Books: Kurosawa’s Rashomon

April 23, 2018 · 0 comments

By Jasper Sharp.

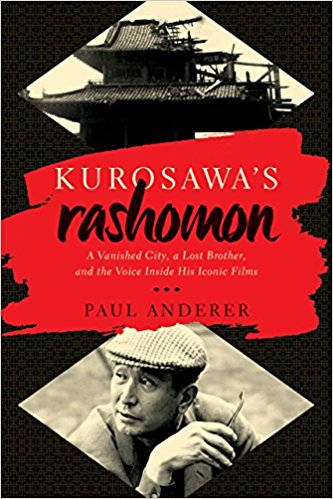

The first thought that immediately sprang to my mind when I picked up Kurosawa’s Rashomon: A Vanished City, a Lost Brother, and the Voice Inside His Iconic Films by Paul Anderer was: “Does the world really need another book on Kurosawa?” Since Donald Richie gave the West the first systematic study with The Films of Akira Kurosawa in 1973, we’ve had Stuart Galbraith IV’s The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, charting the rocky relationship between the director and his lead actor of choice; Stephen Prince’s The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa; Kurosawa: Perceptions on Life: An Anthology of Essays, edited by Kevin Chang; James Goodwin’s Perspectives on Akira Kurosawa; Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto’s Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema and Lola Martinez’s Kurosawa: Translations and Permutations in Global Cinema, to name but a few. There have been English translations of Kurosawa’s own Something Like an Autobiography; the memoirs of his production assistant Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa; and his scriptwriter Shinobu Hashumoto’s recollections of working together, Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I. And this is before we get into the numerous published screenplays and studies of his individual films, and the vast number of anthology chapters and academic journal and popular magazine articles that have appeared over the years.

The first thought that immediately sprang to my mind when I picked up Kurosawa’s Rashomon: A Vanished City, a Lost Brother, and the Voice Inside His Iconic Films by Paul Anderer was: “Does the world really need another book on Kurosawa?” Since Donald Richie gave the West the first systematic study with The Films of Akira Kurosawa in 1973, we’ve had Stuart Galbraith IV’s The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, charting the rocky relationship between the director and his lead actor of choice; Stephen Prince’s The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa; Kurosawa: Perceptions on Life: An Anthology of Essays, edited by Kevin Chang; James Goodwin’s Perspectives on Akira Kurosawa; Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto’s Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema and Lola Martinez’s Kurosawa: Translations and Permutations in Global Cinema, to name but a few. There have been English translations of Kurosawa’s own Something Like an Autobiography; the memoirs of his production assistant Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa; and his scriptwriter Shinobu Hashumoto’s recollections of working together, Compound Cinematics: Akira Kurosawa and I. And this is before we get into the numerous published screenplays and studies of his individual films, and the vast number of anthology chapters and academic journal and popular magazine articles that have appeared over the years.

One would think that within this carnival of vantage points there’s little room for a fresh perspective on the man and his movies, but Paul Anderer’s compelling account of Kurosawa’s formative years proves otherwise. Kurosawa’s Rashomon is less concerned with in-depth analyses of the films themselves than how they were informed by the family members Kurosawa grew up amongst, the books he read, the silent movies he saw, the paintings he painted and the landscapes he witnessed. Following the director’s own memoirs, the period covered is prior to Rashomon’s Golden Lion Award at Venice Film Festival in 1951, which introduced not only the name Kurosawa to the West, but gave rise to a new wave of international appreciation for Japanese cinema. However, the main emphasis is on the 1920s, long before Kurosawa directed his first feature, Sanshiro Sugata in 1943, and at during a period of his life when he was dreaming of other creative endeavours outside of the film industry.

Born in 1910, Kurosawa was in his early teens when he witnessed the devastation of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Anderer evokes a pivotal scene from the biography when he is frog-marched by his insistent elder brother Heigo on a trek across Tokyo to witness the “throng of corpses” bobbing around in the Sumida river in its aftermath: “I felt my knees give way as I started to faint, but my brother grabbed me by the collar and propped me up again. He repeated, ‘Look carefully, Akira.’”

Born in 1910, Kurosawa was in his early teens when he witnessed the devastation of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Anderer evokes a pivotal scene from the biography when he is frog-marched by his insistent elder brother Heigo on a trek across Tokyo to witness the “throng of corpses” bobbing around in the Sumida river in its aftermath: “I felt my knees give way as I started to faint, but my brother grabbed me by the collar and propped me up again. He repeated, ‘Look carefully, Akira.’”

It was not the boy’s first experience of death, nor his last on such a scale. The youngest of eight siblings, when he was nine a mysterious sickness stole the life of his favourite sister Momoyo, then aged sixteen, who had entertained him with shadow plays using lanterns and dolls that he later described as “the essence of black and white filmmaking.” Heigo himself, four years his senior, committed double suicide with a Ginza barmaid at a hot spring resort in July 1933, having left the family in his mid-teens to lead a dissolute life, first finding employment as a writer of chirashi film programme notes and later as a benshi, or silent film commentator. It was a field in which he gained some renown: after adopting the stage name Suda Teimei he rose up the ranks to become the headline performer at one of Tokyo’s grandest theatres for foreign films. Perhaps it was the coming of sound, threatening the entire profession of the benshi, that prompted the decision to take his own life? Perhaps it was the same romanticised image of leaving the material world that had led to Ryunosuke Akutagawa, one of the period’s most prestigious literary trailblazers and the author of the two short stories adapted into the script of Rashomon, to kill himself in 1927. Perhaps it was the era or increased social conservatism and state control that displaced the flourishing and dynamic avant-garde art scene of the previous decade and drove the country onwards into a destructive war. In any case, in 1945, Akira Kurosawa once more found himself gazing across the flattened landscapes of a Tokyo riddled with death following the American firebombing of the city.

Unsurprising, then, that the shadow of death should loom so heavily across Kurosawa’s cinematic output, from the central rape and murder that begins the mystery of Rashomon through the terminal illness of the lowly town bureaucrat in Ikiru, right up to his directorial swansong with Madadayo, a celebration of the final years of the writer Hyakken Uchida in his dotage. Interestingly, however, Anderer notes that despite the ghastly experiences of the director in his youth, scenes of violent demise remain largely absent from the screen: even in Kurosawa’s period films, there is not a single scene of seppuku, the “honourable” death of a samurai.

Absence manifests itself in Kurosawa’s films in other ways. The director had intended that the Rajo gate that forms the arena for the murder witnesses’ testimonies in Rashomon was to be surrounded by hordes of ramshackle market stalls, of the yamaichi or “black market” types that crammed the streets of Tokyo during the privations of the Occupation. Kurosawa had unfortunately lavished all the design budget with his fastidious reconstruction of the long-demolished southern entrance to the old capital of Kyoto. The overspend called for a simpler, more symbolic approach, and this is what shaped the opening image of the dilapidated structure, lashed by rain and isolated in the darkness, establishing the film’s unique and memorable mood (“… strikingly abstract, along the lines of an Abe Kobo novel – another allegorist foraging through the shadows and the hollowed-out emptiness of the postwar period.”)

It is Heigo’s absence from Kurosawa’s later life that is most profound. It was Heigo who had nurtured the teenage Kurosawa’s love of the translated English, French, German and Russian literature that filled the shelves of the Maruzen bookstore near Kyobashi, a “cultural emporium [that] had become a major point of contact between Western authors, Japanese writers, and the ‘literary youth’ of the day, with whom Kurosawa would come to self-consciously identify”, which itself was destroyed in the 1923 earthquake. It was Heigo who first led his younger brother into the cinemas where another passion was born: Kurosawa’s biography lists the hundreds of silent movies he watched on such excursions between 1919-29, from directors as wide-ranging as Cecil B. deMille, John Ford, Sergei Eisenstein, F.W. Murnau, Abel Gance and Buster Keaton as well as numerous long-lost Japanese titles. It was Heigo who guided him through the new wave of emerging Japanese modern writers such as Akutagawa and Yasunari Kawabata “who hoped to record the speed and the sudden ‘cuts’ of modernity in their own prose.” And it was through Heigo that Kurosawa became aware of foreign artists such as Millet, Cezanne and Van Gogh, whose paintings were introduced to Japan in reproduction in the influential literary magazine Shirakaba (White Birch).

It is Heigo’s absence from Kurosawa’s later life that is most profound. It was Heigo who had nurtured the teenage Kurosawa’s love of the translated English, French, German and Russian literature that filled the shelves of the Maruzen bookstore near Kyobashi, a “cultural emporium [that] had become a major point of contact between Western authors, Japanese writers, and the ‘literary youth’ of the day, with whom Kurosawa would come to self-consciously identify”, which itself was destroyed in the 1923 earthquake. It was Heigo who first led his younger brother into the cinemas where another passion was born: Kurosawa’s biography lists the hundreds of silent movies he watched on such excursions between 1919-29, from directors as wide-ranging as Cecil B. deMille, John Ford, Sergei Eisenstein, F.W. Murnau, Abel Gance and Buster Keaton as well as numerous long-lost Japanese titles. It was Heigo who guided him through the new wave of emerging Japanese modern writers such as Akutagawa and Yasunari Kawabata “who hoped to record the speed and the sudden ‘cuts’ of modernity in their own prose.” And it was through Heigo that Kurosawa became aware of foreign artists such as Millet, Cezanne and Van Gogh, whose paintings were introduced to Japan in reproduction in the influential literary magazine Shirakaba (White Birch).

Kurosawa himself started out on his professional career as a painter. After failing to get into the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, he became drawn to the vibrant of the proletarian arts movement, whose practitioners had come to see “culture as a construction project (especially after the earthquake), the artwork as an action to grapple with, not an object to contemplate in repose.” He exhibited five works at the second All-Japan Federation of Proletarian Arts exhibition, held in December 1929, including his massive watercolour ‘Meeting at the Construction Site’, a black-and-white photo of which is reproduced in Anderer’s book (none of the original exhibited works survive). One of the movements leaders, Toki Okamoto later described it as “a depiction of a struggle at a construction site… what struck me about it were the many contentious lines criss-crossing over the entire surface… if we look at the scale and the layered depths of his paintings from that time, we can detect the beginnings of an artistic vision that is evident in his films.”

Nevertheless, within a couple of years the government began clamping down viciously on proletarian authors, painters, filmmakers and anyone involved in promulgating foreign-derived messages and ideas that threatened the dubious concept of “national polity”. Struggling to make a living as an artist anyway, Kurosawa found his haven at P.C.L. studios in 1935, which was merged the following year to form Toho.

Given the wealth of these international influences, it is somewhat ironic that the triumph of Rashomon in Venice, the film that “marked the victory of beauty over the beast of Japanese shame” should lead to such sour-graping from critics and fellow filmmakers back at home. His work, and by extension the agitated acting style of Toshiro Mifune contained within it, was frequently denounced as “un-Japanese”, an accusation that many a Western scholar of Japanese cinema have also levelled at Kurosawa.

That Kurosawa’s Rashomon is such a page-turner is not only due to the turbulent trajectory of its subject’s early life. Anderer’s background as a scholar of Japanese literature, rather than its cinema, undoubtedly helps, as does the fact that although scholarly in its approach, the book is aimed at a more general readership than a purely academic one. The author writes incredibly well compared to many film specialists. The prose is readable, evocative, poetic and informative throughout. There are no cold and clinical dissections of individual films, nor paragraphs of theorising pockmarked by footnotes. In fact, there are no footnotes at all, although there is an exhaustive seven-page timeline of events stretching from the beginning of the Heian period in the 8th century up to Kurosawa’s death on 6th September 1998, a complete filmography and a further reading section listing both English and Japanese sources. Ultimately Kurosawa’s Rashomon does a wonderful job of fleshing out the historical and cultural context in which Kurosawa grew up, encouraging one to go back and revisit his films with new eyes.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema and can be heard discussing Rashomon on Radio Three this Wednesday. Kurosawa’s Rashomon is published by Pegasus.

Leave a Reply