he was a teenager. His style burgeoned in the 1980s, with a string of adult, countercultural strips. Some involved Japan; Igort was already fascinated by the country. Then he received a “Manga Morning Fellowship” and was invited to stay in Japan for the first time.

A lifelong comic artist, the Sardinian-born Tuveri signs himself “Igort”; there’s more detail on him here. Igort, as we’ll call him, had his first works published in the late 1970s, when he was a teenager. His style burgeoned in the 1980s, with a string of adult, countercultural strips. Some involved Japan; Igort was already fascinated by the country. Then he received a “Manga Morning Fellowship” and was invited to stay in Japan for the first time.

Soon he was writing strips for Kodansha, the giant Japanese publisher, despite miscommunications from the start. On his first meeting with a Kodansha director, Igort found himself talking for hours. He didn’t realise he was expected to stand first to end the meeting; the director thought Igort was angling for more pay. The “ploy” worked. The director gave Igort three pay rises during the epic session!

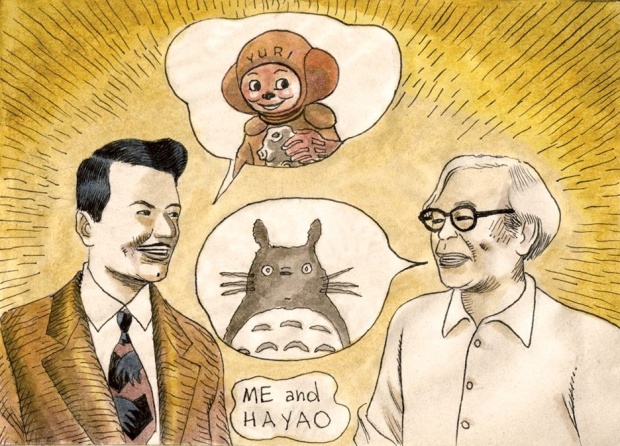

Igort’s first strip for Kodansha was an adult crime series, Amore. A portion of it is included in Japanese Notebooks, featuring highly abstract, dynamic figures. They seem to anticipate the anime segment in Kill Bill. Igort then worked on a strip called Yuri, which was not about what many of you will guess it was about. No, it was a strip about a cute little boy, popular with readers in their twenties and thirties (especially, it seems, housewives).

Many readers will be most interested in Igort’s experiences at Kodansha, although they’re only one strand of the book (and peter out about halfway). The highlight is what seems like a manga “hazing” session; it occurred when Igort had already been working in Japan for several years. He arrived jet-lagged from a flight, only for his Kodansha editor to start grilling him immediately about Yuri, and then demand a whole Yuri story, written and drawn – by the next day.

The exhausted Igort somehow managed to produce a story in his hotel room, only for the editor to read it impassively and say, “Tomorrow, another”. Stressed and angry, Igort repeated the feat, and was again told “Tomorrow, another”. In the end, he produced 160 pages of manga in two weeks… which was tossed when it was decided Yuri should be confined to its magazine’s limited colour section.

Igort balances this with an account of how supportive the editor was when Igort first started at Kodansha. But Japanese Notebooks isn’t a Bakamon-style account of writing manga. As the title suggests, it jumps around different Japanese subjects that interest the writer. It’s best not to read the book from start to finish, but rather dip into it randomly. Its subtitle refers to The Empire of Signs, a study of Japan by the French philosopher Roland Barthes. Igort describes Barthes’s book as a “travelogue composed of fragments”, which equally describes Japan Notebooks.

Many of Igort’s fragments concern anime and manga, especially in the later pages. He depicts his discovery of the war propaganda feature Momotaro Sacred Sailors and also the wartime manga Norakuro, about a dog who joins the army. He also writes of his reactions to the greatest anime about war, Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies, and of a visit to Ghibli, where he bonds with Miyazaki over notebooks.

Many of Igort’s fragments concern anime and manga, especially in the later pages. He depicts his discovery of the war propaganda feature Momotaro Sacred Sailors and also the wartime manga Norakuro, about a dog who joins the army. He also writes of his reactions to the greatest anime about war, Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies, and of a visit to Ghibli, where he bonds with Miyazaki over notebooks.

There are also brief portraits of Masashi Tanaka (Gon), Shigeru Mizuki (Gegege no Kitaro) and the more indy Yoshiharu Tsuge, a giant of the gekiga style. Osamu Tezuka is linked by Igort to Hokusai; both artists, we learn, were frustrated by incompetent engravers who messed up the faces they drew. (Igort comments, “Great art, even when made with modesty, is often a matter of eyelids, noses and ears.”) At least Tezuka could switch to the new photoengraving technology that spread in Japan in the 1940s.

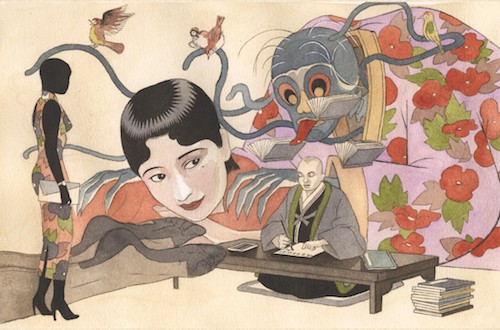

Other fragments concern subjects many readers of this blog will know. Mishima and Basho share pages with the live-action director Seijun Suzuki – Igort, a huge fan of Suzuki, finds his films hard to find even in 1990s Japan. The author Junichiro Tanazaki is celebrated by Igort, both for his aesthetics and for his scandalous erotic literature. Igort keeps his own imagery mostly tame, though there are more adult images in his twelve-page biography of a star of erotic scandal, Sada Abe – the woman who inspired Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses.

As noted earlier, the book is beautiful, mostly in colour but with occasional shifts into monochrome drawings and the odd photograph. There are visual tributes to Itoh’s heroes, including a two-page recreation of a frame from Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill, and an image of Itoh sitting quietly alongside Seita and Setsuko from Fireflies. The style ranges from elegant tableaus for the Sada Abe biography, to sometimes cartoonish portrayals of Itoh himself.

As noted earlier, the book is beautiful, mostly in colour but with occasional shifts into monochrome drawings and the odd photograph. There are visual tributes to Itoh’s heroes, including a two-page recreation of a frame from Seijun Suzuki’s Branded to Kill, and an image of Itoh sitting quietly alongside Seita and Setsuko from Fireflies. The style ranges from elegant tableaus for the Sada Abe biography, to sometimes cartoonish portrayals of Itoh himself.

The text (translated from Italian by Jamie Richards) is eminently readable. Here’s Igort discovering the aesthetics of the author Tanizaki. “I read (Tanizaki’s essay) as an initiation to that fluctuating, slowly evaporating world. Houses with shojis, sliding walls, which always created different spaces and shadows, with futons disappearing during the day, with bathrooms detached from the house, a place where the garden light flickers through rice paper walls. Faithful to the idea of the beautiful from the wabi-sabi tradition, derived from Zen, Tanizaki sang its praises.”

On the other hand, such prose can get a reader’s back up at times, if you’re averse to excess Japanophilia, or as Igort calls it, “Japan fever”. Igort’s comment that, “I had convinced myself and my editors at Kodansha that I was Japanese in a past life” will have some readers rolling their eyes. So may his uncritical references to Ruth Benedict (The Chrysanthemum and the Sword), and phrases like “I experience the present in Japan as if there’s a thin veil that lets the past shine through”. So, nothing like Igort’s experience in, say, his home Italy?

When writing about Momotaro and Norakuro, charming-looking children’s cartoons that are also war propaganda, Igort is moved: he writes, “The space of childhood is sullied, violated in its purity, by the idea of death and combat.” But anyone who’s read about the violently racist lessons that Japanese children received at school in the war years may find this comment laughably twee. The cartoons were probably the gentlest kids’ propaganda of the time.

And yet Japanese Notebooks is animated throughout by Igort’s curiosity, his urge to seek out artists and facts that don’t fit preconceived narratives. I was most surprised to find a full seven pages on the “burakumin”, Japan’s onetime caste at the bottom of the social feudal scale, whose descendants, shockingly, still suffer discrimination in Japan today. Itoh notes that as recently as 2014, feudal Japanese maps were put online by Google Earth, revealing hateful old “burakumin” place names to the world.

In this and many more ways, I found Igort’s book an education. So skip around with Japanese Notebooks; put up with its occasionally annoying Japanophilia; and admire its Mount Fuji of fine artwork. An excellent book.

Japanese Notebooks, by Igort, is published by Chronicle Books.

Leave a Reply