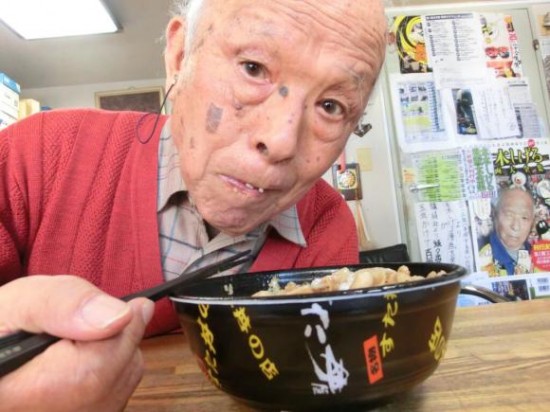

Shigeru Mizuki 1922-2015

November 30, 2015 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Shigeru Mizuki, who died today, was one of the most enduring and influential creators in the manga tradition. His career arguably pre-dated manga itself, in the chaos of the post-war period, when the young Mizuki arrived back in Japan with the world’s most unimpressive CV. Maimed in an American attack on a South Sea hospital, and cursed with an elder brother undergoing trial for war crimes, the one-armed Mizuki struggled to find work, and slummed it as a cinema projectionist. Despite his injuries, he somehow managed to get jobs drawing kamishibai, show-and-tell picture shows that were rented to travelling story-tellers, and which formed a vibrant part of Tokyo media in the days before television.

His most famous work grew out of his days in kamishibai. Beginning in the mid-1960s as Kitaro of the Graveyard, it transformed by 1967 into Gegege no Kitaro (Spooky Ooky Kitaro), the Japanese title lifting an onomatopoeic noise for all that is gross, icky and otherwise yuck. The titular Kitaro is a little boy who spends far too much time hanging out in a graveyard with his dead and undead pals, including the spirit of his own father, a disembodied eyeball who likes to dwell in Kitaro’s spare socket.

Riding an American fad for the occult and similar ghoulish gags, which saw The Munsters and Bewitched on Japanese TV screens, Kitaro soon made the jump to anime in 1968, becoming one of the few shows to enjoy runs in both monochrome and colour. A generation after the last of its episodes aired, its theme song is often reprised in karaoke and cover versions, with the gleeful claim that ghosts and ghouls don’t go to school. But it also marked the first step in what would become Mizuki’s lifelong passion: chronicling the rich traditions of Japanese ghosts. Looking up at the bookshelves in my office, I see that the largest volume on Japanese folklore I own is written by Mizuki – he has become so ingrained in Japanese urban legends that it is often difficult to extricate which ghosts are traditional and which were invented by him for his manga, without checking his own catalogues. Mizuki’s manga are riddled with celebrations of Japanese horror, including sentient umbrellas, slinky, threatening pieces of paper, and talking rats. For an entire generation of manga artists after him, he is both the inspiration and often the cited source. He is also a champion, of sorts, of both the ghosts and the tradition they represent. For it was Mizuki, in numerous interviews and essays, who argued that Japan’s supernatural creatures are in a state of permanent retreat, fleeing the urbanisation of their old haunts, and the glare of electric light. This idea, so central to the elegiac quality of his own works, has been adopted by countless other creators, and can be seen writ large in everything from Ushio & Tora to Spirited Away.

Riding an American fad for the occult and similar ghoulish gags, which saw The Munsters and Bewitched on Japanese TV screens, Kitaro soon made the jump to anime in 1968, becoming one of the few shows to enjoy runs in both monochrome and colour. A generation after the last of its episodes aired, its theme song is often reprised in karaoke and cover versions, with the gleeful claim that ghosts and ghouls don’t go to school. But it also marked the first step in what would become Mizuki’s lifelong passion: chronicling the rich traditions of Japanese ghosts. Looking up at the bookshelves in my office, I see that the largest volume on Japanese folklore I own is written by Mizuki – he has become so ingrained in Japanese urban legends that it is often difficult to extricate which ghosts are traditional and which were invented by him for his manga, without checking his own catalogues. Mizuki’s manga are riddled with celebrations of Japanese horror, including sentient umbrellas, slinky, threatening pieces of paper, and talking rats. For an entire generation of manga artists after him, he is both the inspiration and often the cited source. He is also a champion, of sorts, of both the ghosts and the tradition they represent. For it was Mizuki, in numerous interviews and essays, who argued that Japan’s supernatural creatures are in a state of permanent retreat, fleeing the urbanisation of their old haunts, and the glare of electric light. This idea, so central to the elegiac quality of his own works, has been adopted by countless other creators, and can be seen writ large in everything from Ushio & Tora to Spirited Away.

But Kitaro was by no means the sum of Mizuki’s work. His first award in the manga world was received for the now-obscure Terebi-kun, a playmate who would leap out of kids’ televisions. Ironically, this, too might have led to a horrific element in wider pop culture – could it have inspired the infamous moment in the Ring films…? Among his many other works there are titles undiscussed in English, including Salaryman God of Death, in which a jobsworth grim reaper tries to shirk on his responsibilities of bringing 12 souls a year to hell, and Monroe the Witch, an adult-oriented retelling of fairy tales, in which a blonde-bombshell sorceress attempts to assert her rightful place among a number of other iconic heroines.

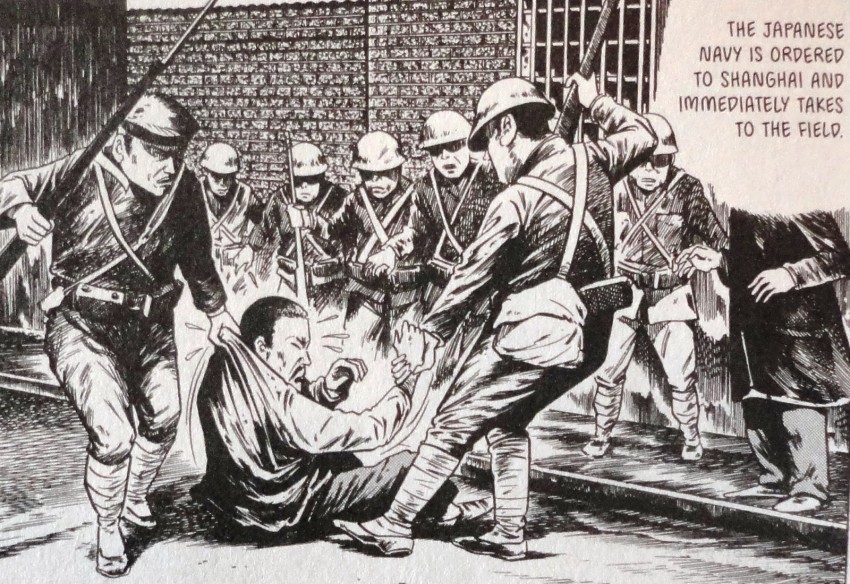

In 1989, the year of the death of Emperor Hirohito, Mizuki embarked upon his most serious work, chronicling the emperor’s entire reign. This, of course, neatly bracketed Mizuki’s own life and career before semi-retirement, allowing him to inter-weave his own horrible wartime experiences amid a more general account of Japan in the 20th century. The result was Showa: A History of Japan, which is likely to endure long after Mizuki’s contributions to folklore have been subsumed into the public domain.

In 1989, the year of the death of Emperor Hirohito, Mizuki embarked upon his most serious work, chronicling the emperor’s entire reign. This, of course, neatly bracketed Mizuki’s own life and career before semi-retirement, allowing him to inter-weave his own horrible wartime experiences amid a more general account of Japan in the 20th century. The result was Showa: A History of Japan, which is likely to endure long after Mizuki’s contributions to folklore have been subsumed into the public domain.

Other works, attached to his grand project, include a manga biography of Hitler and his military manga Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths. He also managed to include his ghost stories, too, through the memoir Nonnonba, about the early inspirations and people in his real-world childhood who led him to create an entire world of playful ghosts and friendly devils.

In death, Mizuki has literally become part of the Japanese scenery, no more so than in his home town of Sakaiminato, which is populated with statues of his most famous creations.

Gegege no Kitaro, Jonathan Clements, manga, obits, obituary, Shigeru Mizuki, Spooky Ooky Kitaro

Leave a Reply