Manga at the British Museum

May 24, 2019 · 0 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

The case against putting a Manga exhibition in the British Museum was made in three papers – The Guardian, The Telegraph and The Times – on the morning I visited it. Actually, one argument was effectively made before the exhibition was announced. In 2017, the Independent newspaper ranted against the British Museum displaying American pop art, “the near perfect embodiment of everything that is most silly, most trivial and most dispensable.” It could have been copied and pasted to diss the manga event.

The case against putting a Manga exhibition in the British Museum was made in three papers – The Guardian, The Telegraph and The Times – on the morning I visited it. Actually, one argument was effectively made before the exhibition was announced. In 2017, the Independent newspaper ranted against the British Museum displaying American pop art, “the near perfect embodiment of everything that is most silly, most trivial and most dispensable.” It could have been copied and pasted to diss the manga event.

Manga isn’t even pop art, of course; it’s pop culture. Most of it is especially ephemeral pop culture. Manga is churned out at industrially-driven high speed, as the new exhibition itself shows. By any plausible definition of what “manga” is (as opposed to its precursors and inspirations), it’s been around no longer than American and British comics, with no special claim to antiquity.

So why give manga deserve a whopping exhibition in the British Museum? Perhaps there’s a case that it’s a big hairy medium that’s had a palpable impact on millions of people across several generations and four or five Japanese “eras”, in a far-away country very different from ours. Perhaps; but luckily I don’t have to make that argument.

Nor, given I’m writing for anime and manga fans, need I worry about the Telegraph’s gripe that the exhibition feels – horrors! – like the work of a superfan, “pounding out the topography of the subject’s terrain without bothering to explain why we might wish to explore it in the first place.” Actually there’s a non-fan group who might like such a tour. I’m thinking of the parents of manga fans who find their offspring’s interest inscrutable and would appreciate a guide.

Anyway. For anyone who does have at least a moderate interest in manga, and its evolution through the last century, then this exhibition is terrific. I’m not measuring it against Rodin and the art of ancient Greece, which was the last exhibition to fill the same space in the Museum, the Salisbury Gallery. Rather, I’d measure the Manga exhibition against a 2015 Gundam exhibition in Tokyo, or a display of Ghibli animation layouts in Paris. By those yardsticks, the Manga Exhibition is absolutely worth the price of admission (see the bottom of this article if you’re wondering about that).

The exhibition is stupendously comprehensive and rewarding, for anyone interested in the story of manga. Of course it can’t be exhaustive – we’ll get to the omissions – but it covers a heck of a lot. It covers vintage manga, proto-manga, and pioneering manga. It goes through the megahits, but also manga genres and artists which are chronically underrepresented in Anglophone territories.

The exhibition is stupendously comprehensive and rewarding, for anyone interested in the story of manga. Of course it can’t be exhaustive – we’ll get to the omissions – but it covers a heck of a lot. It covers vintage manga, proto-manga, and pioneering manga. It goes through the megahits, but also manga genres and artists which are chronically underrepresented in Anglophone territories.

And it does this in display after display, with seemingly every one showing off the creators’ original drawings, with concise explanatory captions. Manga is rightly criticised for its repetitive drawing styles, but there’s a gratifying level of diversity here, individual visions shining through the factory process.

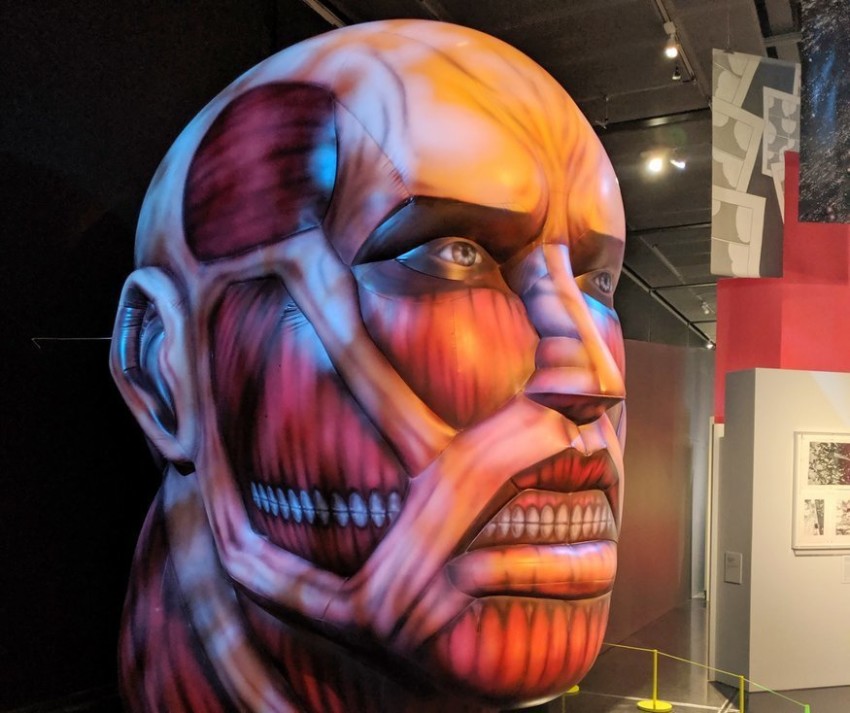

A warning…. The current big hits, like One Piece, Naruto, Jojo and Attack on Titan are represented in comparatively small displays. Titan is also “represented” with a life-sized crimson Titan head for selfie purposes; it’s a handy meeting spot, too. There are larger displays for Astro Boy, Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon, juxtaposing manga and anime versions. You’ll see plenty of the period adventure Golden Kamuy by Satoru Noda, whose Ainu heroine Asirpa is all over the posters for this exhibition. However, if there was any Death Note or Hunter x Hunter, I missed them.

The exhibition isn’t a fan nostalgia fest, except for visitors from Japan who’ve grown up with everything. Rather, it’s a way for us to learn about the less-hyped titles that we missed reading, and the titles we only heard about or saw mentioned in books like Frederik L. Schodt’s Manga! Manga!.

The first part of the exhibit is about manga’s “basics”. Quirkily, it starts with Alice in Wonderland, as envisioned in different ways by CLAMP, Otomo and Yukinobu Hoshino. Fumiyo Kono, who you may know for her wartime-Hiroshima strip In This Corner of the World, transforms Tenniel’s White Rabbit into a lovely frisky mascot which pops up to jolly us along (cowering in the horror manga section, for instance).

The exhibit wades into academic controversy early, with a video of Tezuka claiming that manga has links all the way back to Japan’s twelfth-century Animal Scrolls. This is the kind of claim to have some historians rolling their eyes and retorting, “Yes, and the Beano was descended from the Bayeux Tapestry.” But the exhibit doesn’t push this line – a caption just says tactfully: “This idea is debated among manga fans.”

Rather, the exhibit makes the less contentious point that Japan’s art of previous centuries formed a cultural seed-bed for what became manga. There’s an interesting little bridge; a hanging silk scroll from 1876 by Kitazawa Rakuten which humorously homages the Animal Scrolls. Rakuten was one of the most celebrated Japanese cartoonists in the early twentieth century, and a plausible precursor to manga now.

More dramatically, the exhibit includes a 17-metre long curtain from a kabuki theatre, dating from 1880. It depicts kabuki stars of the day as Japanese ghouls and goblins, bringing yokai and cartooning together spectacularly sixty-odd years before the rise of Tezuka.

Other highlights of the exhibit’s early sections include amusing guides to reading manga in the spirit of Scott McCloud. There’s also an excellent display dedicated to manga as an industry. Videos show time-lapse images of life in a manga office, and comments by hard-worked executives like Osamu Yoshiba of Kodansha. Yoshiba talks of the time when other American publishers thought it was “nonsensical” for Tokyopop to try selling an unflipped Sailor Moon to the American market. Tokyopop made the right call; the manga market was never the same. [Although Tokyopop was not the first overseas publisher, or even the first American publisher, to print manga unflipped – perhaps the hype has won out].

Other highlights of the exhibit’s early sections include amusing guides to reading manga in the spirit of Scott McCloud. There’s also an excellent display dedicated to manga as an industry. Videos show time-lapse images of life in a manga office, and comments by hard-worked executives like Osamu Yoshiba of Kodansha. Yoshiba talks of the time when other American publishers thought it was “nonsensical” for Tokyopop to try selling an unflipped Sailor Moon to the American market. Tokyopop made the right call; the manga market was never the same. [Although Tokyopop was not the first overseas publisher, or even the first American publisher, to print manga unflipped – perhaps the hype has won out].

Other displays show cultures crossing. The Japan Punch introduced British-style satirical cartooning to Japan in the 1860s. Tezuka’s landmark 1947 New Treasure Island, written eighty-odd years later, is displayed alongside a classic American comic, Carl Barks’ Donald Duck, which was the kind of comic that might be brought over by American servicemen in occupied Japan. Decades after that, there are collaborations between artists from east and west. The exhibition highlights Icaro, drawn by a manga artist (Jiro Taniguchi) but scripted by French comics legend Moebius.

By now, the exhibit is free-form, letting you to roam randomly, though there are distinct “zones.” You can make a circuit of the gallery walls, checking out the blow-up pictures from Dragon Ball, Jojo, and Golden Kamuy. Look up and you’ll see more oversized pictures and banners dangling from the ceiling. An overhead audio-video display based on the Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure strip by Yukinobu Hoshino gives a fair sense of how readers get immersed in adventure manga.

Among the “available but you may have missed” strips are large displays on Akiko Higashimura’s Princess Jellyfish, about female geekdom; My Brother’s Husband, the acclaimed gay drama by Gengoroh Tagame; Hikaru Nakamura’s Saint Young Men, in which Jesus is pals with Buddha; and the horror manga Spiral by Junji Ito.

You’ll find art from the original of Tekkonkinkreet manga by Taiyo Matsumoto and Miss Hokusai by Hinako Sugiura. Takahiko Inoue’s basketball Slam Dunk is honoured with some especially dynamic artwork, beside Inoue’s more recent REAL, about disabled players. The REAL characters are also the subject of a specially-drawn triptych by Inoue which you’ll find at the end of exhibition.

You’ll find art from the original of Tekkonkinkreet manga by Taiyo Matsumoto and Miss Hokusai by Hinako Sugiura. Takahiko Inoue’s basketball Slam Dunk is honoured with some especially dynamic artwork, beside Inoue’s more recent REAL, about disabled players. The REAL characters are also the subject of a specially-drawn triptych by Inoue which you’ll find at the end of exhibition.

For a breather, head to the “library” section in the middle of the space to leaf through a good range of titles, including 36 volumes of Ranma 1/2, nine books of Princess Jellyfish, and Tezuka’s original Metropolis strip… or you can download manga extracts straight onto your phone.

Then you can strike out again into less familiar waters. You can learn about sports legends like Tomorrow’s Joe (boxing) and Captain Tsubaba (soccer); about the original 1960s version of Cyborg 009, ancestor of Robocop; and about The Poem of Wind and Trees, the pioneering schoolboys-in-love-for-girls manga by Keiko Takemiya. There’s Golgo 13, the world’s greatest pro murderer created by Takao Saito; SF classics like Leiji Matsumoto’s Galaxy Express 999 and Takemiya’s Toward the Terra; the dark mystery manga of Daijiro Morohoshi; and the utter silliness of gag-meister Fujio Akatsuka (Osomatsu-kun).

There are still plenty of missing manga titans. Well, I think there are, though frankly there are so many displays round umpteen corners that it’s possible I missed some. Prowling the exhibit, I didn’t find Lupin, or Rose of Versailles, or any creations of Go Nagai. Akira seems to be missing, too, though there are images from other Otomo strips. I don’t think I found any Doraemon, which surely many Japanese visitors would find unforgiveable. But any normal visitor will be too busy processing the names which are there to register the omissions till later.

The later displays run off into manga-related areas, such as sections on anime-style information notices (murderer Golgo pops up again, presenting business security guidelines!). Cosplay gets a corner, and there’s a great video section displaying the madness of Comiket, the twice-yearly fanzine fair in Tokyo. Having been to Comiket, I was amused at how the display dodged any mention of the lashings of porn sold there… and for anyone wondering if this exhibition has a curtained-off “Adult” area, think again. The controversies about sexually explicit manga are restricted to a passing mention in the text; this is a (reasonably) family-friendly event.

The later displays run off into manga-related areas, such as sections on anime-style information notices (murderer Golgo pops up again, presenting business security guidelines!). Cosplay gets a corner, and there’s a great video section displaying the madness of Comiket, the twice-yearly fanzine fair in Tokyo. Having been to Comiket, I was amused at how the display dodged any mention of the lashings of porn sold there… and for anyone wondering if this exhibition has a curtained-off “Adult” area, think again. The controversies about sexually explicit manga are restricted to a passing mention in the text; this is a (reasonably) family-friendly event.

Staying in a family vein, I’m dubious about one large video display near the end of the exhibition devoted not to manga, but to the anime films of Studio Ghibli, showing extracts from all its films, and real footage from the studio. Compared with many other anime studios, Ghibli has a tenuous relation to manga – fewer than half of its films are manga adaptations. A speech at the event preview claimed Ghibli was a “gateway” to manga for many foreigners, but I suspect Death Note or Dragon Ball are more important. Still, Ghibli is part of the wider “drawn” media mainstream in today’s Japan, as the kabuki curtain was fourteen decades back.

But I liked the Ghibli display because I like Ghibli, regardless of whether it really fits into a manga exhibition. Similarly, pretty much anyone should like the British Museum’s exhibition if they like manga – regardless of whether the exhibition “should” be in the British Museum to start with.

The Manga Exhibition runs until 26th August. To check availability and book a timeslot in advance, click here. Members of the British Museum go free. The standard adult price is £19.50 for over-18s. Students, disabled and unemployed visitors pay £16, with disabled assistants going free. Visitors aged between 16 and 18 also pay £16, while under-16s go free if accompanied by a paying adult. Holders of National Art Passes pay £9.75. There are talks and other events related to the exhibition; for details, see here.

Leave a Reply