Kentaro Miura (1966-2021)

May 20, 2021 · 5 comments

“When you’re a cartoonist and working at home you sit at your desk pretty much all day,” Kentaro Miura once said in an interview. “You get most of your information about the world from the news on TV. I think that’s how most cartoonists spend their days. And then I start to see the whole picture of my point of view towards all the problems that are happening in the world. An average working man living in an average world would have a personal problem. He’d be worried about how his kids are doing in school. But I live in isolation, watching the world only on the news on TV so I start to see the bigger picture.”

Miura, who died on 6th May, published his first comic at the age of ten, writing the superhero tale Miuranger for the school magazine at his Chiba alma mater. It went on to run for 40 chapters, demonstrating an early sign of his persistent and prolific output, but also of the coterie of high school buddies that he would ultimately recycle as characters in his best-known work. “I was in a group full of people saying they wanted to be manga artists,” he remembered in 2000, “but were actually busy getting girlfriends and getting into fights, so they weren’t really all that otaku. So, I was basically the biggest manga nerd out of the bunch. It was a group of five, and I was pretty much the yellow ranger of the group: lagging behind in terms of emotional growth, but way ahead of the others in terms of drawing ability. I wasn’t capable of making a story that would really make anyone feel much of anything, though.”

He was still a teenager when he started working as an art assistant for George Morikawa, the creator of Hajime no Ippo. Morikawa, however, soon sent him away, claiming that there was nothing left for him to teach the young talent. Buronson, writer of Fist of the North Star, was in the market for an artist, and hired Miura as an assistant for himself – Miura would observe in later life that the bluster and gigantism of Fist of the North Star had been a major influence on him as a manga creator.

“When we were young and stupid,” he observed to Yukari Fujimoto, “we used to copy stuff drawn by guys like Yoshikazu Yasuhiko and Fujihiko Hosono and practice drawing manga-like pictures. We were in fine arts, though. We used to have to draw things for class and I was pretty good at it, but I wasn’t very good at manga art. So, I wanted to learn how to draw like Fujihiko Hosono, but I also wanted to make use of my realistic drawing abilities. And then meanwhile, I wanted to do an intricate story like Guin Saga, but I also liked how over-the-top [Go Nagai’s] Violence Jack was. All of that gradually coalesced into my current art style, I think.”

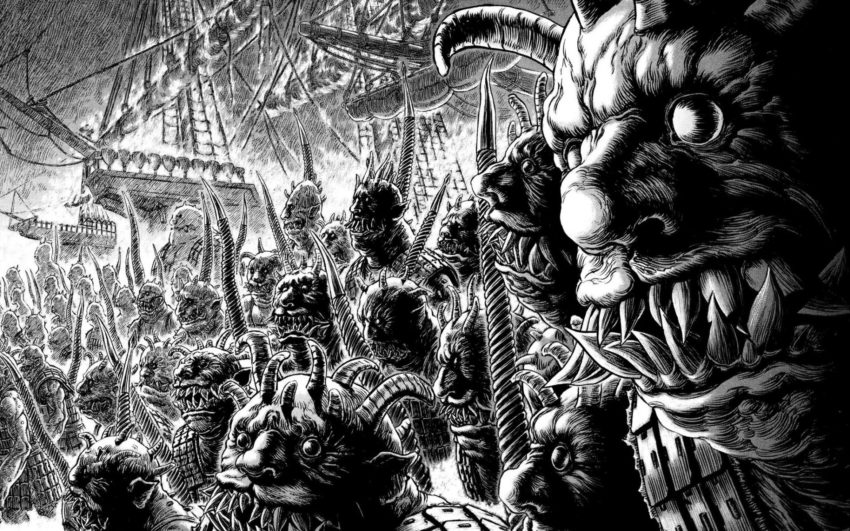

Miura used one of his own manga creations as his entrance submission for a Tokyo art school – it secured him admission, and subsequently a Best New Author prize from Shonen Magazine. Berserk was another of his competition submissions, originally conceived as a 48-page one-shot. It began running as a series in Animal House in 1989, and would become the work for which he was best known. Berserk chronicles the rise of Guts, a man in a fantasy milieu, from his orphaning at birth, through his youth as a mercenary, through to his seizure of a kingdom of his own. There are elements of Robert E. Howard’s Conan (or of his Japanese analogue, Guin) in Guts’ irresistible rise, not only in his violent career path, but in Miura’s treatment of his world as a fantasy milieu that swings widely between elements of historical Europe.

“It’s because I want to draw images of the Middle Ages in Europe,” he confessed in another interview. “When I first started my work, I actually racked my brain to decide on whether to go for a historical manga, faithfully following history, or to do a fantasy manga… Some historical elements are taken as they are. But in some parts, the age of Dracula and that of Joan of Arc have been mashed together a little bit… So European readers might say: ‘What the hell is this?’ Well, I think the way foreigners see us, Japanese people, matches this case perfectly: ‘Hey, ninjas!.’ It’s okay because I just draw my work to please Japanese people, I don’t have any strategy for the global market.”

Miura seemed to regard fantasy as something that he needed to get out of his system, noting that many manga authors he admired seemed to turn to “real” historical fiction later in the careers. But Berserk’s success would soon take over his career, becoming one of the best-selling manga of the nineties and noughties, and spinning off into an TV series and movie trilogy likened to anime’s Game of Thrones.

“Berserk was my very first manga and anime. So, I was very excited, and I wanted to make something good. I could’ve just let the studio staff do the work, but I gave some advice on the outlines of the character designs. But my main concern was the scripts. They’d send me the scripts and I’d revise them and make changes. I checked all the scripts, and made a lot of changes and requests on all of them. I bet the writers hated me.”

A less obvious parallel for the series can be found in Japan, a 1992 collaboration with Buronson, redolent of Sakyo Komatsu’s Japan Sinks, in which the Japanese archipelago is destroyed, scattering the Japanese around the world as a refugee population, clinging to a culture that is supposedly homogenous and unique, but now subject to multiple influences, persecutions and cross-pollinations. Miura would later sneak elements of that story back into Berserk, in accounts of hunts against “heretics.”

“Back then I guess it would’ve been Yugoslavia, or maybe the Tutsis and Hutus. I’m not really sure. Anyway, it made me say to myself: ‘God, the world’s a really cruel place right now.’ So, part of the idea was that I’d put in something resembling those people in order to make things a little topical. But then it’s crucial that I make it so that it’s actually about Japan – my readers are reading from a Japanese perspective, after all – and so I use the refugees to show all sorts of things like how xenophobic groups can be, or how people will refuse to act for themselves and just wait for someone else to do things for them. The idea was to expand upon the bad aspects of groups in the present day.”

Berserk was still appearing intermittently in 2021, more than thirty years after Miura began writing it. Over the decades it has gone through several transformations, as Miura develops new interests to pursue, including witch hunts, pirates, and demonic invasion. With over 40 million copies in circulation, Berserk is one of the best-selling manga ever, but its creator’s sudden death at 54 leaves its ending unsure.

“I used to have the final moves planned out, but lately I’ve been thinking I’d rather figure them out when I come to it, so now it’s hard to say what could happen. Being the sort of person I am, though, I actually don’t think I could let such a long grim story end with a grim ending – like, say, having him suddenly die. I don’t really like that kind of entertainment.”

Carl J Collins

May 20, 2021 6:54 pm

Thank you for writing this.

Romano

May 21, 2021 10:15 am

Great article

Daemon

May 22, 2021 1:04 pm

Rest in peace, may his influence still be felt past all of our lifetimes.

Dean

June 6, 2021 2:11 pm

Kentaro Miura will be missed, RIP. Berserk is by far one of the best anime ever made.

Zsoro

June 7, 2021 8:17 pm

Miura's dream lives on through Berserk, through Guts. Even if it never ends. RIP Miura ❤️ One of the best to ever do it.