Manga Mania 1993-2000

February 25, 2018 · 6 comments

by Chris Perkins.

Not so long ago on this very blog, we recounted the history of Anime UK/FX –the UK’s first dedicated anime and manga magazine. It was soon joined on British newsstands by a rival named Manga Mania. This scrappy upstart would ultimately outlast its only competitor, and go on to run for some eight years, across three publishers and under several different editors.

Not so long ago on this very blog, we recounted the history of Anime UK/FX –the UK’s first dedicated anime and manga magazine. It was soon joined on British newsstands by a rival named Manga Mania. This scrappy upstart would ultimately outlast its only competitor, and go on to run for some eight years, across three publishers and under several different editors.

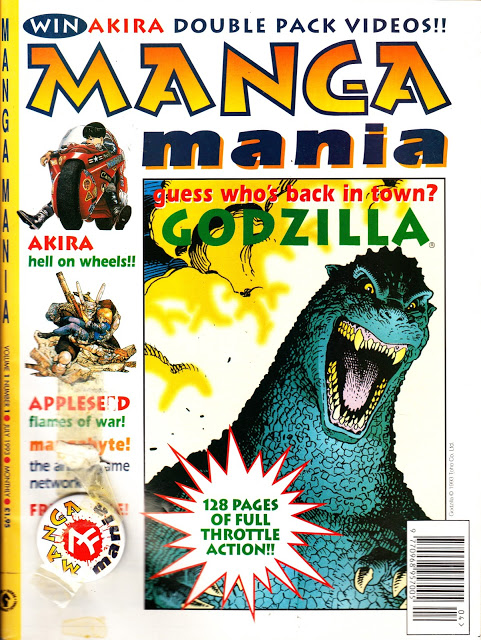

In its original form, the magazine was the UK’s first manga anthology. Although it also featured anime and manga news, features and reviews, the majority of each issue was taken up by serialised comics. Manga Mania was launched by the UK arm of Dark Horse Comics in 1993, under founding editor Cefn Ridout, who had been working on a number of licensed tie-in titles like Aliens, Star Wars and Jurassic Park.

“I’d recently returned from Japan,” he recalls, “where I was bowled over by the oversized manga anthologies, and felt that some kind of fusion between those and what DHI was doing could work in the UK. Especially as our US parent company had hooked up with Toren Smith’s Studio Proteus to translate, reprint and publish manga for the US direct market. At the time, there was also growing interest in anime in the UK in the wake of Akira’s popularity. Manga [Entertainment] and Kiseki [Films], were promoting and distributing anime videos while anime movies and TV series pulled in the crowds at conventions.”

Ridout saw the potential in launching a title aimed at this new audience and luckily the higher-ups at Dark Horse agreed. “Our first coup was landing the rights to publish the Akira manga, using Marvel’s translation and printing film, which became the backbone of Manga Mania.” Katsuhiro Otomo’s dystopian epic went on to become the magazine’s killer app and ran from the first issue until its completion in issue 37.

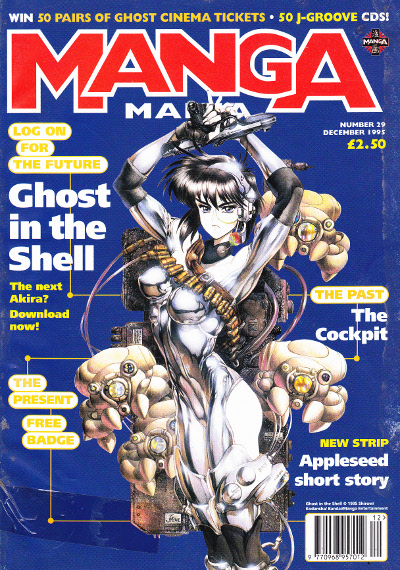

At the time, collecting manga in the UK generally meant shelling out for expensive, flopped US Import editions from your local comic shop (if you were even lucky enough to have a local that carried it). As such, £2.50 a month for more than 100 pages of manga was a godsend for fans. A number of other manga were serialised alongside Akira over the years, mostly reproductions of material already available in the USA such as Appleseed, Ghost in the Shell, Gunsmith Cats, 3×3 Eyes, and Silent Möbius. But Manga Mania also featured the English-language debut of Monkey Punch’s Shin Lupin III manga, some years before Tokyo Pop’s version.

At the time, collecting manga in the UK generally meant shelling out for expensive, flopped US Import editions from your local comic shop (if you were even lucky enough to have a local that carried it). As such, £2.50 a month for more than 100 pages of manga was a godsend for fans. A number of other manga were serialised alongside Akira over the years, mostly reproductions of material already available in the USA such as Appleseed, Ghost in the Shell, Gunsmith Cats, 3×3 Eyes, and Silent Möbius. But Manga Mania also featured the English-language debut of Monkey Punch’s Shin Lupin III manga, some years before Tokyo Pop’s version.

“Given the depth and diversity of manga we could choose from, I’d always envisaged publishing a variety of genres,” confesses Ridout, “but as most readers’ tastes ran to science fiction and fantasy that invariably skewed our selection process.” He fondly remembers Woodrow Phoenix’s ever-oblique and entertaining Sumo Family one-pagers, although their distinctive style (and non-Japanese origin) meant that much of the readership did perhaps not share his enthusiasm.

Ridout even looked into launching a companion title featuring manga aimed at a younger audience, with Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball Z intended to be the main event. Unfortunately, Toriyama refused to have his manga flopped for western publication, so it was never to be.

Barely a year after the first issue was published, Dark Horse pulled out of the UK market. Manga Entertainment swooped in, acquiring Dark Horse International’s portfolio as a means to launch a ready-made publishing arm of its own.

“Andy Frain and Mike Preece, Manga Entertainment’s [then] head honchos, had a strong vested interest in making Manga Mania work,” remembers Ridout. “It was far closer to their core business than it was to Dark Horse’s. And contrary to popular misconception, they never tried to influence what manga we published, or which anime we covered or how they were reviewed. It may be hard to believe in these more jaded, conspiratorial times, but it really was a mutually beneficial relationship.”

Akira, however, was such a part of the magazine’s identity that its ending created an identity crisis. Issue 38 saw what could perhaps be thought of as the magazine’s awkward adolescence. “With sales slowly declining, we relaunched with a half-hearted (and half-baked) attempt to attract the Loaded audience, which with hindsight was obviously misguided,” says Ridout. Attempting to reach a wider audience, it featured not only more Asian live-action cinema, but also unrelated western movies, comics and games. These issues even dumped the anime and manga covers for photos featuring glamorous Asian cover girls.

Not long afterwards Manga Entertainment pulled out of publishing altogether, selling the entire subsidiary to Titan. In 1997, it re-emerged closer to its original form, this time under the editorship of Helen McCarthy, whose own Anime FX had folded a year earlier.

“I was a bit shell-shocked, to be honest,” remembers McCarthy, “and probably trying to replace what I’d lost, but Manga Mania was a different magazine and Titan was a different setup. It was helpful to have that experience and know that you never go back.”

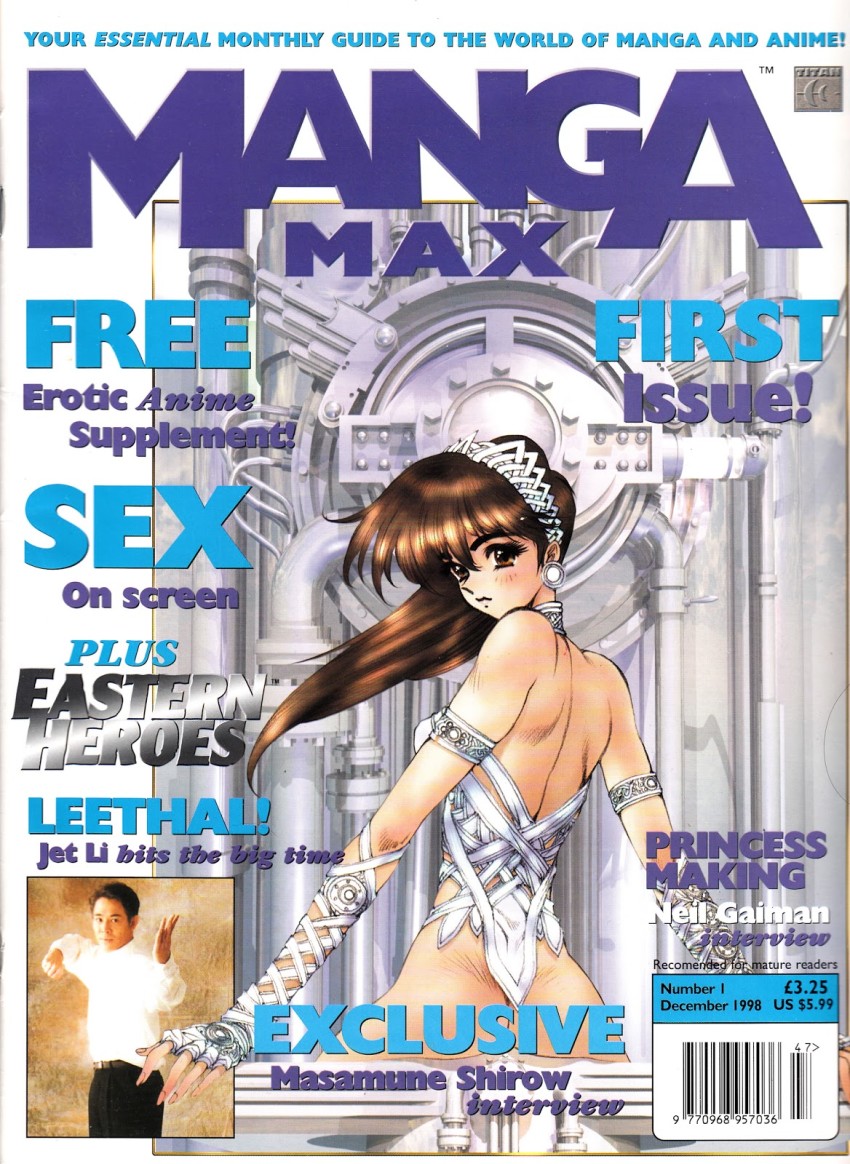

Production delays meant that there were often large gaps between issues, and just six issues made it onto the shelves over the course of 18 months. Titan relaunched the magazine yet again in 1998, in a new format as Manga Max, with new editor Jonathan Clements. “I’d been writing and translating for the magazine under Cefn, and sub-editing for Helen during her tenure,” Clements recalls. “Both of them, it later turned out, had recommended me on their way out the door, but Titan took their sweet time offering me the job. Years later, I got to see the personnel report on my interview, which read: ‘Have reservations about his attitude, but definitely knows his stuff.’ That will probably be on my tombstone.” It was a big step-up in production quality, now an oversized, glossy full-colour title. The UK’s anime industry was not at its peak at this time, and MM reacted by having a more international focus. Much of the coverage and reviews were now given over to US releases.

Production delays meant that there were often large gaps between issues, and just six issues made it onto the shelves over the course of 18 months. Titan relaunched the magazine yet again in 1998, in a new format as Manga Max, with new editor Jonathan Clements. “I’d been writing and translating for the magazine under Cefn, and sub-editing for Helen during her tenure,” Clements recalls. “Both of them, it later turned out, had recommended me on their way out the door, but Titan took their sweet time offering me the job. Years later, I got to see the personnel report on my interview, which read: ‘Have reservations about his attitude, but definitely knows his stuff.’ That will probably be on my tombstone.” It was a big step-up in production quality, now an oversized, glossy full-colour title. The UK’s anime industry was not at its peak at this time, and MM reacted by having a more international focus. Much of the coverage and reviews were now given over to US releases.

“Titan wanted it to serve the entire English-speaking world, so I was encouraged to run articles on things when they appeared in the US or UK,” says Clements. “Unfortunately, this directive came at the end of the period when the UK led the US market in any appreciable way, so it ended up pleasing nobody, with articles about products that many readers stood little chance of affordably (or legally) obtaining.” Conversely, for readers outside the UK, lengthy shipping times meant that by the time the magazine had made its way to the US or Australia, the information inside was months out of date.

The key difference was that Manga Max dropped the serialised manga entirely. “We’d run out of Akira, which was the real motherlode,” explains Clements. “Cramming it with other comics was likely to be an expense, rather than a cost-saving venture. There was talk in initial meetings of running previews of new manga that Titan hoped to get for free. I said that was sure to be an approvals and negotiation nightmare with the Japanese, and I wanted nothing to do with it.” The magazine instead consisted of news, features reviews and columns covering anime and manga, and a smattering of other Japanese and Asian Pop Culture.

“I wanted to hold anime to a higher standard, to write about it in the way that the mainstream press would write about it if we were in an alternative universe where they cared.” Clements says. “I wanted to give people the tools and the vocabulary to talk about anime in a smart way. In a very real sense, that was a deliberate continuation of the project Helen had started with Anime UK.”

Manga Max’s final issue was published in 2000. The latter issues predicted a new era of anime fandom would be born out of the success of Pokémon and Studio Ghibli, but sadly the magazine ceased publishing before it could see the boom happen.

Titan briefly flirted with bringing it back, going as far as producing a Manga Max branded insert with a 2006 issue of DreamWatch, the science-fiction magazine, although Clements was not involved. Although as he remembers: “There were staffers at Titan assuring a lot of anime distributors that I was!” Instead, editorship on this last iteration of the magazine was credited to Andrew Osmond, the future author of 100 Animated Feature Films.

Nonetheless, Manga Mania/Manga Max lasted an impressive number of years throughout what were often turbulent times for the UK industry. It served fans hungry for more anime and manga and influenced many of its readers, including Gareth Evans, future director of The Raid and, well, me.

What was the secret of its success? “Right place, right time… at least for a while,” suggests Ridout. “We all rode the Akira wave for as long as possible until other tent-pole anime like Ghost in the Shell and Evangelion came along to lift the market out of its periodic slumps. I also feel, unsurprisingly, that the overall quality of MM’s contents – manga and editorial – and keeping costs down, played a significant part in our relative longevity. But credit also goes to people behind the scenes like Liliana Bolton, Dark Horse UK’s MD, and Dick Hansom, Manga Publishing’s Editorial Director, whose unwavering support for Manga Mania was instrumental to its existence and survival.”

There would have been no Manga Max without Manga Mania, and there would have been no Mania without the hard work of Cefn Ridout. What was his favourite thing about his time at the helm? “Developing and publishing a magazine that I’d want to read, which covered Japanese/Asian pop culture alongside some of the best manga being published at the time – what’s not to like? Plus we eventually translated and published new manga in the magazine and Manga Publishing’s graphic novel line, which was my ultimate goal.”

“Moreover, I had the opportunity to work with a bunch of talented, expert and like-minded folk such as Toren Smith, Fred Schodt, Jonathan Clements, Trish Ledoux, Julie Davis… the list would go on forever, so my apologies to anyone I’ve missed.”

Throughout the best part of a decade, Manga Mania/Manga Max played a key part in the history of anime and manga in the UK that deserves to be recognised. It may now be long gone, but its legacy is still felt to this day.

Chris Perkins writes about anime for MyM magazine and is the editor of Animation For Adults.

rob brindlow

January 28, 2020 9:14 am

does anyone remember the striker (spriggan) comic that ran after Akira finished?

Seth Dark

September 13, 2021 9:28 pm

Yep, I do remember Striker. Still got the Manga Mania issues but in a box, and what condition... I do not know.

Seth Dark

September 13, 2021 9:32 pm

I do.

Kelly

November 10, 2021 2:11 pm

How much is the first edition of Manga Mania worth?!

David Parsons

November 12, 2021 10:47 am

I still have most of my copies, even the first.

JJ Doom

May 23, 2023 9:55 am

There was a review of an art book in one issue. Always remember the ‘why Hello Kitty has no mouth.’ Always kept up to date with manga video releases. Still have the pin badge somewhere.