Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade

March 27, 2020 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

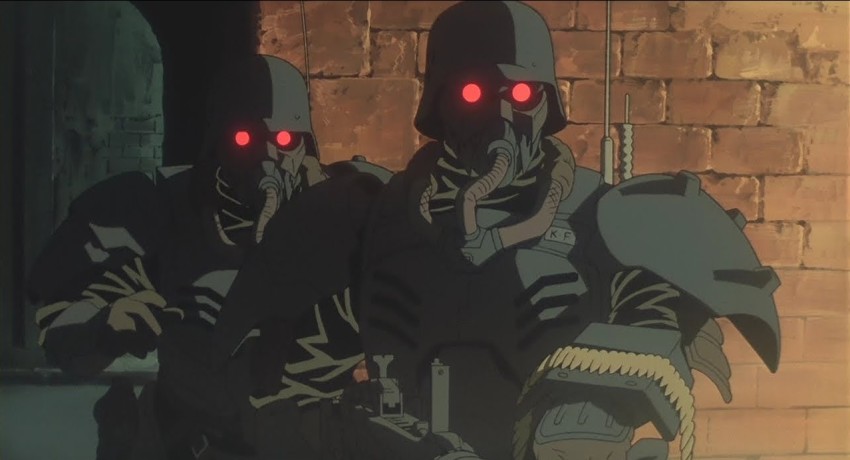

Early in Jin-roh, a young girl who’s more child than woman slumps against a wall in a sewer, a dark limbo of brick and water. She’s been running a long time, but there’s no escape. She looks up to see a soldier watching her, with infra-red eyes in a metal helmet. The girl grabs her satchel to her chest; her hand reaches to a metal ring. Jin-roh was released in 1999, when audiences might have been slower than viewers today to realise the girl’s just decided to be a suicide bomber.

Early in Jin-roh, a young girl who’s more child than woman slumps against a wall in a sewer, a dark limbo of brick and water. She’s been running a long time, but there’s no escape. She looks up to see a soldier watching her, with infra-red eyes in a metal helmet. The girl grabs her satchel to her chest; her hand reaches to a metal ring. Jin-roh was released in 1999, when audiences might have been slower than viewers today to realise the girl’s just decided to be a suicide bomber.

The soldier aims his gun, but his voice is surprisingly soft: “Don’t.” The girl’s legs shake; she starts to pull the ring. “Why?” asks the soldier. The girl shakes her head, as if imploring him for the impossible. More soldiers appear. The click of a gun’s catch is loud in the tunnel. The girl stares into the first soldier’s infra-red eyes. Then she pulls the ring hard, snapping the connected twine. She’s clumsy; the soldier has ample time to shoot, but does not. The shadows are obliterated by white light.

Jin-roh is a science-fiction film, technically, at least, set in an alternate-history version of postwar Japan. But much of Jin-roh, like the scene just described, could be set in a great many different places. It could be a story set in the carnage of Iraq in the 2000s, for example, or in cold-war Europe, or in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

The film resonates with both fact and fiction. Cinephiles will appreciate the sewer scene’s echoes of a classic British film, The Third Man, which climaxes with soldiers chasing another desperate fugitive through the sewers of Vienna. Jin-roh’s mournful theme song, created by the then-married Yoko Kanno and Hajime Mizoguchi, is a close emotional match for the famous theme music by the Irish band Clannad for the IRA drama Harry’s Game. But the real-world resonances are close or closer. This article is written while the press is full of headlines about Shamima Begum, the former British schoolgirl who ran away to jihad.

The story of Jin-roh follows Fuse, the young soldier mentioned above, who failed to shoot the girl. He survives the explosion, but is court-martialed for hesitating in the tunnel and sent back to military academy for retraining. Privately, he’s still haunted by the girl’s death and is compelled to find out who she was. He visits the building where her ashes are interred, and finds another girl there, slightly older, but incredibly similar in appearance to the one who died. She introduces herself as Kei, the dead girl’s sister, an ordinary civilian with no terror connections.

Despite Kei’s grief, she bears Fuse no ill-will. “You were both doing your jobs… Besides, they say you chose not to shoot.” Kei and Fuse continue their acquaintance, while Fuse is still plagued by his memories as he retrains at the academy. Eventually, both characters turn out to be enmeshed in a secret war between factions, but not the factions the viewer might expect.

Despite Kei’s grief, she bears Fuse no ill-will. “You were both doing your jobs… Besides, they say you chose not to shoot.” Kei and Fuse continue their acquaintance, while Fuse is still plagued by his memories as he retrains at the academy. Eventually, both characters turn out to be enmeshed in a secret war between factions, but not the factions the viewer might expect.

As noted, the film is set in an implied alternate history. It is the aftermath of World War II, and the film opens with images of Hiroshima, but it’s suggested this was a different World War, with different victors. Most obviously, the preponderance of Volkswagens suggests Japan was defeated not by the allies, but by a victorious Germany, though this isn’t confirmed in the script. Elite soldiers of this world wear immensely strong battle armour, their breathing masks erasing human features. They evoke the gear of past wars, but also the robot suits of Japanese SF.

In many ways, the film is a successor to the first Ghost in the Shell film. Like it, Jin-roh was made by Production I.G with many of the same artists, though with a crucial switch at the top. Ghost’s director, Mamoru Oshii, wrote Jin-roh’s script, but the actual director was a first-timer, Hiroyuki Okiura, barely in his thirties. In Oshii’s words, “The objective of the production side of this film was to grow Okiura into a true director, and send him out into the world.”

Even by this time, Okiura was a veteran of anime, and of a particular kind of anime, the grounded urban actioner. Okiura had animated on Patlabor 2, Akira and Ghost in the Shell. He’d gained a reputation for stunningly composed action which used buildings and other infrastructure as vividly as humans, as with the paramilitary attack on Tokyo in Patlabor 2 or the Highlander-style moment in Akira where a screaming psychic boy brings a giant beer advertisement crashing to the streets. But Okiura’s importance as a designer may be greater still. He was responsible for designing Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell, changing her from the girlish figure in the source manga into a more mature agent.

Oshii describes Okiura as someone who always had his own say, whether in design, storyboarding or the length of a scene. “He was the most troublesome staff member. But I always thought a man so into details in all areas would make a good director.” Okiura, though, was reluctant to direct a project from a work by Oshii (see below). “The story had too much of Mr. Oshii in it and I thought it would be rather difficult for other people to direct.”

Oshii describes Okiura as someone who always had his own say, whether in design, storyboarding or the length of a scene. “He was the most troublesome staff member. But I always thought a man so into details in all areas would make a good director.” Okiura, though, was reluctant to direct a project from a work by Oshii (see below). “The story had too much of Mr. Oshii in it and I thought it would be rather difficult for other people to direct.”

From Oshii’s side, “We’d worked together so long and had known each other so well that I was weary of (Okiura’s) stubbornness and Okiura was weary of my self-indulgence… We were feeling each other out as the project moved along.” The prickliness of the two men could have scuppered the film. Indeed, it was around this time that Oshii fell out with another long-term colleague, the writer Kazunori Ito, who’d scripted Oshii’s Patlabor films and Ghost in the Shell. (The company Bandai wanted Ito to script Jin-roh, too, but he declined.)

In Ito’s case, his disputes with Oshii led to an apparently permanent estrangement between the men. The situation with Okiura ended very differently. Okiura himself admitted he gave Oshii a strongly-worded condition for directing Jin-roh, half-expecting Oshii would refuse and let Okiura out of the project. Instead, Oshii accepted Okiura’s condition, which was that the film should be a largely new story, centred on a man and a woman.

Up to that point, Oshii had intended to rework elements of his manga strip, Kerberos Panzer Corps (aka Hellhounds Panzer Corps), which he’d been writing intermittently since 1988. (It was drawn by Kamui Fujiwara.) The strip depicted the alternate world shown in Jin-roh, and the factional conflicts within it. The strips themselves built on a live-action Japanese film that Oshii had directed in 1987 called The Red Spectacles; four years later, he directed a live-action prequel, Stray Dog. Oshii later claimed Red Spectacles, which has cartoon slapstick and absurdism unthinkable in Jin-roh, was annihilated by reviewers in Japan.

Jin-roh is set in an approximation of the same world, and its story uses elements from one of the Kerberos manga stories, which has fugitives in the sewers and a soldier’s fatal meeting with a woman. Okiura, though, wanted a fleshed-out romance. “He said, ‘If you write a story along this line, I will direct it,’” Oshii recalled. Oshii’s reaction surprised Okiura. “He accepted (my condition) rather readily, so now I was stuck and said to myself, ‘Okay, I have to do it.’”

Even after he accepted the role of director, Okiura would continue to butt heads with his senior about how the film’s romance should be shown. In his book on Oshii, Stray Dog of Anime, Brian Ruh quotes the co-founder of Production I.G, Mitsuhisa Ishikawa, talking about a pivotal incident. Ishikawa writes that Oshii scripted a scene in Jin-roh where Fuse and Kei go on a “date” to a planetarium. Here they talk about the constellation of the dog (presumably Canis Major), in what sounds like exactly the kind of disquisition that Oshii would use to fill much of his Ghost in the Shell sequel, to the praise of some critics but the horror of many fans.

Ishikawa claims: “Oshii likes (the Jin-roh scene) so much and he though those were the best lines in the script, this metaphorical dialogue about dogs. Okiura hated that scene. He was like ‘What the hell! This is not a love scene!’” Okiura chopped it out completely, and replaced it with a scene in the film where the couple visits a fairground on the top of a department store, talking about each other rather than stars or dogs.

Ishikawa claims: “Oshii likes (the Jin-roh scene) so much and he though those were the best lines in the script, this metaphorical dialogue about dogs. Okiura hated that scene. He was like ‘What the hell! This is not a love scene!’” Okiura chopped it out completely, and replaced it with a scene in the film where the couple visits a fairground on the top of a department store, talking about each other rather than stars or dogs.

Clearly Oshii and Okiura had different concepts of what Jin-roh should be about. One of Oshii’s central motifs was the Red Riding Hood story, which runs through the film in a savage early form. “I’ve always identified with the wolf and it shows in the film,” said Oshii. “When I had the image of Little Red Riding Hood carrying a terrorist bomb, I knew that the story was almost completed.” For Western viewers, the dream-horror presentation of the story connects with the 1984 British fantasy film The Company of Wolves, though its feminist hope is replaced by Jin-roh’s male despair.

The theme of beasts within men aligns Jin-roh interestingly with a very different source – the original James Bond novel. 1953’s Casino Royale by Ian Fleming presents 007 as having a comparable essence to Fuse, where tenderness coexists uneasily with a brutal core. Consider Fleming’s memorable description of the sleeping Bond; “With the warmth and humour of his eyes extinguished, his features relapsed into a taciturn mask, ironical, brutal and cold.” Much of this is kept in the Daniel Craig film version, seven years after Jin-roh.

More broadly, it’s easy to enjoy Jin-roh as a classically-themed film noir, full of drizzling rain and darkness – the artists strove to convey multiple kinds of dark without overt light sources. As a student in world cinema from the 1960s, Oshii surely intended Jin-roh’s multiple echoes of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, another film where a man is haunted by a woman’s death, then drawn to her double. Pushing the parallel further, both films have late scenes where characters change clothes to match gendered ideals, bowing to their inexorable masters and wiping their identities away.

The cinephile echoes of Vertigo and Third Man may have helped Jin-roh be honoured as one of the top twenty films of its year by the film magazine Kinema Jumpo, which usually disdains anime. Like Grave of the Fireflies, Perfect Blue and Oshii’s Patlabor 2, Jin-roh challenged the idea that realistic film drama was outside the purview of animation. “If you think of it as a visual storytelling in a wider sense of the word,” said Okiura, “it doesn’t have to be categorised. There is no need to be limited to either live-action or animation.” For Okiura, the freedom to make Jin-roh in animation was a point of principle, and not determined by pragmatic considerations; for example, being able to “film” a period Tokyo that had long vanished from the world.

As for Oshii, he praised Jin-roh for exceeding his expectations. “If I’d directed this, it would have been about a big dog and his mistress,” he said. “But Okiura emphasised both protagonists. It was hugely sexy as well, which I liked. I suppose the word I am looking for is ‘sensual’, but I never imagined that it would have such a flavour or such an atmosphere.”

But in another interview, though, Oshii admitted more mixed feelings. “The film is based on my concepts, story and screenplay, so substantially it is mine, but it ended up being Okiura’s film… As a director, I have to admit I regret that I did not direct it myself. The way (Okiura) directed it made it more apparent what I would have done differently. Whether it would have been better or not… Well, that’s a question for producers, not for a director.

“But, Oshii concluded, “as the writer or the project developer, I think having Okiura direct was fortunate for the film. I’m sure of it. Honestly, rarely am I moved by films, but when this film reached its last scene, I was moved.”

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. Jin-roh is released in the UK by Anime Limited.

Andrew Osmond, anime, Hiroyuki Okiura, Japan, Jin-Roh, Mamoru Oshii, Mitushisa Ishikawa

Leave a Reply