Millennium Actress & Japanese Film

December 28, 2020 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Millennium Actress comes loaded to the brim with references to Japanese film, although many of them, perhaps for legal reasons, have been tweaked a little so as not to be blatant hommages. So it is that we see leading lady Chiyoko with a robotic lizard, evocative of the iconic Godzilla, but not actionably similar to him. A moment on castle battlements finds Chiyoko attired and made up in imitation of Lady Kaede (Mieko Harada) from Akira Kurosawa’s Ran (1985), looking down on a scene of samurai combat similarly suggestive of that film. And yet, in the same sequence, the cameraman Kyoji is pinned to the wall by a volley of arrows, in clear reference to another Kurosawa classic, Throne of Blood (1957). There are nods in Millennium Actress to Yojimbo (1961) and Seven Samurai (1954), but also to movies less well-known outside Japan, such as 24 Eyes (1954), the story of a schoolteacher who gets to look in at her pupils at different point in their educational lives – in 1954, the year that Seven Samurai took overseas awards by storm, it was 24 Eyes that garnered the most critical praise in Japan.

If such moments prompt the viewer to feel like an outsider at cocktail party, missing the point of in-joke after in-joke, we might remember that even the director Satoshi Kon regarded himself as a relative novice to the joys of movie history. ““I am not really familiar with Japanese films,” he commented in an interview at the time of the film’s release. “I think I get more from the combination of memorable films that I saw in my childhood, rather than particular scenes from particular films.” In other words, much as Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s Ninja Scroll (1993) deliberately sought to evoke the feeling of Japan’s ninja canon rather than specifically adapting the works of Futaro Yamada or Sanpei Shirato, Kon’s movie references are a set of impressions of certain movie types – a fantasy of what the films might have been, rather than what they actually were.

Chiyoko, too, is a composite character, combining elements of several real-world movie stars of yesteryear. Yoshiko “Shirley” Yamaguchi (1920–2014), for example, was the forces’ sweetheart of wartime Manchuria, a Japanese girl who had grown up in the occupied territory and spoke perfect Chinese. Masquerading as a Chinese actress, “Li Xianglan”, she appeared in more than a dozen films of the period, many of them unknown to modern audiences, although certain songs associated with them remain karaoke staples in both China and Japan. However, Chiyoko owes far more to Setsuko Hara (1920–2015), the actress who was a muse for Yasujiro Ozu in such films as Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953), before withdrawing from the public eye after Ozu’s death in 1963. Known in the Japanese media as “the Eternal Virgin,” the retired Hara lived as a recluse for decades, refusing all approaches from the media. Another candidate for Chiyoko’s inspiration can be found in Hideko Takamine (1924–2010), whose acting career spanned five decades from her first appearance onscreen as a child; she often appeared in the films of Mikio Naruse, but would marry another director, Zenzo Matsuyama in the 1950s.

As the film moves into a shaky-cam rendition of scrappy 1960s swordplay movies, Genya comes to Chiyoko’s rescue in a pastiche of The Tale of Zatoichi (1962). She asks why he keeps breaking into her story, and he says that he is following her just as she is following the trail of the man who gave her the key. “But I am in love with him,” she replies, and Genya is suddenly tongue-tied. Her adoration of a man she does not know is an almost religious affectation that, she has decided, brings meaning to her life. It is implied that Genya’s fannish love of Chiyoko is something similar for him.

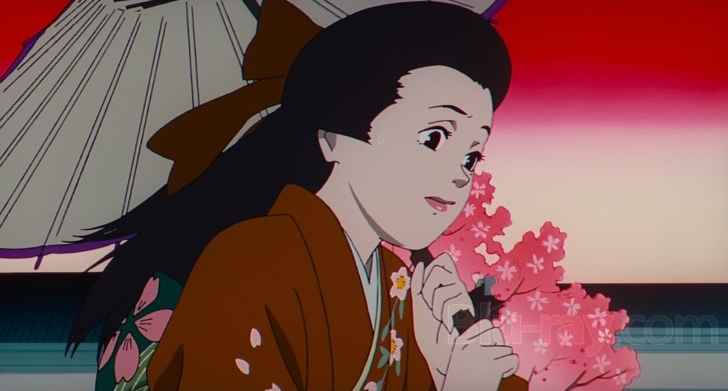

Chiyoko runs for Kyoto, where she trips and falls into yet another film. She loses her footing in the middle of a ninja movie, but hits the ground in a geisha melodrama. She is arguing with the same woman, but instead of shadow warriors, they are bedecked in the finery of samurai-era courtesans, and Chiyoko’s nemesis Eiko has suddenly acquired a Kyoto accent.

Kon’s favourite scene in his own film is the one in which Chiyoko travels through multiple time periods. She clambers aboard a horse to escape Shinsengumi vigilantes in the 1860s, before riding through a sequence from the Boshin War, of 1868–9, in which the last loyalists to the Shogun were pushed out by the restorationists fighting in the name of the Emperor Meiji. Consequently, it is depicted in the colours of the era’s dominant medium, the ukiyo-e woodblock print, from which organic dyes have faded to leave a palette predominant with blues. But as Chiyoko’s mode of transport changes to a horse and carriage, and her dress becomes more European, the colouring of the sequence suddenly takes on bright slashes of red, in recognition of the aka-e (“red pictures”) of late 19th century – still woodblocks, but coloured using vibrant pigments newly arrived from the west. The carriage wheels gain rubber tyres, and suddenly Chiyoko is in a rickshaw, but even as we realise this, she is being overtaken by Kyoji and his camera, piggy-backing on a military automobile. Now she is on a bicycle, free-wheeling downhill, for the first time without the agency of a beast of burden or male companion, until she comes to a screeching halt, facing her pursuer, the man with a scar once more. He is now a military police enforcer, and his interrogation of her takes place in an avenue blazing with cherry blossoms, the symbol of sacrifices to come.

This where we came in. Chiyoko, the character, has now caught up in time periods with Chiyoko, the actress, arriving in the 1930s when her real-world self begins her acting career. Of course, this can only add to the confusion, since now it is even harder to spot where the dividing line is between Chiyoko’s memory of her life and her roles.

Another moment in the film alludes to What is Your Name? (1952–54) a radio series that was rebooted into a trilogy of cinema features, about a couple who meet during the Great Tokyo Air Raid and swear to come back to the same spot six months or a year later. Fates intervene, and by the time they are reunited, they have acquired new lives and new responsibilities. The story was a national obsession in 1950s Japan, although its long-term heritage, particularly in online search engines, has been wiped out by Makoto Shinkai’s similarly titled anime of 2016. Here, however, in Millennium Actress, we see Chiyoko’s story dovetailing with this 1950s classic, both in terms of her quest to be reunited with a missing man, and with the distinctive head-wrap she is seen wearing while doing so.

“Is this sci-fi?” wonders Kyoji, as Chiyoko gazes out over a red-tinged, apocalyptic vista. But no, this is not sci-fi. This is Tokyo under an endless rain of American bombs. And when Chiyoko, seemingly the real Chiyoko in this memory, collapses at the sight of a picture of her younger starlet self in the ruins, we are jolted back to the present by the realisation that while the memory may be real, the collapse has happened to the older Chiyoko, who has been concealing her debilitating illness from her interviewer.

“Come back another day,” she warns, “and I may not remember anything.” It is another clue that her grasp on the truth is already compromised.

As the film enters its second half, an increasing number of scenes at first appear to replay actual events from Chiyoko’s life. The seductive attentions of the director Otaki, for example, are played naturalistically, as is a moment of supreme irony, when Chiyoko is shoved aside on a Tokyo street by an inattentive passer-by, right in front of a film poster that announces that she is the “Madonna of Tokyo.”

Another sharp shock of reality is brought by Chiyoko’s mother, who also alludes to “madonnas”, but here in the sense of the unattainable leading ladies in the long-running Tora-san film series. Chiyoko’s screen persona, argues her mother, is transient and ephemeral – she needs to find herself a husband before her movie glamour evaporates. But this, too, suddenly cuts into a scene from a movie set.

Chiyoko confronts her rival Eiko over the theft of a keepsake key, but now we are in a theatre, with the home that Chiyoko shares with her husband revealed as just another set. Did Chiyoko ever confront Eiko? And if not, how can we even know that it was Eiko who stole it? Eiko’s entire confession, that she has been manipulating Chiyoko’s obsession with her lost love for twenty years or more, ever since a trip to a Manchurian fortune teller, is hence just as doubtful as everything else. For the Japanese film-lover, this sequence also seems redolent of Kon Ichikawa’s Film Actress (1987), which fictionalised the life of the Japanese movie star Kinuyo Tanaka (1909–77), including her disastrous marriage to an industry colleague.

For over an hour, Chiyoko has been chasing her nameless, phantom lover through time, cherishing a seemingly pointless McGuffin – a key that opens nothing. But there are enough clues in the framing sequences, regarding the aged Chiyoko’s illness, to suggest that literally everything is a fuzzy, confused dreamscape, mixing half-remembered real events with false memories born of rehearsals and multiple takes in old movies. Chiyoko will claim, towards the film’s end, that the key has “unlocked” her fading memories one final time, but if it has truly allowed her to look back on her life, to steal a movie metaphor, its focus is blurry and indistinct. Although Genya mentions that Chiyoko did indeed run away to Hokkaido at one point, we cannot possibly be expected to seriously believe that the name of her train coincidentally evoked her phantom lover’s description of painting the starry sky and cold snow-scape, nor that she would really run into the road to be greeted by the unmistakeably garish grille of a highly decorated lorry. It is being driven by Genya, and Kyoji archly announces that this, at last, is a role Genya was born to play.

Spanning the years 1975 to 1979 and inspired by the American TV show Route 66, the Truck Guys films were the Toei studio’s blue-collar answer to Shochiku’s Tora-san, and starred Bunta Sugawara and Kinya Aikawa as a pair of good-hearted big-rig drivers, righting wrongs all over Japan. Cranked out at two a year by the Toei studio, Truck Guys kept to a recurring tragi-comic formula, in which Sugawara would roll into a new town, fall in love with a “Madonna” figure played by the actress-of-the-moment, and find himself having to unite her with her true love, putting his own feelings aside. Kyoji’s comment is hence both an acknowledgement of Genya’s own hopeless infatuation with Chiyoko, and also that the film’s movie hommages have now entered the 1970s. Of the many allusions in Millennium Actress, this may be one of the most likely to pass Western viewers by.

Then again, Kon himself would observe, possibly as a result of the response to Millennium Actress, that he no longer expected even Japanese audiences to spot movie allusions. Referring to a scene in his later Paprika, in which a character appears wearing clothes that evoke the on-set attire of famous director Akira Kurosawa, Kon admitted that he thought more people outside Japan would spot the gag. “Young anime fans of Japan,” he declared, “probably wouldn’t recognise him at all.”

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Millennium Actress is released on UK Blu-ray by Anime Limited.

Leave a Reply