Jackie Chan’s Police Stories

June 7, 2023 · 0 comments

by Jeremy Clarke.

The Police Story trilogy is a landmark of Hong Kong action cinema. As David West points out in his informative essay in the accompanying booklet to Eureka’s welcome 4K UHD release of the three films, the first was the point in Jackie Chan’s career where he broke with period dramas to make a vehicle for himself that was totally modern, set in contemporary Hong Kong rather than an historic Chinese past or even the early twentieth century of his own Project A series. Action films set in the present started to emerge in Hong Kong in the early 1980s, with a couple of them directed by Chan’s fellow former Peking Opera schoolmate Sammo Hung, who managed to secure roles for Jackie some way down the cast list in Winners and Sinners (1983) and My Lucky Stars (1985).

Both of Chan’s films Project A (1983) and Police Story (1985) were successful enough to spawn a number of sequels. In the case of the latter franchise, the third one Police Story 3 – Supercop was the undeniable high point. (Alongside their UHD release of the Police Story Trilogy, Eureka have also released a standalone Blu-ray of that particular film, which is good news for anyone who doesn’t have a UHD ready player but wants a Blu-ray copy to go with Eureka’s earlier releases of the first two films.) Among the numerous extras on the three-disc trilogy version, the PS1 disc includes an invaluable 20 minute archive interview of Chan discussing the way the film was put together. It’s the school of filmmaking where the main player has some sequence ideas he wants to put in the film, and he gets in writers to build a structure to incorporate them and make the whole thing work.

Hitchcock did it with North by Northwest, in which he wanted a story to get to the scene of a man in a cornfield being pursued by an aircraft and a chase over the presidential heads of Mount Rushmore. Ray Harryhausen famously constructed his feature films around several sequences in which stop-frame puppets interacted with live human actors.

It’s fascinating to see Chan articulating the same method of working, explaining that he wanted a scene of a car driving through destroying a shanty town, and a stunt scene involving a bus, among others, but needed to know where and how to fit them into a larger whole to make a full-length movie.

By the 1980s, the martial arts star had established himself as a comedic counterpart to Bruce Lee in Hong Kong period action movies; yet as the decade wore on, his films harked back to the two great, comedy stunt performer stars of Hollywood’s silent era, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, with whom he has been justifiably bracketed ever since. These two figures aside, there’s no one remotely like Jackie Chan in the whole of cinema. You don’t need to look any further than the first Police Story to see why.

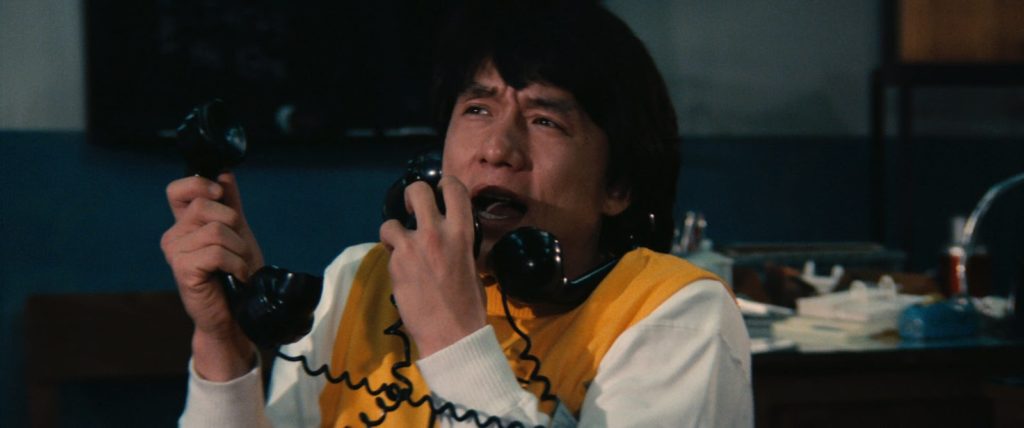

Although basically an excuse to string together an amazing sequence of stunts, directed by Chan himself, Police Story has enough of a plot to hold together as a movie. The star is cast as Chan Ka-Kui, a cop on the Royal Hong Kong Police Force, on this occasion assigned to look after the secretary (Taiwanese actress Brigitte Lin) of a crime lord the police intend to prosecute. One of its many astonishing stunt sequences, an inventive reboot of the cops-and-robbers chase, puts fleeing villains in a double-decker bus and Chan on foot. Using an umbrella handle as a grappling hook, he first attaches himself to the back of the moving bus, then hangs on to it via the open upper deck windows, with the criminals inside the bus trying to push him off it at every opportunity. Today, this might be accomplished via computer-generated effects trickery but Jackie Chan did this stuff for real. When you see him dangling off the back of a bus, hanging on with an umbrella, that is what happened before the cameras. (The umbrella in this scene was a specially fashioned prop, since the umbrellas available to buy in Hong Kong at that time would have fallen apart if you had tried to use them for this purpose.)

Alongside likeable comedy scenes between Chan and Brigitte Lin and, elsewhere, Chan and Maggie Cheung (who played his long-suffering girlfriend May in the three films) come other incredible stunt sequences. Bus chase notwithstanding, Police Story’s best stunts are found in its opening and closing scenes. In the opening, Chan drives a car through a shanty town on a hillside, his vehicle haphazardly demolishing the flimsy buildings as it goes. In the close, following a long and thoroughly entertaining fight sequence at a shopping mall, he leaps off a high-level balcony to slide down a pole to the ground. The pole is covered with illuminated electric light bulbs, which pop as his descending body hits them.

Such scenes are clearly very dangerous to film, and part of the thrill of watching them is knowing that the danger to the stunt performers is very real indeed. Chan capitalises on this by cutting together a montage of sequences that went wrong for each film – anything from comedy sequences where lines were fluffed by the actors right the way through to stuntmen getting injured when stunts don’t go quite right – and adding this to the end credits.

Maggie Cheung was seriously injured in the second film, Police Story II, when she was required to run through a series of metal, goalpost-like frames which were toppling like dominoes. The timing of the set-up was off, and towards the end of the run she received a nasty blow to the head. The film, in which Jackie’s Ka-Kui character pursues a gang of urban bombers, is entertaining enough but generally reckoned the weakest of the three.

For the third film, mindful perhaps of his own limitations as a director, Chan handed over the reins to Stanley Tong, who would go on to make such Chan vehicles as Jackie Chan’s First Strike (aka Police Story IV, and not in the current box set) and Rumble in the Bronx, the film on which Chan finally cracked the American market. The combination of Tong’s stronger sense of narrative and Jackie Chan’s determination to produce ground-breaking stunt work resulted in something that has arguably never been bettered in terms of its stunt work. (If you were looking for the best in terms of action combined with drama, that honour would probably go to the harder-hitting cops and robbers outing Hard Boiled, the last film to be made by director John Woo before he left Hong Kong for Hollywood in 1993.)

The story ventures outside Hong Kong into mainland China, with Jackie teamed up with a Chinese cop played by Michelle Yeoh (then Michelle Khan). Under Tong’s direction and with Jackie’s stunt input, she proves his onscreen equal. Already a Hong Kong action star in her own right, she would go on to major international roles including Bond movie Tomorrow Never Dies, Star Trek: Discovery and last year’s Everything Everywhere All at Once, for which she became the first Asian woman to win the Oscar for Best Actress.

Both the Chan and Yeoh characters go undercover, he as a rural-born prisoner to win the confidence of incarcerated drugs gang member Yuen Wah (another former Jackie Chan Peking Opera schoolmate), she as his sister, and following Chan and Wah’s daring break from a mining internment camp, Jackie and Michelle appear in a series of fight scenes where it often seems each is trying to outdo the other in terms of stunts. A scene at a corrupt general’s jungle encampment sees the two stars working together, including one scene where he momentarily catches her by the breasts as she falls on top of him before firing a gun at the enemy. Jackie also has a comedic sequence where Maggie Cheung’s May, working as a tour guide in Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur, spots Jackie and nearly blows his cover while Michelle tries to prevent disaster.

The two best scenes, including the one for which the film is chiefly remembered, come towards the end prior to an impressive fight between Jackie and villains atop a speeding goods train. Yeoh grabs onto the side of the van in which some of the criminals are escaping for a hair-raising ride through traffic. At one point, she raises herself up by her hands, in a move that looks like something out of ballet (in which she trained from age four until an injury curtailed that career), to avoid being hit by a close-passing coach.

You’d think this couldn’t be topped, but then Jackie leaps off a building to grab a rope ladder dangling from a helicopter carrying more villains and proceeds to fly several thousand feet above Kuala Lumpur, narrowly avoiding a mosque spire and crashing through an advertising billboard as he goes.

It’s impossible to watch these two sequences, particularly the rope ladder one, without imagining what could have gone wrong. Thankfully, nothing did. They are, quite simply, jaw dropping. For reasons of safety, they wouldn’t have been allowed or attempted in any other film industry than Hong Kong’s at that time (although the Hollywood silent era would have permitted such things had transit vans and helicopters existed then). Aided by its sense of scale – the vast, mostly empty space around its performer as he dangles over the cityscape – the helicopter / rope ladder sequence has earned its place in film history as the single most spectacular stunt ever attempted in a feature film. These days, such screen images would be realised with the aid of computer-generated effects, so the stunt’s place in the pantheon of film history is likely to remain unchallenged.

All three films come with an overwhelming array of extras, including multiple cuts and different language dubs, some with a variety of audio formats. This means, for instance, that you can watch the Hong Kong Police Story 3 cut and the shorter US cut, in Cantonese (original mono or new Dolby Atmos dub) or in American English. All three have two specially recorded commentaries. One set is by Frank Djeng (NY Asian Film Festival) and F J DeSanto, which tends to be weightier, noting, for instance, that the last reel of Police Story 3 feels like, beyond the film, flirting with death. This is where you learn that Golden Harvest wanted Stanley Tong to direct because Jackie had taken forever to complete his recent, self-directed Miracles and Armour of God. The other set is more knockabout, by action cinema experts Mike Leeder and Arne Venema, who seem to know everybody in shot and take great delight in pointing out which stunt shots of Jackie or Michelle are in fact Jackie or Michelle – and which shots are probably doubles.

All in all, this is a fantastic package and the transfers look great. For the 4K movie transfers in the box set, you’ll need a UHD-compatible player to watch them, but the standalone Police Story 3 Blu-ray is a 1080 HD presentation that’ll play on any Blu-ray player.

The Police Story Trilogy is released on UHD Blu-ray in the UK and Police Story 3 on standard Blu-ray by Eureka! Entertainment.

Jeremy Clarke’s website is jeremycprocessing.com

cinema, Eureka, Hong Kong, Jackie Chan, Jeremy Clarke, Michelle Yeoh, Police Story, Stanley Tong

Leave a Reply