Millennium Actress

February 12, 2020 · 1 comment

By Jasper Sharp.

Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress uses its heroine to explore themes of subjectivity and spectatorship, with a topic that might at first seem better suited to live action. In all those elements, it bears some similarities with his debut feature Perfect Blue (1997), which pitched the viewer into the fragmenting worldview of a retired teen pop idol, haunted by her former stage persona. Both films played with audience expectations as to what was permissible or appropriate within the medium, while blurring the boundaries between the illusory and the real through a labyrinthine series of flashbacks, shifting character perspectives, films within films and dream sequences. The crucial difference with Millennium Actress, however, is its marked lightness of tone.

Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress uses its heroine to explore themes of subjectivity and spectatorship, with a topic that might at first seem better suited to live action. In all those elements, it bears some similarities with his debut feature Perfect Blue (1997), which pitched the viewer into the fragmenting worldview of a retired teen pop idol, haunted by her former stage persona. Both films played with audience expectations as to what was permissible or appropriate within the medium, while blurring the boundaries between the illusory and the real through a labyrinthine series of flashbacks, shifting character perspectives, films within films and dream sequences. The crucial difference with Millennium Actress, however, is its marked lightness of tone.

As Kon told Tom Mes in a 2002 interview for Midnight Eye, “Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress are two sides of the same coin, I think. When I was making Perfect Blue I thought it would be a positive film, but little by little it became negative, darker… I had the intention of making the two films like sisters, through the depiction of the relationship between admirer and idol. So in adapting that relationship I wanted to make Millennium Actress in completely opposite, more positive images.”

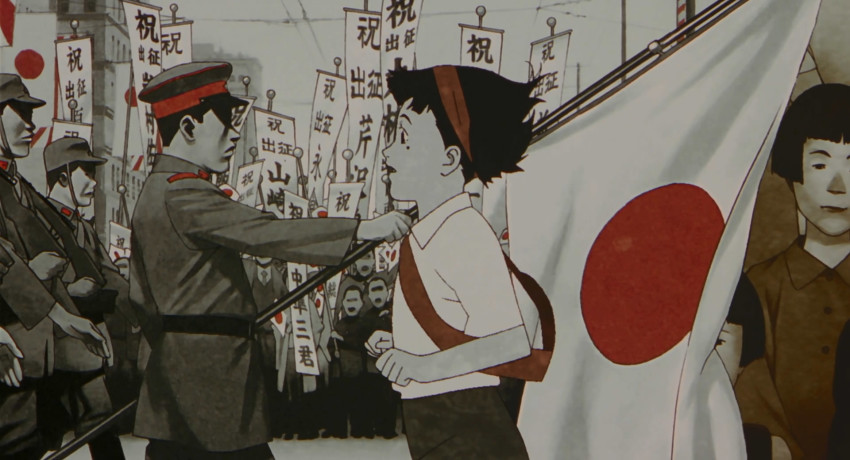

The idol in this case is the enigmatic and reclusive Chiyoko Fujiwara, a legendary film star of yesteryear. The admirer is a middle-aged documentary-maker, Genya, who is granted a rare interview to mark the demolition of the Gin’ei Studios where she made her greatest performances. Mediating this encounter is his cameraman, Kyoji, a man clearly not quite as smitten with his subject. Nevertheless, after giving Chiyoko an ornate key they have discovered in the bulldozed studio’s rubble, both men find themselves swept away in the vivid stream of memories it unlocks, as Chiyoko leads them on a journey through her past lives and loves, both onscreen and off, from the pre-war beginnings of her career through the classical era of 1950s period dramas and beyond.

Both Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress were co-scripted by Kon and Sadayuki Murai. While the first film is very much set in the here and now, this second tracks its subject over the course of her life, from girlhood to old age, playing an unreliable narrator and the way in which we make fictionalised narratives of our own lives by elevating certain memories, suppressing or rejecting others, and even creating a few along the way. As Kon explained to Mes, “for Perfect Blue, in the beginning there was a story and to tell that story we applied this method. Whereas with Millennium Actress, the method itself is the aim of the film.”

Both Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress were co-scripted by Kon and Sadayuki Murai. While the first film is very much set in the here and now, this second tracks its subject over the course of her life, from girlhood to old age, playing an unreliable narrator and the way in which we make fictionalised narratives of our own lives by elevating certain memories, suppressing or rejecting others, and even creating a few along the way. As Kon explained to Mes, “for Perfect Blue, in the beginning there was a story and to tell that story we applied this method. Whereas with Millennium Actress, the method itself is the aim of the film.”

As Kon visually translates Chiyoko’s story as it is delivered for Genya’s film, we are left asking if the images we are presented with are based on events that she experienced in reality, or on a film set, or onscreen somewhere while acting out someone else’s fantasies, or maybe from misremembered scenes from her films, and where exactly is the dividing line between Chiyoko the person and Chiyoko the actress.

There are many ways one can read Millennium Actress. We might see it as a celebration of film and animation’s magical ability to make our fantasies seem real. The hyper-realistic “life-like” style of Kon’s team at Madhouse Studio is applied to a story that celebrates Japan’s cinematic heritage, but also draws attention to the fact that little separates animation and live-action when it comes to sweeping the audience up in spectacle and storytelling.

One thing Kon, whose all-to-brief directing career was tragically cut short by pancreatic cancer in 2010 at the age of 46, never intended Millennium Actress to be, however, is a historical guide to Japanese cinema, its real-life stars, or their stories. In his book Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, Andrew Osmond cites the director as confessing, “I am not really familiar with Japanese films. I think I get more from the combination of memorable films that I saw in my childhood, rather than particular scenes from particular films.”

Nevertheless, Chiyoko Fujiwara’s fictional career trajectory does bear similarities with certain iconic figures from Japanese cinema’s Golden Age. The most obvious is Setsuko Hara, whose most celebrated roles as dutiful unwedded daughters, widowed step-daughters or maiden aunts in the home dramas of Yasujiro Ozu such as Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953) earned her the unflattering label of the “eternal virgin”. Shortly after Ozu’s death in 1963, Hara suddenly announced her retirement from acting and spent the rest of her life as a recluse in Kamakura, refusing to grant any interviews until her death in 2015. She never married, although there were rumours of an off-screen romance with Ozu, who also lived the same city close to the studio facilities of Shochiku. Shochiku’s Ofuna studios were closed in 1998, an event clearly referenced by the demolition of the Gin’ei studios in Millennium Actress.

Nevertheless, Chiyoko Fujiwara’s fictional career trajectory does bear similarities with certain iconic figures from Japanese cinema’s Golden Age. The most obvious is Setsuko Hara, whose most celebrated roles as dutiful unwedded daughters, widowed step-daughters or maiden aunts in the home dramas of Yasujiro Ozu such as Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953) earned her the unflattering label of the “eternal virgin”. Shortly after Ozu’s death in 1963, Hara suddenly announced her retirement from acting and spent the rest of her life as a recluse in Kamakura, refusing to grant any interviews until her death in 2015. She never married, although there were rumours of an off-screen romance with Ozu, who also lived the same city close to the studio facilities of Shochiku. Shochiku’s Ofuna studios were closed in 1998, an event clearly referenced by the demolition of the Gin’ei studios in Millennium Actress.

Hara was born in June 1920, just a few years prior to the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 during which Chiyoko’s character was meant to have been born and her father killed. Hara’s years of activity as a film actress, from 1935 to 1963, cover a similar timespan to Chiyoko’s, although she had left the industry before some of the franchises references in Millennium Actress. Although Kon’s film alludes to both the blind-warrior Zatoichi series and the Truck Guy road movies, the real-world Hara never appeared in either, nor did she ever appear in a science fiction film.

However, there are some parallels in Chiyoko’s decision to launch her film career by heading to Manchuria, Japan’s 1930s Chinese-based puppet state. Hara’s career boost came with the Daughter of the Samurai (1936), a misguided co-production that attempted to find common cultural ground between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Although shot largely on the Japanese mainland, the film concluded with her character moving to Manchuria.

The Manchurian connection brings to mind another Japanese actress born in 1920, some elements of whom appear to have been incorporated into Chiyoko. Yoshiko Yamaguchi was born in Manchuria to Japanese parents, but was hoisted to stardom by the Man’ei film company, established by the Japanese in 1937. For almost a decade she was promoted, under the name of Ri Koran, as a genuine Chinese actress and as an ambassador of goodwill sympathetic to Imperial Japan. It was enough to almost get her executed by the Chinese at the end of war – only her Japanese passport saved her from being shot as a traitor. She subsequently appeared under her own name for directors including Akira Kurosawa, as well as playing under another guise, appearing as Shirley Yamaguchi in Samuel Fuller’s House of Bamboo (1955), the first American feature shot on location in Japan in the post-war era. She also featured in the live-action White Snake Legend (1956) – the later animated version, Hakujaden (1958) was anime’s first full-length movie, and featured a female lead strongly modelled on Yamaguchi’s facial features. In the late 1950s, she married a diplomat and retired from the screen, later entering a new life in politics.

Like Hara and Yamaguchi, and we can say the same of performers of any era, if the “real” Chiyoko and her emotional world remain perplexing and mysterious, it is because she is ultimately a product of the constructions and projections of both filmmakers and audiences alike, the subject of a multitude of narrative possibilities. She is a mirage at the heart of an industry whose very basis is in the trading of illusions.

Jasper Sharp is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

Millennium Actress is being released as a 4K UHD + Blu-ray Collector’s Edition set by Anime Limited.

anime, Japan, Jasper Sharp, Millennium Actress, Perfect Blue, Sadayuki Murai, Satoshi Kon

Thijs

February 13, 2020 6:23 pm

Here's hoping for a blu-ray release.