Interview: Naoki Urasawa

June 7, 2019 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

“I have been told that the UK is one of the countries where manga hasn’t really been culturally assimilated,” declares the manga giant Naoki Urasawa. “I couldn’t quite grasp why the country which had the Beatles, who loved rock music, couldn’t understand manga.”

“I have been told that the UK is one of the countries where manga hasn’t really been culturally assimilated,” declares the manga giant Naoki Urasawa. “I couldn’t quite grasp why the country which had the Beatles, who loved rock music, couldn’t understand manga.”

If you’re read Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys, named in honour of Marc Bolan, you’ll know how deep the artist’s love of rock runs. “A lot of artists really struggled to decide whether to become manga artists or rock musicians, so the two are intertwined, they’re synonymous!”

Urasawa’s workload is legendary, yet he’s taking time out to guide a pack of journalists around the new free exhibition of his work at the Japan House London. The exhibition showcases his best-known strips, such as 20th Century Boys, a decades-crossing apocalypse saga. Preposterous it may seem, but Urasawa claims the manga is about one-tenth autobiographical, showing the memories and dreams of his 1960s childhood.

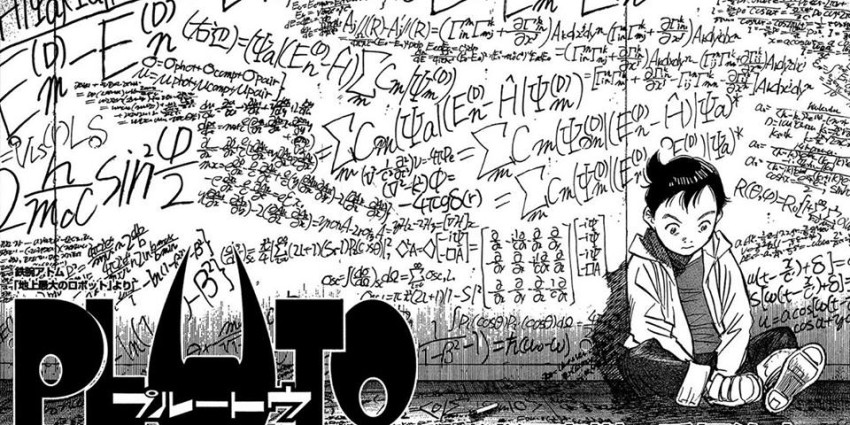

Then there’s Monster, Uraswsa’s massively feted thriller. In it, a surgeon is accused of murder, mocked by a fiend in human form, and haunted by a secret history going back to the Cold War. “My publisher was adamant that it just wouldn’t do well; they really tried to stop me,” Urasawa says. Then there’s Pluto, Urasawa’s reimagining of Astro Boy by Osamu Tezuka, but in his own style. Master Keaton relates the adventures of an unconventional insurance investigator, though that’s like calling Indiana Jones an archaeologist.

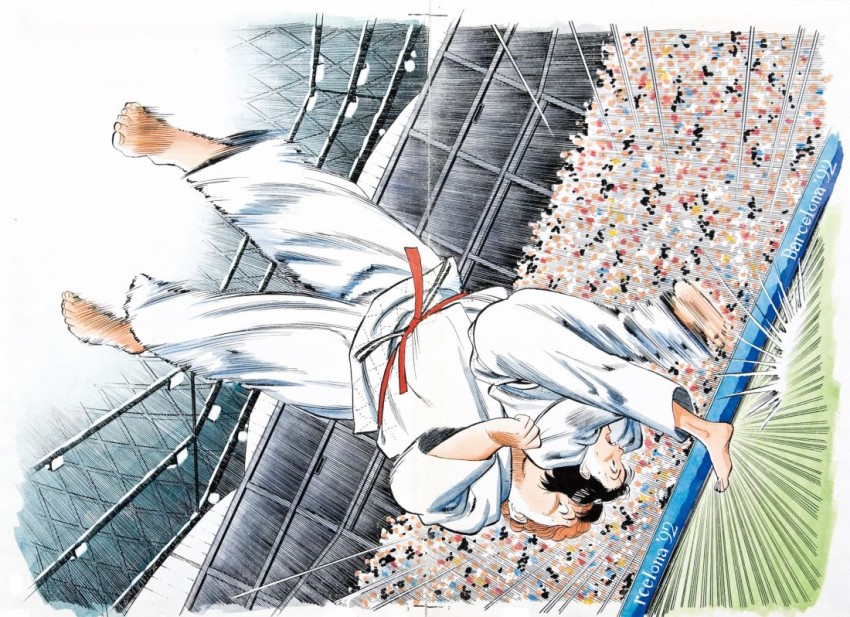

There’s also art from far earlier in Urasawa’s life, all the way back to when he was a precocious primary schooler, drawing strips with dark endings. (This was a kid who loved films like Le Trou or The Hole, a downbeat escape movie by Jacques Becker.) There are also Urasawa strips that aren’t in English yet. You may know Yawara!, about a budding girl judo fighter, from the long-running TV anime. Urasawa reflects that he began the manga in 1986, when women’s judo wasn’t popular at all. When it ended, there was a real Olympic girl medalist in Japan, Ryoko Tani. Her nickname in the Japanese media? Yawara-chan.

The exhibit in Japan House preserves the experience of reading manga, with whole chapters of Urasawa’s strips represented in the displays. Spoilers: Monster is represented by the very final chapter, though the artist explains it’s the one he put his whole soul into.

The exhibit in Japan House preserves the experience of reading manga, with whole chapters of Urasawa’s strips represented in the displays. Spoilers: Monster is represented by the very final chapter, though the artist explains it’s the one he put his whole soul into.

20th Century Boys is represented by two adjacent chapters. The first ends with a pair of big robots facing off in Tokyo. Urasawa had meant for a city-smashing battle to follow the next week. Then he looked at the TV, and saw the 9/11 attacks in New York. Consequently, the next chapter of 20th Century Boys – also on display – has no urban destruction at all. Instead it shows the manga’s protagonist singing, Urasawa’s tribute to the 9/11 victims.

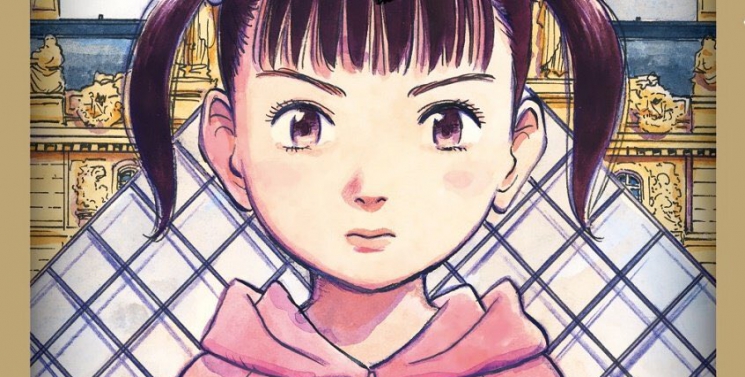

The exhibition also features more Urasawa strips not in English yet. Billy Bat, another epic (running twenty volumes in Japan) is about an artist, the cute cartoon character he draws, and a deranged global conspiracy. Mujirushi is far shorter, a miniseries which was made in collaboration with the Louvre. Like Pluto, it features Urasawa’s take on an iconic character from a past decade. This time it’s the character Iyami, created by the gag manga king Fujio Akatsuka, famed for his “Sheeh” pose.

Thanks to Japan House, I could interview Urasawa in more depth.

Yawara! was your first big hit. Was it more under the control of your editors than your later manga?

No, there wasn’t any real control by the publisher. I was speaking with my editor and I was interested in potentially writing about something in the medical field, like Monster [later on]. But as you can imagine, treating medical problems could potentially cause a lot of red lines… That’s why the editor was very cautious and the meeting itself was very serious. So within that meeting, I could tell that the editor’s face was very stern and he didn’t look very happy.

He really liked pro baseball, like many Japanese men. He’s a big fan of Fighters, and he’s very energetic talking about that team, but there was none of that energy in the meeting. So I actually said as a joke: “Why don’t I write something about women’s judo?” and then he looked up with that sparkle in his eyes, like “Oh! Really?” I really want editors to be happy, I like their reactions to be positive, so that’s really where it came from.

I’m interested that you wanted to deal with medical subjects even then!

It was the American TV series The Fugitive – not the film. [The TV version featured David Janssen and was broadcast in the 1960s; it was a massive hit in Japan.] I watched it when I was about eight. The story is that a doctor is accused of murder, the detectives are chasing him and he must run away. That storyline really had an impact on me, and that’s the original that I was trying to depict in Monster.

Through your strips, you seem to have a strong preference for adult-oriented stories, grown-up characters, and a grounding in real-world events and issues.

Through your strips, you seem to have a strong preference for adult-oriented stories, grown-up characters, and a grounding in real-world events and issues.

Even when I was a child, I didn’t like manga for children. So whenever adults around me tried to show me something aimed at children, I always thought: “They’re not taking me seriously!” So that’s why I really want children who are like me, if they exist in today’s world, to read my stories.

You’ve stressed your love of Tezuka’s manga, which can easily be mistaken for children’s fare.

That is right to a certain extent. Because Tezuka has a cuteness in his drawings, they could be seen as targeted at children, but it’s different as you say. It’s not really part of the mainstream, because of the subject matter, how it treats it, and the philosophy within it. It is actually more niche, and belongs in more of a minority field.

Another reason that I say that he’s really not part of the mainstream is that Tezuka tends to end his stories, there’s a very clear ending. Whereas if somebody’s commercially minded, they would just carry it on! Think of Astro Boy. Tezuka depicted the very clear ending with Astro Boy being strapped with a bomb and going into the sun. You wouldn’t do that if you were a very mainstream commercial manga artist. That’s partly why I always tend to end my manga, when there’s twenty volumes-worth of it.

Many of your manga have elements of mystery or whodunnit stories.

I believe the definition of “mystery” is much bigger than people think it is. For example, just a chance meeting between a man and a woman is a mystery in itself. So any story that draws people in, where there is a hinge, that is a mystery. So I always feel that any interesting ideas I have are linked to the concept of “mystery”.

Do you like “genre” mystery stories, like Edogawa Rampo or Sherlock Holmes?

I don’t actually like those traditional mystery stories as in “Let’s guess who’s done this,” the stories that would end with the detective going on and on about it, you know the ones….

Looking at your Mujirushi manga, with your interpretation of Iyami by Fujio Akatsuka (see above), I wondered if you’ve ever thought of reinterpreting Lupin III by Monkey Punch.

Looking at your Mujirushi manga, with your interpretation of Iyami by Fujio Akatsuka (see above), I wondered if you’ve ever thought of reinterpreting Lupin III by Monkey Punch.

I actually feel there are completely different Lupins: the original manga character, the Miyazaki character and any subsequent series, they’re just different people. The real Lupin for me is the one that was created by Miyazaki. Any following on from that, I kind of feel that’s not quite right, Lupin wouldn’t do that. A lot of my assistants feel the same way as well. So I feel like I understand Lupin the most and they would agree with me, and they say “Why don’t you remake it?”… So I have been told that before.

So for you the Cagliostro Lupin is the real Lupin?

No actually, that’s not true. To make it as accurate as possible, it’s the one wearing the green jacket, that’s the real Lupin. In Cagliostro, he’s already wearing the red jacket. [The Lupin in Cagliostro actually wears a green jacket, but his depiction is much softer than in the 1971 Lupin ‘green jacket’ TV series on which Miyazaki worked.]

Moving to Master Keaton, why do you have story credits on later volumes but not earlier ones?

How that series came about is that I had an idea for the characters, and it was very much based on my idea for that. It was initially thought that I would come up with all the stories as well. But at the time I was still working on Yawara!, so the editorial team was slightly concerned: “He’s still in his twenties, would he have time to come up with both stories, and finish both manga, we don’t think so. So let’s bring in some story writers.”

But the stories which the writers came up with didn’t really satisfy what I had envisioned. So instead they decided to have separate meetings about the stories, and that was used for the manga episodes. But there was a change of editors, so the intimate meetings to discuss the stories weren’t possible anymore, so I needed to take the lead on creating the stories. That’s why I was listed as a story writer from then onwards. For the last two volumes, it’s fair to say that I came up with all the stories, nobody else.

You’ve often emphasised the importance of characters’ expressions in your work. Even in your preliminary storyboards, the expressions are already there. Do you have any favourite expressive actors?

You’ve often emphasised the importance of characters’ expressions in your work. Even in your preliminary storyboards, the expressions are already there. Do you have any favourite expressive actors?

That’s a difficult question! Robert De Niro, Jack Nicholson… Those actors, they can tell so much just by the angle of the face, and also just the look in the eye. Just by their turning around, you can tell there’s something they’re holding back, something they want to say. Whenever I watch films or theatre performances, I’m not really trying to make myself, but I do notice the difference between what’s “happening” and what the (characters) are trying to say, within the face.

Several of your manga are still unavailable in English, like Billy Bat. Do you think that could change?

I believe that if there are any signs that people would like to read them, I’m sure they could be translated into English. But I do have a slight concern with Billy Bat, and possibly Mujirushi. I’m not naming names, but major animation or film studios could take offence, or maybe draw some non-existent similarities between my work and their work, so that’s a slight concern…

Are you saying that Billy Bat looks like a Disney character?

I have no intentions whatsoever of that! In Mujirushi as well, there is a presidential candidate figure who looks very similar to the current President for some strange reason, but I have no intention, that’s not really how I wrote it!

You mentioned that you’ve already been to the Stanley Kubrick exhibition in London and was impressed. Kubrick approached Tezuka about working on 2001 – do you think that could have been a good film?

That’s true, isn’t it? Tezuka was too busy, wasn’t he? There was another SF film, Fantastic Voyage, where people are miniaturised to microscopic size, and Tezuka was approached for that film as well, to be part of the art department, but he had to turn that down, too. I’ve seen the diary that Tezuka was using at the time and there was just no space whatsoever for such a project, unfortunately. [The Astro Boy Essays, by Frederick Schodt, recounts the same story,but somewhat less favourably, claiming that Tezuka felt he’d “been had” by Twentieth Century Fox, who approached him about buying the rights to the Astro Boy episode “Mighty Microbe Army”, which aired in the US while Fantastic Voyage was in production but never followed through.] It’s hard, because we can never talk about “what-if”, really. Tezuka lived in such a tightly-packed schedule, and he produced so many different works, and I do wonder that if he hadn’t been so busy, and could have focused on one story, what could he have produced? But then again, maybe he could produce such amazing works because he was so busy, because he was working in multi-faceted ways.

Some people make a distinction between “manga” and “gekiga.” Do you think the distinction is useful, and would you describe your own works as gekiga?

I would like my work to be called manga, actually. I think gekiga is just a sub-genre of manga, so that’s why I want to classify myself as a manga artist in an overall sense. I’m a good friend of Katsuhiro Otomo and he mentioned the same thing as well: I am a manga artist.

The exhibition This is Manga – The Art of Naoki Urasawa is running at Japan House London until 28th July.

Leave a Reply